Oppression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang/China

- Thread starter johnq

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?

China Secretly Built A Vast New Infrastructure To Imprison Muslims

China rounded up so many Muslims in Xinjiang that there wasn’t enough space to hold them. Then the government started building.

Built To Last A BuzzFeed News investigation based on thousands of satellite images reveals a vast, growing infrastructure for long-term detention and incarceration.

China has secretly built scores of massive new prison and internment camps in the past three years, dramatically escalating its campaign against Muslim minorities even as it publicly claimed the detainees had all been set free. The construction of these purpose-built, high-security camps — some capable of housing tens of thousands of people — signals a radical shift away from the country’s previous makeshift use of public buildings, like schools and retirement homes, to a vast and permanent infrastructure for mass detention.

In the most extensive investigation of China’s internment camp system ever done using publicly available satellite images, coupled with dozens of interviews with former detainees, BuzzFeed News identified more than 260 structures built since 2017 and bearing the hallmarks of fortified detention compounds. There is at least one in nearly every county in the far-west region of Xinjiang. During that time, the investigation shows, China has established a sprawling system to detain and incarcerate hundreds of thousands of Uighurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities, in what is already the largest-scale detention of ethnic and religious minorities since World War II.

These forbidding facilities — including several built or significantly expanded within the last year — are part of the government’s unprecedented campaign of mass detention of more than a million people, which began in late 2016. That year Chen Quanguo, the region’s top official and Communist Party boss, whom the US recently sanctioned over human rights abuses, also put Muslim minorities — more than half the region’s population of about 25 million — under perpetual surveillance via facial recognition cameras, cellphone tracking, checkpoints, and heavy-handed human policing. They are also subject to many other abuses, ranging from sterilization to forced labor.

To detain thousands of people in short order, the government repurposed old schools and other buildings. Then, as the number of detainees swelled, in 2018 the government began building new facilities with far greater security measures and more permanent architectural features, such as heavy concrete walls and guard towers, the BuzzFeed News analysis shows. Prisons often take years to build, but some of these new compounds took less than six months, according to historical satellite data. The government has also added more factories within camp and prison compounds during that time, suggesting the expansion of forced labor within the region. Construction was still ongoing as of this month.

“People are living in horror in these places,” said 49-year-old Zhenishan Berdibek, who was detained in a camp in the Tacheng region for much of 2018. “Some of the younger people were not as tolerant as us — they cried and screamed and shouted.” But Berdibek, a cancer survivor, couldn’t muster the energy. As she watched the younger women get dragged away to solitary confinement, “I lost my hope,” she said. “I wanted to die inside the camp.”

BuzzFeed News identified 268 newly built compounds by cross-referencing blanked-out areas on Baidu Maps — a Google Maps–like tool that’s widely used in China — with images from external satellite data providers. These compounds often contained multiple detention facilities.

This map shows the locations of facilities bearing the hallmarks of prisons and internment camps found in this investigation. Note: Many satellite images in this map are from before 2017, meaning that although you can zoom in, you won’t always be able to see the evidence of possible camps.

Locations identified or corroborated by other sources. Satellite images — perimeter walls and guard towers. Satellite images — walls and barbed wire but no guard towers. Detention Center built before 2017. Likely used for detention in the past but now closed or reduced security.

BuzzFeed News; Source: Analysis of satellite imagery using Google Earth, Planet Labs, and the European Space Agency's Sentinel Hub

Ninety-two of these facilities have been identified or verified as detention centers by other sources, such as government procurement documents, academic research, or, in 19 cases, visits by journalists.

Another 176 facilities have been established by satellite imagery alone. The images frequently show thick walls at the perimeter, and often, barbed wire fencing that creates pens and corridors in the courtyards. Many compounds in the region are walled, but the facilities identified by BuzzFeed News have much heavier fortifications. At 121 of these compounds, they also show guard towers, often built into the perimeter wall.

In response to a detailed list of questions about this article as well as a list of GPS coordinates of facilities identified in this article, the Chinese Consulate in New York said “the issue concerning Xinjiang is by no means about human rights, religion or ethnicity, but about combating violent terrorism and separatism,” adding that it was a “groundless lie” that a million Uighurs have been detained in the region.

“Xinjiang has set up vocational education and training centers in order to root out extreme thoughts, enhance the rule of law awareness through education, improve vocational skills and create employment opportunities for them, so that those affected by extreme and violent ideas can return to society as soon as possible,” the consulate added, saying human rights are protected in the centers and that “trainees have freedom of movement.” But it also compared its program to “compulsory programs for terrorist criminals” it said are taking place in other countries including the US and UK.

China's Foreign Ministry and Baidu did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The new facilities are scattered across every populated area of the region, and several are large enough to accommodate 10,000 prisoners at a minimum, based on their size and architectural features. (One of the reporters on this story is a licensed architect.)

Unlike early sites, the new facilities appear more permanent and prisonlike, similar in construction to high-security prisons in other parts of China. The most highly fortified compounds offer little space between buildings, tiny concrete-walled yards, heavy masonry construction, and long networks of corridors with cells down either side. Their layouts are cavernous, allowing little natural light to the interior of the buildings. BuzzFeed News could see how rooms were laid out at some high-security facilities by examining historical satellite photos taken as they were being constructed, including photos of buildings without roofs.

With at least tens of thousands of detainees crowded into government buildings repurposed as camps by the end of 2017, the government began building the largest new facilities in the spring of 2018. Several were complete by October 2018, with further facilities built through 2019 and construction of a handful more continuing even now.

The government has said its camps are schools and vocational training centers where detainees are “deradicalized.” The government’s own internal documentation about its policies in Xinjiang has used the term “concentration,” or 集中, to describe “educational schools.”

The government claims that its campaign combats extremism in the region. But most who end up in these facilities are not extremists of any sort.

Downloading WhatsApp, which is banned in China, maintaining ties with family abroad, engaging in prayer, and visiting a foreign website are all offenses for which Muslims have been sent to camps, according to previously leaked documents and interviews with former detainees. Because the government does not consider internment camps to be part of the criminal justice system and none of these behaviors are crimes under Chinese law, no detainees have been formally arrested or charged with a crime, let alone seen a day in court.

The compounds BuzzFeed News identified likely include extrajudicial internment camps — which hold people who are not suspected of any crime — as well as prisons. Both types of facilities have security features that closely resemble each other. Xinjiang’s prison population has grown massively during the government’s campaign: In 2017, the region had 21% of all arrests in China, despite making up less than 2% of the national population — an eightfold increase from the year before, according to a New York Times analysis of government data. Because China’s Communist Party–controlled courts have a more than 99% conviction rate, the overwhelming majority of those arrests likely resulted in convictions.

“One day I saw a pregnant woman in shackles. Another woman had a baby in her arms, she was breastfeeding.”

People detained in the camps told BuzzFeed News they were subjected to torture, hunger, overcrowding, solitary confinement, forced birth control, and a range of other abuses. They said they were put through brainwashing programs focusing on Communist Party propaganda and made to speak only in the Chinese language. Some former detainees said they were forced to labor without pay in factories.

The government heavily restricts the movements of independent journalists and researchers in the region, and heavily censors the internet and its own domestic media. Muslim minorities can be punished for posts on social media. But satellite images that are collected from independent providers remain outside the scope of Chinese government censorship.

Other kinds of evidence have also occasionally leaked out. In September, a drone video emerged showing hundreds of blindfolded men with their heads shaven and their arms tied behind their backs, wearing vests that say “Kashgar Detention Center.” Nathan Ruser, a researcher at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute who has done extensive satellite imagery analysis of the detention and prison systems in Xinjiang, said the video shows a prisoner transfer that took place in April 2019 — months after the government first said the system was for vocational training. Previous analyses, including by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in November 2018, identified several dozen early camps.

“The internment and assimilation program in Xinjiang has the overall logic of colonial genocides in North America, the formalized racism of apartheid, the industrial-scale internment of Germany's concentration camps, and the police-state penetration into everyday life of North Korea,” said Rian Thum, a scholar of the history of Islam in China at the University of Nottingham.

The campaign has done deep damage to many Muslim minority groups — but especially Uighurs, who are by far the most populous ethnic minority group in Xinjiang and do not have ties to any other country. The Chinese government has heavily penalized expressions of Turkic minority culture, from Kazakh- and Uighur-language education to the practice of Islam outside of state-controlled mosques. This, combined with forced sterilizations, has led some critics to say that the campaign qualifies as genocide under international law. The Trump administration is reportedly discussing whether to formally call it a genocide, and a spokesperson for Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee for president, said on Tuesday that Biden supports the label.

“These are peaceful people in concentration camps,” said Abduweli Ayup, a Uighur linguist who was jailed and later exiled from Xinjiang after opening kindergartens that taught Uighur children in their own language. “They are businessmen and scholars and engineers. They are our musicians. They are doctors. They are shopkeepers, restaurant owners, teachers who used Uighur textbooks.

“These are the pillars of our society. Without them, we cannot exist.”

The Chinese flag is seen behind razor wire at a housing compound in Yangisar, south of Kashgar, in China's western Xinjiang region, June 4, 2019.

The position of Muslim minorities, particularly Uighurs, in China has been fraught since the Communist Party came to power in 1949. But conditions deteriorated quickly starting in 2016, when the government implemented a system of heavy-handed surveillance and policing as a means to push Muslims into a growing internment camp system for “transformation through education.” Chen, the region’s party boss, called on officials to “round up everyone who should be rounded up.”

Thousands were. Tursunay Ziyawudun, who was detained in March 2018, was one of them. When she arrived at the camp’s gates, she saw hundreds of people around her removing their jewelry, shoelaces, and belts. They were being “processed,” she said, to enter the camp through a security checkpoint.

Early on, the government remade schools, retirement homes, hospitals, and other public buildings into internment camps. There were other, older detention centers available too — BuzzFeed News identified 47 built before 2017 that have been used to lock people up in the region.

Some detention facilities are geared toward releasing detainees after several months; in others, detainees may be sentenced to prison terms, said Adrian Zenz, a leading researcher on the abuses in Xinjiang. Three former detainees interviewed by BuzzFeed News said they were held for months in detention without any charges against them — far longer than is allowed by law — before they were transferred to internment camps. The detentions picked up speed in 2017, and numbers in the camps quickly swelled until the inmates were living on top of each other.

BuzzFeed News interviewed 28 former detainees from the region, many of whom described being blindfolded and handcuffed, much like the men shown in the video. Many spoke through an interpreter. They are among a tiny minority of former detainees who were released and left the country — but they described a brutal system that they saw growing and changing with their own eyes.

Most recalled being frequently moved from camp to camp — a tactic that many believed was meant to combat overcrowding in the first generation of makeshift facilities. At the beginning of the campaign, hundreds of people were arriving on a daily basis. New batches of detainees always seemed to be coming and going.

Some former detainees described sleeping two to a twin bed, or even sleeping in shifts when there was not enough room to house all the detainees. Almost all said they received meager quantities of rice, steamed buns, and porridge, and little or no meat or other protein.

Orynbek Koksebek, a 40-year-old ethnic Kazakh, was first detained relatively early in the campaign, around the end of 2017. At first, he slept in a room with seven other men, and everyone had a bed to themselves. But within a few months, he began to notice more and more people arriving. “One day I saw a pregnant woman in shackles,” he said. “Another woman had a baby in her arms, she was breastfeeding.”

By February 2018, there were 15 men in his room, he said.

“Some of us had to share blankets or sleep on the floor,” he said. “They told us later that some of us would be given prison sentences or transferred to other camps.”

Camp officials regularly forced detainees to memorize Communist Party propaganda and Chinese characters in classrooms. But some former detainees said their facilities were too crowded for even this — instead, they had to sit on plastic stools next to their beds and stare at textbooks, sitting with their backs perfectly straight while cameras monitored them. Camp guards told them there were too many people to fit in classrooms.

For Koksebek, the claustrophobia was unbearable.

“There was a window in our room, but it was so high I couldn’t see much other than a patch of sky,” he said. “I used to wish I were a bird so I could have the freedom to fly.”

The camp at Shufu, in Xinjiang, seen by satellite on April 26, 2020. BuzzFeed News; Google Maps

On a frigid, overcast morning last December, Shohrat Zakir, the region’s governor and second-most-powerful official, gave a rare press conference at China’s State Council Information Office, located in a closed compound in central Beijing. The office is one of only a handful of government bodies in China that regularly briefs both local and international journalists, and Zakir sat with four other officials at a long podium at the front of the small room. The officials took the opportunity to tout the region’s economic growth and claim China’s campaign against terrorism in Xinjiang has been a success, calling the US government hypocritical for its criticism of China’s human rights abuses. But Zakir was the one who made international headlines.

Of those held in the camps as “trainees,” Zakir painted a rosy picture. They “have all graduated, and have realized stable employment with the government’s help, improved their quality of life, and are enjoying a happy life,” he said.

Even as reporters were scribbling down his remarks, about 2,500 miles away in Xinjiang, construction was wrapping up on a massive high-security compound near the Uighur heartland county of Shufu, just south of a winding river that flows through a countryside dotted by livestock farms. Shufu is small by Chinese standards, with a population of about 300,000 people. It has a main drag with a post office, a lottery ticket vendor, and eateries selling steamed buns and beef noodle soup. The camp was built on farmland less than a 20-minute drive away.

Before workers started construction last March, the land beneath the Shufu site was farmland too, blanketed with green vegetation. By August, workers had built a thick perimeter enclosure, with guard towers looming in the corners and in the center of walls that rise nearly 6 meters, or more than 19 feet, satellite images show. Next came the buildings inside, organized in U-shaped groups, with two five-story structures alongside a two-story one forming the base of the U. By October, two rows of barbed wire fencing appeared on either side of the main concrete-walled compound, its shadow visible in satellite images.

Just outside the walls, on the western side of the compound, two guard buildings were built — distinguished by the narrow walled pathways leading from them up to the wall that would allow guards to access the guard towers and the tops of the walls for patrols. In front of the entrance, a series of buildings provided space for prison offices and police buildings. In total BuzzFeed News estimates that there is room for approximately 10,500 prisoners at this compound — which would help provide a long-term solution to overcrowding.

“I wasn’t happy or sad. I couldn’t feel anything. Even when I was reunited with my relatives in Kazakhstan, they asked me why I didn’t seem happy to see them after so long.”

Ruser reviewed satellite images of the compound and said it was a newly built detention camp. “The vast majority of camps have watchtowers, internal fencing, and a strong external wall entranceway or exit,” he said.

Unlike the old, repurposed camps, new prisons and camps such as this one have higher security, with gates up to four stories tall and thicker walls along their borders, often with further layers of barbed wire on either side of the main walls. These features suggest they are capable of holding much larger groups of people in long-term detention.

The camps can contain not only cells where detainees sleep, but also classrooms, clinics, canteens, stand-alone shower facilities, solitary confinement rooms, police buildings, administrative offices, and small visitor centers, former detainees told BuzzFeed News. Many of the compounds also contain factories, distinguished by their blue, powder-coated metal roofs and steel frames, which are visible in satellite photos taken while they were being constructed. The police buildings, including for guards and administrative personnel, are usually located by the entrances of the compounds.

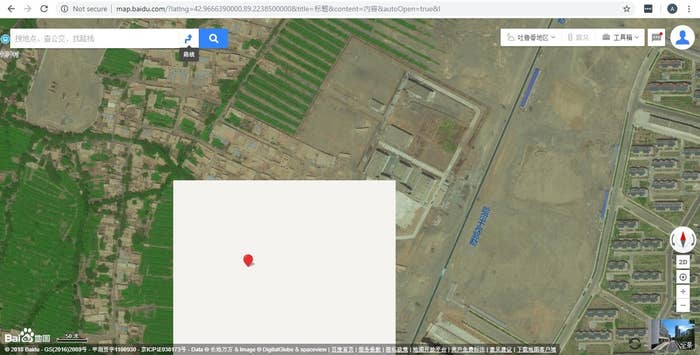

The locations of these camps and prisons in Xinjiang are not readily available. However, blanked-out portions of maps on China's Baidu make it possible to use satellite imagery to find and analyze them.

Satellite maps, like Google Earth, are made up of a grid of rectangular tiles. On Baidu, the Chinese search giant that has a map service much like Google’s, BuzzFeed News discovered that spaces containing camps, military bases, or other politically sensitive facilities were overlaid with plain light gray tiles. These “mask” tiles appeared upon zooming in on the location. These look different from the darker gray, watermarked tiles that appear when Baidu cannot load something. The “mask” tiles were also present at other locations where camps had been visited and verified by journalists, though they have since been removed.

Dabancheng District, Ürümqi Prefecture

Baidu; Planet Labs

Shule County, Kashgar Prefecture

Baidu; Planet Labs

Gaochang District, Turpan Prefecture

Baidu; Planet Labs

BuzzFeed News identified the compounds using other satellite maps — provided by Google Earth, Planet Labs, and the European Space Agency’s Sentinel Hub — which do not mask those images. For some locations where high-resolution images were not publicly available, Planet Labs used its own satellite to take new pictures, then provided them to BuzzFeed News. Read more here about how this investigation was conducted.

The images showed the facilities being built over a period of months. Details from the images offer a sense of size and scale: Counting the number of windows in building facades, for example, shows how many stories they contain.

Often, these compounds were built next door to an older prison, sharing parking lots, administrative facilities, and police barracks with the older facility, satellite images show.

BuzzFeed News found an additional 50 more compounds that were likely used for internment in the past but have lost some security features, including barbed wire fencing within compounds used to create rectangular pens, closed passages between buildings, and guard towers, with a small number having been demolished.

Ruser and other experts said this does not suggest the Chinese government is pulling back from its campaign. Many of those facilities likely still operate as low-security camps, he said. The far more important trend in Xinjiang, he said, is the government’s increased use of higher-security prisons and detention facilities.

In response to questions, the Chinese Consulate in New York echoed Zakir's December statement.

"All trainees who received courses in standard spoken and written Chinese, understanding of the law, vocational skills, and deradicalization have completed their training, secured stable employment in the society, and are living a normal life," it said.

All of the detainees interviewed by BuzzFeed News were released too long ago to have spent any time in one of the brand-new facilities — many said that before they escaped China for good, they were kept under de facto house or town arrest, unable to venture past the borders of their villages without obtaining permission from a police officer. Many — especially those with less formal education — had no idea what type of facility they were held in or even why they had been detained in the first place. They said they often drew conclusions based on weekly interrogation sessions, where police asked about actions that made them “untrustworthy.”

An older ethnic Kazakh man named Nurlan Kokteubai recognized the camp he was taken to as soon as he arrived in September 2017. Not long before, it had been a middle school.

“My daughter went to that school,” he said. “I had picked her up there before.”

Smile lines appear on Kokteubai’s deeply wrinkled face when he talks about his daughter, who was born in 1992. She later moved to Kazakhstan, where many ethnic Kazakhs from China emigrate because of the Kazakh government’s resettlement policy for people of Kazakh descent. There, she and her husband campaigned relentlessly for Kokteubai’s release in YouTube videos and long letters to human rights groups. He believes his eventual release in March 2018 was due to her campaign. Inside the camp, instead of classrooms where students like his daughter might have studied math or history, Kokteubai saw dorm rooms overcrowded with as many as 40 or 50 men each sleeping on too few bunk beds.

Though the compound itself wasn’t new, it had many updated features, such as high walls and barbed wire around the compound. And the camp was now dotted with CCTV cameras, which a guard told him could film objects as far as 200 meters away.

Another thing that was new: When you entered the gate, a huge red plaque greeted you. “Let’s learn the spirit of the 19th Communist Party Congress,” it said.

Like Kokteubai, several former detainees interviewed by BuzzFeed News said after arriving, they recognized the facilities in which they were held because they had walked or driven past them, or even visited them in their previous incarnations. But these repurposed facilities were never meant to house prisoners and were not big enough to hold all the Muslim minorities the Chinese government intended to detain.

In early 2019, workers started clearing land to expand a camp south of Ürümqi, in a town called Dabancheng, that had become infamous after reporters from BBC and Reuters visited the year before. The camp at Dabancheng was already one of the largest internment facilities in the region, capable in October 2018 of housing up to 32,500 people, according to an architectural analysis by BuzzFeed News. Since the expansion, it is now capable of housing some 10,000 more people. By November of last year another, separate compound had been completed, this one capable of holding a further 10,000 people — for a total capacity of more than 40,000, comparable to the size of the town of Niagara Falls.

"These facilities display characteristics consistent with extrajudicial detention facilities in the Xinjiang region that CSIS has previously analyzed," said Amy Lehr, director of the human rights program at Washington DC-based think tank CSIS after examining the three camps referenced in this article.

Dabancheng

District,

Ürümqi, Xinjiang

Planet Labs; Google Maps

The camp at Dabancheng, Ruser said, “is the main catchment camp for Ürümqi. It’s 2 km (1.2 miles) long and was expanded late last year an extra kilometer with a new facility across the road to the west.” By comparison, the camp is about half the length of Central Park.

Kokteubai never found out precisely why he was detained. Because he’s ethnic Kazakh, he was eventually able to settle in Kazakhstan.

On the day he was released, he expected to feel joy, relief, something. Instead he felt nothing at all.

“I wasn’t happy or sad. I couldn’t feel anything,” he said. “Even when I was reunited with my relatives in Kazakhstan, they asked me why I didn’t seem happy to see them after so long.”

“It’s something I can’t explain,” he said. “It’s like my feelings died while I was in there.” ●

What They Saw: Dozens Of Ex-Prisoners Detail The Horrors Of China’s Detention Camps

Hundreds of thousands of Muslims have been held inside Xinjiang’s camps, but very little is known about life inside. BuzzFeed News spoke to dozens of ex-detainees.

Ex-Prisoners Detail The Horrors Of China’s Detention Camps

This project was supported by the Open Technology Fund, the Pulitzer Center, and the Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism.This is Part 2 of a BuzzFeed News investigation. For Part 1, click here.

ALMATY — Maybe the police officers call you first. Or maybe they show up at your workplace and ask your boss if they can talk to you. In all likelihood they will come for you at night, after you’ve gone to bed.

In Nursaule’s case, they turned up at her home just as she was fixing her husband a lunch of fresh noodles and lamb.

For the Uighurs and Kazakhs in China’s far west who have found themselves detained in a sprawling system of internment camps, what happens next is more or less the same. Handcuffed, often with a hood over their heads, they are brought by the hundreds to the tall iron gates.

Thrown into the camps for offenses that range from wearing a beard to having downloaded a banned app, upward of a million people have disappeared into the secretive facilities, according to independent estimates. The government has previously said the camps are meant to provide educational or vocational training to Muslim minorities. Satellite images, such as those revealed in a BuzzFeed News investigation on Thursday, offer bird’s eye hints: guard towers, thick walls, and barbed wire. Yet little is still known about day-to-day life inside.

BuzzFeed News interviewed 28 former detainees from the camps in Xinjiang about their experiences. Most spoke through an interpreter. They are, in many ways, the lucky ones — they escaped the country to tell their tale. All of them said that when they were released, they were made to sign a written agreement not to disclose what happens inside. (None kept copies — most said they were afraid they would be searched at the border when they tried to leave China.) Many declined to use their names because, despite living abroad, they feared reprisals on their families. But they said they wanted to make the world aware of how they were treated.

The stories about what detention is like in Xinjiang are remarkably consistent — from the point of arrest, where people are swept away in police cars, to the days, weeks, and months of abuse, deprivation, and routine humiliation inside the camps, to the moment of release for the very few who get out. They also offer insight into the structure of life inside, from the surveillance tools installed — even in restrooms — to the hierarchy of prisoners, who said they were divided into color-coded uniforms based on their assumed threat to the state. BuzzFeed News could not corroborate all details of their accounts because it is not possible to independently visit camps and prisons in Xinjiang.

“They treated us like livestock. I wanted to cry. I was ashamed, you know, to take off my clothes in front of others.”

Their accounts also give clues into how China’s mass internment policy targeting its Muslim minorities in Xinjiang has evolved, partly in response to international pressure. Those who were detained earlier, particularly in 2017 and early 2018, were more likely to find themselves forced into repurposed government buildings like schoolhouses and retirement homes. Those who were detained later, from late 2018, were more likely to have seen factories being built, or even been forced to labor in them, for no pay but less oppressive detention.

In response to a list of questions for this article, the Chinese Consulate in New York said that "the basic principle of respecting and protecting human rights in accordance with China's Constitution and law is strictly observed in these centers to guarantee that the personal dignity of trainees is inviolable."

"The centers are run as boarding facilities and trainees can go home and ask for leave to tend to personal business. Trainees' right to use their own spoken and written languages is fully protected ... the customs and habits of different ethnic groups are fully respected and protected," the consulate added, saying that "trainees" are given halal food for free and that they can decide whether to "attend legitimate religious activities" when they go home.

China's Foreign Ministry did not respond to several requests for comment.

Nursaule’s husband was watching TV the day she was detained in late 2017 near Tacheng city, she said. She was in the kitchen when there was a sharp knock at the front door. She opened it to find a woman wearing ordinary clothing flanked by two uniformed male police officers, she said. The woman told her she was to be taken for a medical checkup.

At first, Nursaule, a sixtysomething Kazakh woman whose presence is both no-nonsense and grandmotherly, was glad. Her legs had been swollen for a few days, and she had been meaning to go to the doctor to have them looked at.

Nursaule’s stomach began to rumble. The woman seemed kind, so Nursaule asked if she could return to pick her up after she’d eaten lunch. The woman agreed. But then she said something strange.

“She told me to take off my earrings and necklace before going with them, that I shouldn’t take my jewelry where I was going,” Nursaule said. “It was only then that I started to feel afraid.”

After the police left, Nursaule called her grown-up daughter to tell her what happened, hoping she’d have some insight. Her daughter told her not to worry — but something in her tone told Nursaule there was something wrong. She began to cry. She couldn’t eat a bite of her noodles. Many hours later, after the police had interrogated her for hours, she realized that she was starving. But the next meal she would eat would be within the walls of an internment camp.

Like Nursaule, those detained all reported being given a full medical checkup before being taken to the camps. At the clinic, samples of their blood and urine were collected, they said. They also said they sat for interviews with police officers, answering questions on their foreign travel, personal beliefs, and religious practices.

“They asked me, ‘Are you a practicing Muslim?’ ‘Do you pray?’” said Kadyrbek Tampek, a livestock farmer from the Tacheng region, which lies in the north of Xinjiang. “I told them that I have faith, but I don’t pray.” Afterward, the police officers took his phone. Tampek, a soft-spoken 51-year-old man who belongs to Xinjiang’s ethnic Kazakh minority, was first sent to a camp in December 2017 and said he was later forced to work as a security guard.

After a series of blood tests, Nursaule was taken to a separate room at the clinic, where she was asked to sign some documents she couldn’t understand and press all 10 of her fingers on a pad of ink to make fingerprints. Police interrogated her about her past, and afterward, she waited for hours. Finally, past midnight, a Chinese police officer told her she would be taken to “get some education.” Nursaule tried to appeal to the Kazakh officer translating for him — she does not speak Chinese — but he assured her she would only be gone 10 days.

After the medical exam and interview, detainees were taken to camps. Those who had been detained in 2017 and early in 2018 described a chaotic atmosphere when they arrived — often in tandem with dozens or even hundreds of other people, who were lined up for security screenings inside camps protected by huge iron gates. Many said they could not recognize where they were because they had arrived in darkness, or because police placed hoods over their heads. But others said they recognized the buildings, often former schools or retirement homes repurposed into detention centers. When Nursaule arrived, the first thing she saw were the heavy iron doors of the compound, flanked by armed police.

“I recognized those dogs. They looked like the ones the Germans had.”

Once inside, they were told to discard their belongings as well as shoelaces and belts — as is done in prisons to prevent suicide. After a security screening, detainees said they were brought to a separate room to put on camp uniforms, often walking through a passageway covered with netting and flanked by armed guards and their dogs. “I recognized those dogs,” said one former detainee who declined to share his name. He used to watch TV documentaries about World War II, he said. “They looked like the ones the Germans had.”

“We lined up and took off our clothes to put on blue uniforms. There were men and women together in the same room,” said 48-year-old Parida, a Kazakh pharmacist who was detained in February 2018. “They treated us like livestock. I wanted to cry. I was ashamed, you know, to take off my clothes in front of others.”

More than a dozen former detainees confirmed to BuzzFeed News that prisoners were divided into three categories, differentiated by uniform colors. Those in blue, like Parida and the majority of the people interviewed for this article, were considered the least threatening. Often, they were accused of minor transgressions, like downloading banned apps to their phones or having traveled abroad. Imams, religious people, and others considered subversive to the state were placed in the strictest group — and were usually shackled even inside the camp. There was also a mid-level group.

The blue-clad detainees had no interaction with people in the more “dangerous” groups, who were often housed in different sections or floors of buildings, or stayed in separate buildings altogether. But they could sometimes see them through the window, being marched outside the building, often with their hands cuffed. In Chinese, the groups were referred to as “ordinary regulation,” “strong regulation,” and “strict regulation” detainees.

For several women detainees, a deeply traumatic humiliation was having their long hair cut to chin length. Women were also barred from wearing traditional head coverings, as they are in all of Xinjiang.

“I wanted to keep my hair,” said Nursaule. “Keeping long hair, for a Kazakh woman, is very important. I had grown it since I was a little girl, I had never cut it in my life. Hair is the beauty of a woman.”

“I couldn’t believe it,” she said. “They wanted to hack it off.”

After the haircut, putting her hand to the ends of her hair, she cried.

From the moment they stepped inside the compounds, privacy was gone. Aside from the overwhelming presence of guards, each room was fitted with two video cameras, all the former detainees interviewed by BuzzFeed News confirmed. Cameras could also be seen in bathrooms, and throughout the building. In some camps, according to more than a dozen former detainees, dorms were outfitted with internal and external doors, one of which required an iris or thumbprint scan for guards to enter. The internal doors sometimes had small windows through which bowls of food could be passed.

Periodically, the detainees were subject to interrogations, where they’d have to repeat again and again the stories of their supposed transgressions — religious practices, foreign travel, and online activities. These sessions were carefully documented by interrogators, they said. And they often resulted in detainees writing “self-criticism.” Those who could not read and write were given a document to sign.

None of the former detainees interviewed by BuzzFeed News said they contemplated escaping — this was not a possibility.

Camp officials would observe the detainees’ behavior during the day using cameras, and communicate with detainees over intercom.

Camps were made up of multiple buildings, including dorms, canteens, shower facilities, administrative buildings, and, in some cases, a building where visitors were hosted. But most detainees said they saw little outside their own dorm room buildings. Detainees who arrived early in the government’s campaign — particularly in 2017 — reported desperately crowded facilities, where people sometimes slept two to a twin bed, and said new arrivals would come all the time.

Dorm rooms were stacked with bunk beds, and each detainee was given a small plastic stool. Several former detainees said that they were forced to study Chinese textbooks while sitting rigidly on the stools. If they moved their hands from their knees or slouched, they’d be yelled at through the intercom.

Detainees said there was a shared bathroom. Showers were infrequent, and always cold.

Some former detainees said there were small clinics within the camps. Nursaule remembered being taken by bus to two local hospitals in 2018. The detainees were chained together, she said.

People were coming and going all the time from the camp where she stayed, she said.

“She told me to take off my earrings and necklace before going with them, that I shouldn’t take my jewelry where I was going. It was only then that I started to feel afraid.”

Surveillance was not limited to cameras and guards. At night, the detainees themselves were forced to stand watch in shifts over other inmates in their own rooms. If anyone in the room acted up — getting into arguments with each other, for example, or speaking Uighur or Kazakh instead of Chinese — those on watch could be punished as well. Usually they were beaten, or, as happened more often to women, put into solitary confinement. Several former detainees said that older men and women could not handle standing for many hours and struggled to keep watch. The atmosphere was so crowded and tense that arguments sometimes broke out among detainees — but these were punished severely.

“They took me down there and beat me,” said one former detainee. “I couldn’t tell you where the room was because they put a hood over my head.”

Nursaule was never beaten, but one day, she got into a squabble with a Uighur woman who was living in the same dorm room. Guards put a sack over her head and took her to the solitary room.

There, it was dark, with only a metal chair and a bucket. Her ankles were shackled together. The room was small, about 10 feet by 10 feet, she said, with a cement floor. There was no window. The lights were kept off, so guards used a flashlight to find her, she said.

After three days had passed by, she was taken back up to the cell.

Residents at the Kashgar city vocational educational training center attend a Chinese lesson during a government-organized visit in Kashgar, Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, China, Jan. 4, 2019.

The government has said that “students” in the camps receive vocational training, learn the Chinese language, and become “deradicalized.” Former detainees say this means they were brainwashed with Communist Party propaganda and forced to labor for free in factories.

State media reports have emphasized the classroom education that takes place in the camps, claiming that detainees are actually benefiting from their time there. But several former detainees told BuzzFeed News that there were too many people to fit inside the classroom, so instead they were forced to study textbooks while sitting on their plastic stools in their dorm rooms.

Those who did sit through lessons in classrooms described them all similarly. The teacher, at the front of the room, was separated from the detainees by a transparent wall or a set of bars, and he or she taught them Mandarin or about Communist Party dogma. Guards flanked the classroom, and some former detainees said they carried batons and even hit “pupils” when they made mistakes about Chinese characters.

Nearly every former detainee who spoke to BuzzFeed News described being moved from camp to camp, and noted that people always seemed to be coming and going from the buildings where they were being held. Officials did not appear to give reasons for these moves, but several former detainees chalked it up to overcrowding.

Among them was Dina Nurdybai, a 27-year-old Kazakh woman who ran a successful clothing manufacturing business. After being first detained on October 14, 2017, Nurdybai was moved between five different camps — ranging from a compound in a village where horses were raised to a high-security prison.

In the first camp, “it seemed like 50 new people were coming in every night. You could hear the shackles on their legs,” she said.

Nursaule never expected to be released.

“It was dinner time and we were lining up at the door,” she said. “They called my name and another Kazakh woman’s name.” It was December 23, 2018.

She was terrified — she had heard that some detainees were being given prison sentences, and she wondered if she might be among them. China does not consider internment camps like the ones she was sent to be part of the criminal justice system — no one who is sent to a camp is formally arrested or charged with a crime.

Nursaule had heard that prisons — which disproportionately house Uighurs and Kazakhs — could be even worse than internment camps. She whispered to the other woman, “Are we getting prison terms?” The two were taken in handcuffs to a larger room and told to sit on plastic stools. Then an officer undid the handcuffs.

He asked if Nursaule wanted to go to Kazakhstan. She said yes. He then gave her a set of papers to sign, promising never to tell anyone what she had experienced. She signed it, and they allowed her to leave — to live under house arrest until she left for Kazakhstan for good. The day after, her daughter arrived with her clothes.

Nearly all of the former detainees interviewed by BuzzFeed News told a similar story about being asked to sign documents that said they’d never discuss what happened to them. Those who didn’t speak Chinese said they couldn’t even read what they were asked to sign.

Some of them were told the reasons they had been detained, and others said they never got an answer.

“In the end they told me I was detained because I had used ‘illegal software,’” Nurdybai said — WhatsApp.

A giant national flag is displayed on the hillside of the peony valley scenic area in the Tacheng region, in northwest China, May 13, 2019.

Nursaule’s daughter, who is in her late twenties, is a nurse who usually works the night shift at a local hospital in Xinjiang, starting at 6 p.m. Nursaule worries all the time about her — about how hard she works, and whether she might be detained someday too. After Nursaule was eventually released from detention, it was her daughter who cared for her, because her husband had been detained too.

Like for other Muslim minorities, government authorities have taken her daughter’s passport, Nursaule said, so she cannot come to Kazakhstan.

Snow fell softly outside the window as Nursaule spoke about what had happened to her from an acquaintance’s apartment in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, where a cheery plastic tablecloth printed with cartoon plates of pasta covered the coffee table. Nursaule spoke slowly and carefully in her native Kazakh, with the occasional bitter note creeping into her voice, long after the milky tea on the table had grown cold.

But when she asked that her full name not be used in this article, she began to weep — big, heaving sobs pent up from the pain she carried with her, from talking about things she could hardly bear to remember or relate, even to her husband.

She was thinking about her daughter, she said, and about what could happen if Chinese officials discovered she spoke about her time in the camps. It is the reason that she, like so many former detainees and prisoners, has never spoken publicly about what was done to her.

“I am still afraid of talking about this,” she said. “I can’t stand it anymore. I can’t bear it.”

“It makes me suffer to tell you this,” she said.

“But I feel that I have to tell it.” ●

Blanked-Out Spots On China's Maps Helped Us Uncover Xinjiang's Camps

China's Baidu blanked out parts of its mapping platform. We used those locations to find a network of buildings bearing the hallmarks of prisons and internment camps in Xinjiang. Here's how we did it.

China's Baidu blanked out parts of its mapping platform. We used those locations to find a network of buildings bearing the hallmarks of prisons and internment camps in Xinjiang. Here's how we did it.

Baidu / Via map.baidu.com

A masked tile on Baidu Maps.

This project was supported by the Open Technology Fund, the Pulitzer Center, and the Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism.

In the summer of 2018, as it became even harder for journalists to work effectively in Xinjiang, a far-western region of China, we started to look at how we could use satellite imagery to investigate the camps where Uighurs and other Muslim minorities were being detained. At the time we began, it was believed that there were around 1,200 camps in existence, while only several dozen had been found. We wanted to try to find the rest.

Our breakthrough came when we noticed that there was some sort of issue with satellite imagery tiles loading in the vicinity of one of the known camps while using the Chinese mapping platform Baidu Maps. The satellite imagery was old, but otherwise fine when zoomed out — but at a certain point, plain light gray tiles would appear over the camp location. They disappeared as you zoomed in further, while the satellite imagery was replaced by the standard gray reference tiles, which showed features such as building outlines and roads.

At that time, Baidu only had satellite imagery at medium resolution in most parts of Xinjiang, which would be replaced by their general reference map tiles when you zoomed in closer. That wasn’t what was happening here — these light gray tiles at the camp location were a different color than the reference map tiles and lacked any drawn information, such as roads. We also knew that this wasn’t a failure to load tiles, or information that was missing from the map. Usually when a map platform can’t display a tile, it serves a standard blank tile, which is watermarked. These blank tiles are also a darker color than the tiles we had noticed over the camps.

Once we found that we could replicate the blank tile phenomenon reliably, we started to look at other camps whose locations were already known to the public to see if we could observe the same thing happening there. Spoiler: We could. Of the six camps that we used in our feasibility study, five had blank tiles at their location at zoom level 18 in Baidu, appearing only at this zoom level and disappearing as you zoomed in further. One of the six camps didn’t have the blank tiles — a person who had visited the site in 2019 said it had closed, which could well have explained it. However, we later found that the blank tiles weren’t used in city centers, only toward the edge of cities and in more rural areas. (Baidu did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Having established that we could probably find internment camps in this way, we examined Baidu's satellite tiles for the whole of Xinjiang, including the blank masking tiles, which formed a separate layer on the map. We analyzed the masked locations by comparing them to up-to-date imagery from Google Earth, the European Space Agency’s Sentinel Hub, and Planet Labs.

In total there were 5 million masked tiles across Xinjiang. They seemed to cover any area of even the slightest strategic importance — military bases and training grounds, prisons, power plants, but also mines and some commercial and industrial facilities. There were far too many locations for us to sort through, so we narrowed it down by focusing on the areas around cities and towns and major roads.

Prisons and internment camps need to be near infrastructure — you need to get large amounts of building materials and heavy machinery there to build them, for starters. Chinese authorities would have also needed good roads and railways to bring newly detained people there by the thousand, as they did in the early months of the mass internment campaign. Analyzing locations near major infrastructure was therefore a good way to focus our initial search. This left us with around 50,000 locations to look at.

We began to sort through the mask tile locations systematically using a custom web tool that we built to support our investigation and help manage the data. We analyzed the whole of Kashgar prefecture, the Uighur heartland, which is in the south of Xinjiang, as well as parts of the neighboring prefecture, Kizilsu, in this way. After looking at 10,000 mask tile locations and identifying a number of facilities bearing the hallmarks of detention centers, prisons, and camps, we had a good idea of the range of designs of these facilities and also the sorts of locations in which they were likely to be found.

We quickly began to notice how large many of these places are — and how heavily securitized they appear to be, compared to the earlier known camps. In site layout, architecture, and security features, they bear greater resemblance to other prisons across China than to the converted schools and hospitals that formed the earlier camps in Xinjiang. The newer compounds are also built to last, in a way that the earlier conversions weren’t. The perimeter walls are made of thick concrete, for example, which takes much longer to build and perhaps later demolish, than the barbed wire fencing that characterizes the early camps.

In almost every county, we found buildings bearing the hallmarks of detention centers, plus new facilities with the characteristics of large, high-security camps and/or prisons. Typically, there would be an older detention center in the middle of the town, while on the outskirts there would be a new camp and prison, often in recently developed industrial areas. Where we hadn’t yet found these facilities in a given county, this pattern pushed us to keep on looking, especially in areas where there was no recent satellite imagery. Where there was no public high-resolution imagery, we used medium-resolution imagery from Planet Labs and Sentinel to locate likely sites. Planet was then kind enough to give us access to high-resolution imagery for these locations and to task a satellite to capture new imagery of some areas that hadn’t been photographed in high resolution since 2006. In one county, this allowed us to see that the detention center that had previously been identified by other researchers had been demolished and to find the new prison just out of town.

This is Yiwu, Hami prefecture in Google Earth, in the most recent publicly available high-resolution imagery. The photo was taken in 2006. The white marker shows the old, now-demolished prison and the red marker shows the new one on the outskirts.

Google Earth

Here is a close-up of the location where the new prison would eventually be built.

Google Earth

Planet Labs took a new satellite image in 2020, showing the fully built facility.

Planet Labs

Prison requirements — why prisons are built where they are

There’s good reason why these places are developed close to towns. There’s the occasional camp in a more remote location, such as the sprawling internment camp in Dabancheng, but even there it’s next to a major road, with a small town nearby. Having the prison or camp close to an existing town minimizes, in principle, the distance that detainees must be transported (although there are also examples of prisoners and detainees being taken right across Xinjiang, from Kashgar to Korla, as in the drone video that reemerged recently, according to analysts). It is easier for families to visit loved ones who are in custody. Being near a town means that a prison or camp can be staffed more easily. Guards have families, their children need to go to school, their partners have jobs, they need access to healthcare, etc. Construction workers are needed to build the prison in the first place. It is also useful for amenities. Prisons and camps need electricity, water, telephone lines. It is way cheaper and easier to connect to an existing nearby network than to run new pipes and cables tens of kilometers to a more remote location.

Finally, you need a large plot of land for a prison, preferably with space to expand in the future, and this is what the recently developed industrial estates offer: large, serviced plots, close to existing towns and cities. Building in industrial estates also places the camps close to factories for forced labor. While many camps have factories within their compounds, in several cases that we know of detainees are bused to other factory sites to work.

Our list of sites

In total we identified 428 locations in Xinjiang bearing the hallmarks of prisons and detention centers. Many of these locations contain two to three detention facilities — a camp, pretrial administrative detention center, or prison. We intend to analyze these locations further and make our database more granular over the next few months.

Of these locations, we believe 315 are in use as part of the current internment program — 268 new camp or prison complexes, plus 47 pretrial administrative detention centers that have not been expanded over the past four years. We have witness testimony showing that these detention centers have frequently been used to detain people, who are often then moved on to other camps, and so we feel it is important to include them. Excluded from this 315 are 39 camps that we believe are probably closed and 11 that have closed — either they’ve been demolished or we have witness testimony that they are no longer in use. There are a further 14 locations identified by other researchers, but where our team has only been able to check the satellite evidence, which in these cases is weak. These 14 are not included in our list.

We have also located 63 prisons that we believe belong to earlier, pre-2016 programs. These facilities were typically built several years — in some cases, several decades — before the current internment program and have not been significantly extended since 2016. They are also different in style from the detention centers, known in Chinese as “kanshousuo,” and also from the newer camps. These facilities are not part of the 315 we believe to be in use as part of the current internment program and are included separately in our database.

Many of the earlier camps, which were converted from other uses, had their courtyard fencing, watchtowers, and other security features removed, often in late 2018 or early 2019. In some cases, the removal of most barricading, plus the fact that there are often cars parked in several places across the compounds, suggests that they’re no longer camps and are classified as probably closed in our database. The removal of the security features, in several cases, coincided with the opening of a larger, higher-security facility being completed nearby, suggesting that detainees may have been moved to the newer location.

Where facilities were purpose-built as camps and have had courtyard fencing removed but otherwise don’t show any change of use (like cars in the compound), we think they’re likely to still be camps — albeit with lower levels of security.

The only way to stop China from enslaving and torturing these people in concentration camps and making them do forced labor in Chinese factories is to move all manufacturing out of China. Just banning products made in Xinjiang is not enough. The Chinese will simply move the Uyghurs and other minorities to factories in other regions to continue forcing them to work as slaves.

Until international corporations move all manufacturing out of China, the atrocities in such concentration camps will continue. International corporations are complicit in all of this because they look the other way for cheap labor even as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities are forced to work as slaves.

Last edited:

Beijing has rejected US accusations that the Chinese government has detained large numbers of Muslims in the Xinjiang region in what former detainees describe as re-education centers with prison-like conditions. CNN's Matt Rivers investigates. #China #CNN #News

The only way to stop China from enslaving and torturing these people in concentration camps and making them do forced labor in Chinese factories is to move all manufacturing out of China. Just banning products made in Xinjiang is not enough. The Chinese will simply move the Uyghurs and other minorities to factories in other regions to continue forcing them to work as slaves.

Until international corporations move all manufacturing out of China, the atrocities in such concentration camps will continue. International corporations are complicit in all of this because they look the other way for cheap labor even as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities are forced to work as slaves.

The only way to stop China from enslaving and torturing these people in concentration camps and making them do forced labor in Chinese factories is to move all manufacturing out of China. Just banning products made in Xinjiang is not enough. The Chinese will simply move the Uyghurs and other minorities to factories in other regions to continue forcing them to work as slaves.

Until international corporations move all manufacturing out of China, the atrocities in such concentration camps will continue. International corporations are complicit in all of this because they look the other way for cheap labor even as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities are forced to work as slaves.

Last edited:

China’s Vanishing Muslims: Undercover In The Most Dystopian Place In The World

China’s Uighur minority live a dystopian nightmare of constant surveillance and brutal policing. At least one million of them are believed to be living in what the U.N. described as a “massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy,” while many Uighur children are taken to state-run orphanages where they're indoctrinated into Chinese customs. The Uighurs' plight has largely been kept hidden from the world, thanks to China’s aggressive attempts to suppress the story at all costs. VICE News’ Isobel Yeung posed as a tourist to gain unprecedented access to China’s western Xinjiang region, which has been nearly unreachable by journalists. She and our crew experienced China’s Orwellian surveillance and harassment first-hand during their time in Xinjiang, and captured chilling hidden-camera footage of eight Uighur men detained by police in the middle of the night. We spoke with members of the Uighur community about their experience in these camps, and about China’s attempts to silence their history and lifestyle under the cover of darkness.

The only way to stop China from enslaving and torturing these people in concentration camps and making them do forced labor in Chinese factories is to move all manufacturing out of China. Just banning products made in Xinjiang is not enough. The Chinese will simply move the Uyghurs and other minorities to factories in other regions to continue forcing them to work as slaves.

Until international corporations move all manufacturing out of China, the atrocities in such concentration camps will continue. International corporations are complicit in all of this because they look the other way for cheap labor even as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities are forced to work as slaves.

China’s Uighur minority live a dystopian nightmare of constant surveillance and brutal policing. At least one million of them are believed to be living in what the U.N. described as a “massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy,” while many Uighur children are taken to state-run orphanages where they're indoctrinated into Chinese customs. The Uighurs' plight has largely been kept hidden from the world, thanks to China’s aggressive attempts to suppress the story at all costs. VICE News’ Isobel Yeung posed as a tourist to gain unprecedented access to China’s western Xinjiang region, which has been nearly unreachable by journalists. She and our crew experienced China’s Orwellian surveillance and harassment first-hand during their time in Xinjiang, and captured chilling hidden-camera footage of eight Uighur men detained by police in the middle of the night. We spoke with members of the Uighur community about their experience in these camps, and about China’s attempts to silence their history and lifestyle under the cover of darkness.

The only way to stop China from enslaving and torturing these people in concentration camps and making them do forced labor in Chinese factories is to move all manufacturing out of China. Just banning products made in Xinjiang is not enough. The Chinese will simply move the Uyghurs and other minorities to factories in other regions to continue forcing them to work as slaves.

Until international corporations move all manufacturing out of China, the atrocities in such concentration camps will continue. International corporations are complicit in all of this because they look the other way for cheap labor even as the Uyghurs, Tibetans and other minorities are forced to work as slaves.

Last edited:

hina transferred detained Uighurs to factories used by global brands – report

At least 80,000 Uighurs working under ‘conditions that strongly suggest forced labour’

At least 80,000 Uighurs have been transferred from Xinjiang province, some of them directly from detention centres, to factories across China that make goods for dozens of global brands, according to a report from the Canberra-based Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

Using open-source public documents, satellite imagery, and media reports, the institute identified 27 factories in nine Chinese provinces that have used labourers transferred from re-education centres in Xinjiang since 2017 as part of a programme known as “Xinjiang aid”.

In conditions that “strongly suggest forced labour”, the report says, workers live in segregated dormitories, are required to study Mandarin and undergo ideological training. They are frequently subjected to surveillance and barred from observing religious practices. According to government documents analysed by the ASPI, workers are often assigned minders and have limited freedom of movement.

The factories were part of supply chains providing goods for 83 global brands, the report found, including Apple, Nike and Volkswagen among others.

China has come under mounting international scrutiny for its policies toward Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, where as many as 1.5 million people have been sent to re-education and internment camps. Beijing, which says these facilities are voluntary vocational training centres, has said in recent months that most “students” of such centres have “graduated” and returned to society.

The report from the ASPI adds to growing evidence that even after being released from the camps, former detainees are still subject to severe controls and in some cases forced labour. The report’s authors said the actual number of those sent to other parts of China as part of the work programme was “likely to be far higher” than 80,000.

“This report exposes a new phase in China’s social re-engineering campaign targeting minority citizens, revealing new evidence that some factories across China are using forced Uighur labour under a state-sponsored labour transfer scheme that is tainting the global supply chain,” the researchers concluded.

Case studies highlighted in the report, titled Uyghurs for Sale, include Qingdao Taekwang Shoes, a factory in eastern China that produces shoes for Nike. The workers were mostly Uighur women from the prefectures of Hotan and Kashgar in southern Xinjiang, and attended night classes whose curriculum was similar to that of the re-education camps.

According to government notices, workers were required to attend the “Pomegranate Seed” night school, named after a policy that aims to make ethnic minorities and the majority Han Chinese ethnic group as close as the seeds of a pomegranate. At the school, workers study Mandarin, sing the Chinese national anthem and receive “patriotic education”. Public security and other government workers were to give daily reports on the “thoughts” of the Uighur workers.

Advertisements for “government-sponsored Uighur labour” have begun to appear more frequently online, according to the researchers. One ad read: “The advantages of Xinjiang workers are: semi-military style management, can withstand hardship, no loss of personnel … minimum order 100 workers!”

The report called on China to allow multinational companies unfettered access to investigate any potential instances of abusive or forced labour in factories in China, and for companies to conduct audits and human rights due-diligence inspections.

“It is vital that, as these problems are addressed, Uighur labourers are not placed in positions of greater harm or, for example, involuntarily transferred back to Xinjiang, where their safety cannot necessarily be guaranteed,” it said.

An Apple spokesman, Josh Rosenstock, told the Washington Post: “Apple is dedicated to ensuring that everyone in our supply chain is treated with the dignity and respect they deserve. We have not seen this report but we work closely with all our suppliers to ensure our high standards are upheld.”

A Volkswagen spokesman told the paper: “None of the mentioned supplier companies are currently a direct supplier of Volkswagen.” He said: “We are committed to our responsibility in all areas of our business where we hold direct authority.”

A Nike spokeswoman told the Post: “We are committed to upholding international labour standards globally,” adding that its suppliers are “strictly prohibited from using any type of prison, forced, bonded or indentured labour”. Kim Jae-min, the chief executive of Taekwang, the QingdaoTaekwang factory’s South Korean parent company, said about 600 Uighurs were among 7,100 workers at the plant, adding that the migrant workers had been brought in to offset local labour shortages.

The above article is proof that just banning products made in Xinjiang, Tibet and other minority areas is not enough. The Chinese government is moving Uyghur, Tibetan and other minority areas' people to other parts of China to work as slaves in factories that make products for big brand name corporations like Nike and Apple. These international corporations are complicit by looking the other way for access to cheap Chinese slave labor. The only way to stop forced slave labor in China is if these big international corporations move all their manufacturing out of China.

At least 80,000 Uighurs working under ‘conditions that strongly suggest forced labour’

At least 80,000 Uighurs have been transferred from Xinjiang province, some of them directly from detention centres, to factories across China that make goods for dozens of global brands, according to a report from the Canberra-based Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

Using open-source public documents, satellite imagery, and media reports, the institute identified 27 factories in nine Chinese provinces that have used labourers transferred from re-education centres in Xinjiang since 2017 as part of a programme known as “Xinjiang aid”.

In conditions that “strongly suggest forced labour”, the report says, workers live in segregated dormitories, are required to study Mandarin and undergo ideological training. They are frequently subjected to surveillance and barred from observing religious practices. According to government documents analysed by the ASPI, workers are often assigned minders and have limited freedom of movement.

The factories were part of supply chains providing goods for 83 global brands, the report found, including Apple, Nike and Volkswagen among others.

China has come under mounting international scrutiny for its policies toward Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, where as many as 1.5 million people have been sent to re-education and internment camps. Beijing, which says these facilities are voluntary vocational training centres, has said in recent months that most “students” of such centres have “graduated” and returned to society.

The report from the ASPI adds to growing evidence that even after being released from the camps, former detainees are still subject to severe controls and in some cases forced labour. The report’s authors said the actual number of those sent to other parts of China as part of the work programme was “likely to be far higher” than 80,000.

“This report exposes a new phase in China’s social re-engineering campaign targeting minority citizens, revealing new evidence that some factories across China are using forced Uighur labour under a state-sponsored labour transfer scheme that is tainting the global supply chain,” the researchers concluded.

Case studies highlighted in the report, titled Uyghurs for Sale, include Qingdao Taekwang Shoes, a factory in eastern China that produces shoes for Nike. The workers were mostly Uighur women from the prefectures of Hotan and Kashgar in southern Xinjiang, and attended night classes whose curriculum was similar to that of the re-education camps.

According to government notices, workers were required to attend the “Pomegranate Seed” night school, named after a policy that aims to make ethnic minorities and the majority Han Chinese ethnic group as close as the seeds of a pomegranate. At the school, workers study Mandarin, sing the Chinese national anthem and receive “patriotic education”. Public security and other government workers were to give daily reports on the “thoughts” of the Uighur workers.

Advertisements for “government-sponsored Uighur labour” have begun to appear more frequently online, according to the researchers. One ad read: “The advantages of Xinjiang workers are: semi-military style management, can withstand hardship, no loss of personnel … minimum order 100 workers!”

The report called on China to allow multinational companies unfettered access to investigate any potential instances of abusive or forced labour in factories in China, and for companies to conduct audits and human rights due-diligence inspections.

“It is vital that, as these problems are addressed, Uighur labourers are not placed in positions of greater harm or, for example, involuntarily transferred back to Xinjiang, where their safety cannot necessarily be guaranteed,” it said.

An Apple spokesman, Josh Rosenstock, told the Washington Post: “Apple is dedicated to ensuring that everyone in our supply chain is treated with the dignity and respect they deserve. We have not seen this report but we work closely with all our suppliers to ensure our high standards are upheld.”

A Volkswagen spokesman told the paper: “None of the mentioned supplier companies are currently a direct supplier of Volkswagen.” He said: “We are committed to our responsibility in all areas of our business where we hold direct authority.”

A Nike spokeswoman told the Post: “We are committed to upholding international labour standards globally,” adding that its suppliers are “strictly prohibited from using any type of prison, forced, bonded or indentured labour”. Kim Jae-min, the chief executive of Taekwang, the QingdaoTaekwang factory’s South Korean parent company, said about 600 Uighurs were among 7,100 workers at the plant, adding that the migrant workers had been brought in to offset local labour shortages.

The above article is proof that just banning products made in Xinjiang, Tibet and other minority areas is not enough. The Chinese government is moving Uyghur, Tibetan and other minority areas' people to other parts of China to work as slaves in factories that make products for big brand name corporations like Nike and Apple. These international corporations are complicit by looking the other way for access to cheap Chinese slave labor. The only way to stop forced slave labor in China is if these big international corporations move all their manufacturing out of China.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-muslims-detention-centers-xinjiang-crackdown/2020/09/23/44d2ce50-f32b-11ea-8025-5d3489768ac8_story.html

China is building vast new detention centers for Muslims in Xinjiang

A huge Brutalist entrance gate, topped with the red national flag, stands before archetypal Chinese government buildings. There is no sign identifying the complex, only an inscription bearing an exhortation from Communist Party founding father Mao Zedong: "Stay true to our founding mission and aspirations."

But the 45-foot-high walls and guard towers indicate that this massive compound — next to a vocational training school and a logistics center south of Kashgar — is not just another bureaucratic outpost in western China, where authorities have waged sweeping campaigns of repression against the mostly Muslim Uighur minority.

It is a new detention camp spanning some 60 acres, opened as recently as January. With 13 five-story residential buildings, it can accommodate more than 10,000 people.

The Kashgar site is among dozens of prisonlike detention centers that Chinese authorities have built across the Xinjiang region, according to the Xinjiang Data Project, an initiative of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), despite Beijing's claims that it is winding down its internationally denounced effort to "reeducate" the Uighur population after deeming the campaign a success.

A recent visit to Xinjiang by The Washington Post and evidence compiled by ASPI, a Canberra-based think tank, suggest international pressure and outrage have done little to slow China's crackdown, which appears to be entering an ominous new phase.

For the past year, the Chinese government has said that almost all the people in its "vocational training program" in Xinjiang, ostensibly aimed at "deradicalizing" the region's mostly Muslim population, had "graduated" and been released into the community.

"This shows that the statements made by the government are patently false," said ASPI researcher Nathan Ruser, adding that there had merely been a "shift in style of detention."

'Prisons by another name'

The new compound, one of at least 60 facilities either built from scratch or expanded over the past year, has floodlights and five layers of tall barbed-wire fences in addition to the towering walls.

Satellite imagery reveals a tunnel for sending detainees from a processing center into the facility, and a large courtyard like those seen in other camps where detainees have been forced to pledge allegiance to the Chinese flag.

"This is a much more concerted effort to detain and physically remove people from society," Ruser said. "There aren't any sort of rehabilitative features in these higher-security detention centers. They seem to rather just be prisons by another name."

Some prison-style facilities like the one outside Kashgar are new. Other existing sites have been expanded with higher-security areas. New buildings added to Xinjiang's largest camp, in Dabancheng, near Urumqi, last year stretched to almost a mile in length, Ruser said.

Some 14 facilities are still being built across Xinjiang, the satellite imagery shows.