Times they're a changin: Why Army should be a less manpower-intensive force

The Army is also drawing lessons from the navy, which kept its numbers at just 71,600, and consequently has 46 per cent of its budget available for equipment

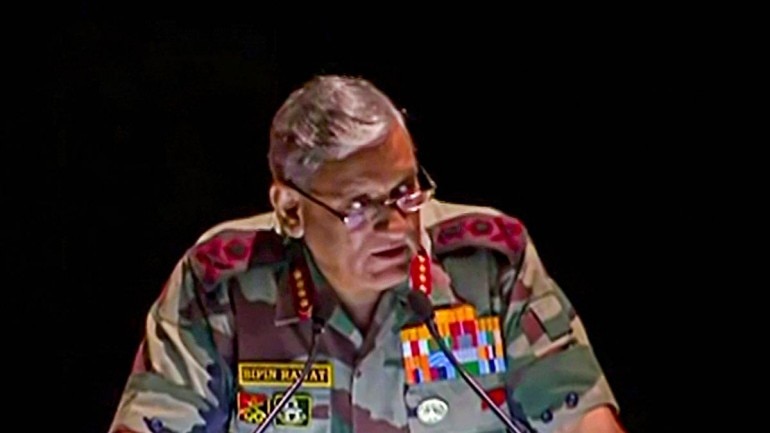

Army chief General

Bipin Rawat brainstormed with his top generals in Delhi this week, seeking a consensus on reforms to make the Army a less manpower-intensive force.

It is learnt that most commanders are on board with what one described, “The Army’s most ambitious reforms attempt since Independence.”

India’s military has not changed radically since 1947, despite two waves of reforms. The first followed the 1962 defeat at the hands of China and involved raising mountain divisions for the Himalayan frontier. Then, in the 1980s, two thinking Army chiefs — Generals KV Krishna Rao and K Sundarji — initiated a mechanisation of the Army that led to the creation of three armour-heavy strike corps. Even so, the Army’s combat force — infantry battalions, armoured regiments and artillery regiments — remain almost identical today to what it was during the Second World War.

The current drive for change stems from a recognition of the need to slash the Army’s numbers. These have defied global trend of force downsizing to rise from under a million two decades ago to 1.22 million today, according to figures tabled in December in Parliament. Consequently, the Army’s budget for new equipment is just Rs 267 billion ($3.73 billion), while over four-fifths of its Rs 1.55 trillion ($21.6 billion) allocation goes on running expenses, primarily salaries and pensions.

This alarming situation has arisen from decades of “empire building”, where successive Army chiefs have sought to expand their fiefdoms, making the Army ever larger and creating more general rank vacancies. A decade ago, the Army only allowed new roads along the Sino-Indian border in Arunachal Pradesh. Two new mountain divisions were sanctioned to defend these new approaches into India. That added 50,000 soldiers to the already bloated army. Then the generals successfully pushed for a new mountain strike corps, which is currently being raised and will add 60-70,000 soldiers. Only now has the Army realised it can either pay and feed this multitude, or equip them with modern weaponry.

The Army is also drawing lessons from the navy, which kept its numbers at just 71,600, and consequently has 46 per cent of its budget available for equipment. The Air Force, with 142,500 airmen, spends a healthy 49 per cent on equipment.

Another example of manpower reforms is presented by China, where the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has cut back on well over a million soldiers in order to pay for a western style military, equipped with the weaponry for a modern, high-tech war. In the latest wave of manpower cuts that President Xi Jinping ordered in September 2015, the PLA reduced its size by 300,000 persons.

The Indian Army, however, has traditionally chosen the easy, incremental path, rather than radical surgery. An internal organisation called the Army Standing Establishment Committee (ASEC) periodically reviews the manpower of units and formations, evaluating authorisations and quizzing units about why their five authorised barbers cannot be reduced to four, or the authorisation of 1.5 drivers per vehicle cannot be reduced to 1.3 drivers. The ASEC has made significant cuts in logistic units, but treads softer with combat units, which enjoy the status of the Army’s cutting edge.

That is where Rawat’s initiative departs from tradition: it intends taking the knife to combat units as much as to the support and services elements. The first of the three committees that have already been constituted will scrutinise the field force — the combat units, brigades, divisions and corps that form the tip of the military spear. A second initiative will examine ways of paring down Army headquarters (AHQ), which is considered bloated and overstaffed. Separately, a third committee will examine the Army’s 49,500-strong officer cadre and consider how best to give the Army the best possible commanders.

“The Shekatkar Committee (in December 2016) recommended cutting down 57,000 Army employees, of which 27,000 are uniformed personnel and 30,000 civilians. Now, we are looking at cutting down another 50,000 personnel. The aim is to stabilise the strength of the Army at 10-11 lakh personnel,” Rawat told Business Standard.

Reorganisation of combat units

Practically guaranteeing resistance from within, Rawat has directed that flab cutting must include that holiest of holy cows, the infantry battalion. Since the Army has 450 infantry battalions (each with 22 officers and 850 soldiers) paring 25 men from each battalion would result in the reduction of 11,250 men.

Wisely, the Army chief has formulated an operational rationale for this reorganisation, which will be overseen by the Army’s “perspective planning” chief Lieutenant General Rajeshwar. An infantry battalion currently has four rifle companies, each with about 125 men. This is partly based on the logic that when the battalion is given a task, such as attacking an enemy position, it can attack with two companies, with the other two in reserve, in case added punch is needed. Now, it will be considered whether, instead of pessimistically catering for reinforcing both forward companies, it would be wiser to keep just one company in reserve, while adding to the probability of initial success by strengthening each company to 170 men. In the new proposals, a company would also be authorised a ghatak (commando) section of 14 soldiers for special tasks. For example, a company attacking a hill feature could send its ghatak section to lay an ambush to cut off the enemy’s withdrawal. With three strengthened companies, the infantry battalion’s bayonet strength would remain the same, but eliminating one company headquarters would save 25 men.

Infantry reorganisation would extend to the grassroots, with a 10-man infantry section being strengthened to 14 soldiers, thus empowering the section commander, normally a havaldar (sergeant). A platoon, with three strengthened sections, would go up from the current 36 soldiers to 50 men.

Another measure that Rajeshwar will consider is flattening the hierarchy of higher headquarters. Currently, the division, with about 18,000-20,000 soldiers, is the lowest formation that comprises all the elements needed for combat — infantry, armour, artillery, engineers, signals and logistics. In wartime, those elements are often decentralised to constitute a self-sufficient “brigade group” for independent missions. Extending that model of decentralisation to peacetime as well would eliminate numerous manpower-heavy division headquarters, placing the brigades directly under corps headquarters.

Naturally, a divisional headquarters would be useful for coordinating an operation that involves two or three brigades, such as a strike corps offensive, which requires several armoured brigades to operate in unison. Strike formations, therefore, might as well retain the divisional structure.

Reorganisation of AHQ

The Army’s chief of “financial planning”, Lieutenant General Ajai Singh, will propose ways of paring AHQ. One widely discussed measure is to merge AHQ’s Military Training Directorate with the Simla-based Army Training Command, which performs overlapping functions. Another is to move the Rashtriya Rifles HQ from New Delhi to Udhampur or Srinagar, where all Rashtriya Rifle battalions operate. This would follow the model of the Assam Rifles, whose directorate is based in Shillong, close to its area of responsibility.

Similarly, there is a directorate of information technology and another of information systems, both performing overlapping functions. Merging these is a possibility. There is similar duplication of cells that deals with information warfare: one such cell works for the Military Operations directorate and another for Military Intelligence.

Officer cadre restructuring

The general who manages the Army’s officer cadre — Military Secretary, Lt Gen JS Sandhu — is heading the third committee. He will examine whether the Army’s current officer shortfall of about 8,000 must be made up, or whether the overall authorisation can be reduced by about 5,000.

“Making up the full strength would make the competition for promotion even more intense than it already is. The percentage of officers approved for promotion in each board – already worryingly low – will fall even lower,” points out a senior general who briefed Business Standard on the rationale for reorganisation.

Instead, the Army will examine whether a larger number of meritorious soldiers and junior commissioned officers (JCOs) can be promoted from the ranks to fill up officer vacancies. There is also a proposal to recruit JCOs directly — currently a soldier serves about 15-18 years in the ranks before being promoted to JCO.

“A direct entry JCO can do one year of training at the Officers’ Training Academy at Gaya or Chennai. Both these are running at half capacity and one of them can easily be made over to training JCOs and soldiers who are selected for becoming officers,” says the senior general.

Another major issue is the age of commanding officers (COs). After the Kargil conflict, when the Army had found its 41-42 year-old COs struggling to operate at altitudes above 15,000 feet, it launched a successful drive to reduce the age of COs to about 37 years. But now, some COs, who assume command with just 15-16 years of service, have been found to be lacking in experience and maturity. Further, since the CO has to be the senior-most officer in the battalion, there is no space for superseded officers, who have often served 17-18 years. The committee will explore whether promotion to colonel can still be done at 15-16 years of service but then, before assuming command, these officers can serve a two-year tenure as a staff officer. That would develop their skills and experience, allow them to mature in service and also create the space within units for superseded officers.

While increasing the age of COs, the committee will examine options for reducing the age profile of higher commanders. Currently, because of late promotions to higher ranks, officers serve just three years each as brigadiers, major generals and lieutenant generals, commanding their brigades, divisions and corps for just 12-15 months. Now, like the Navy and Air Force, the Army will try and give senior officers five years in each of those ranks.

That, however, would require more officers to be superseded at the ranks of colonel, brigadier and major general. As an example, the Army has 14 corps commanders, each of them a lieutenant general. If 14 major generals are approved every year for promotion to lieutenant general, the serving corps commanders would have only a year in the saddle before the next batch is breathing down their neck. To increase command tenures, fewer officers would have to be approved for promotion, a deeply unpopular step.

Rawat shrugs off suggestions that he may have aimed too high. “I am definitely not the first chief to have attempted this. Such studies have been done since the days of General K Sundarji and General Bipin Joshi. However, we failed to implement those,” he said. It remains to be seen if reorganisation is an idea whose time has come