- Joined

- Nov 10, 2020

- Messages

- 12,207

- Likes

- 73,694

Strabo - The Custom duties on the BHARTIYA commodities

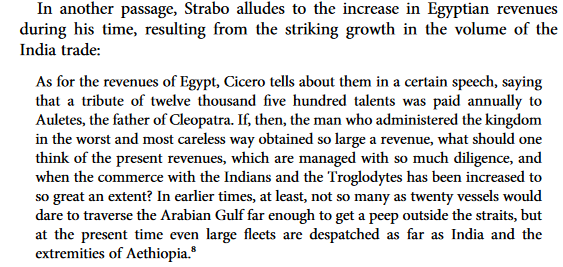

Strabo visited Egypt soon after the Roman conquest, when his friend Aelius Gallus was prefect—sometime between 27 and 24 .¹ Although what he learnt about the recent developments of the India trade had basically no impact on his description of India in the fifteenth book of the Geography, his passing remarks on the subject—coming from a man who was privy to the operation of the Roman government of Egypt and well versed in the historical and geo- graphic literature—are extremely interesting and command close attention.

For instance, Strabo notes: that while he was accompanying Aelius Gallus on his voyage to Syene (probably in 26 ), as many as 120 ships had left from Myos Hormos;² that in recent years (νυνί) Indian and Arabian commodities reached the Mediterranean via the Myos Hormos–Coptos–Alexandria route.

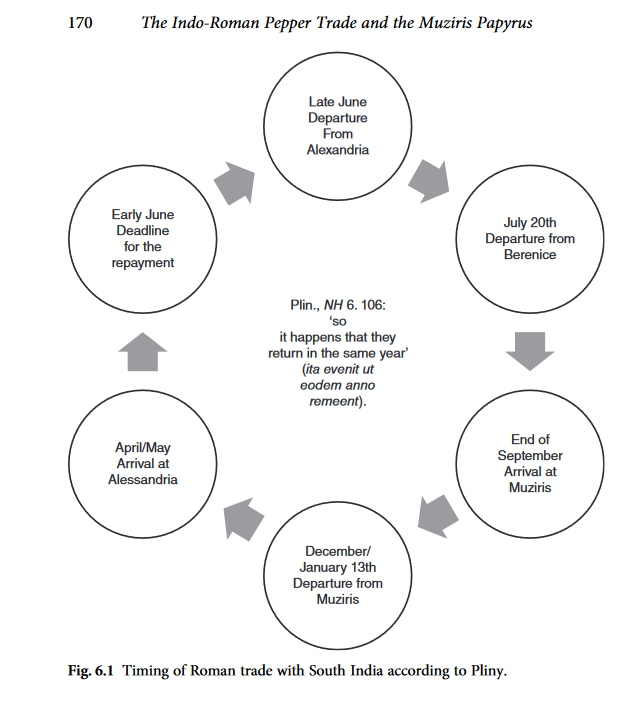

Pliny - The Timetable of the Commercial Enterprises to the southern BHARAT

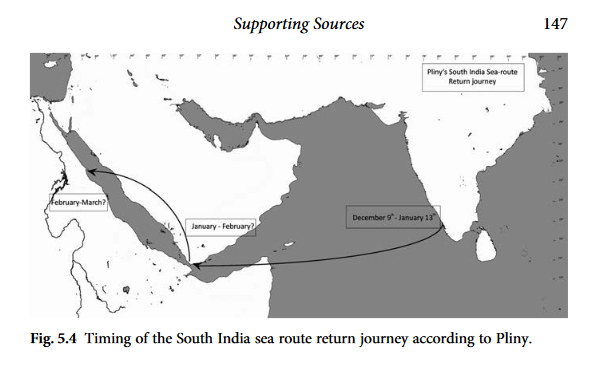

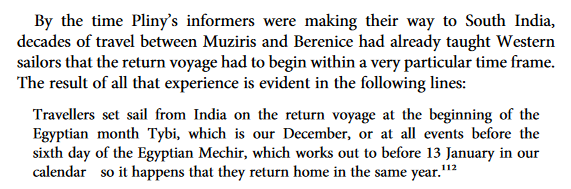

Pliny’s account begins with a reiteration of Alexander’s travels from Pataleto Susa.⁹⁰ He then records two older sea routes, both of which depart from the South Arabian promontory of Syagrus, and reach Patale and Sigerum, respectively.⁹¹ Finally, he adds the full description of the contemporaneous Alexandria–Muziris–Alexandria sea route.⁹² Pliny emphasizes that it was worthwhile chronicling the entire voyage in detail, because it was only in his own time that solid information became public knowledge.⁹³ In fact, com-

pared to what Strabo had assembled in his fifteenth book, Pliny’s chapter on the South India trade seems ground-breaking.

Unlike the author of the Periplus, Pliny does not specify the size of the vessels bound for South India, but two details in his account corroborate the statement in the Periplus regarding their large size.

Pliny designates Muziris as the ‘first emporion of India’.

Ptolemy - The Evolution of the Southern BHARTIYA Context

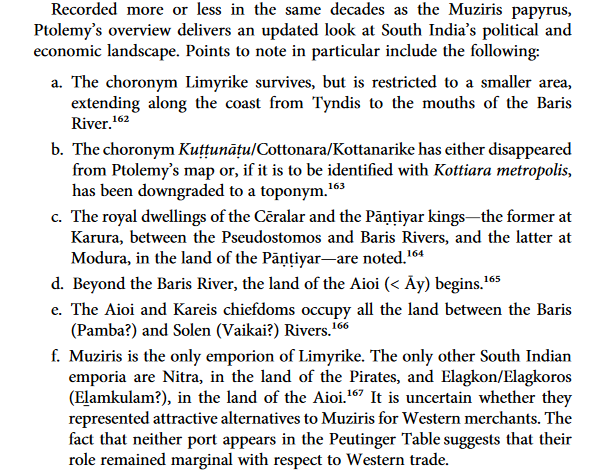

In Ptolemy’s world map, the Indian subcontinent looks so different from the shape we are familiar with that we would hardly recognize it, if it were sketched without the Indus and Ganges Rivers (Fig. 5.6). By contrast, the Arabian and even the Malay peninsulas are not too badly rendered. Yet Ptolemy provides an extremely detailed inventory of India’s geography, with an extraordinary number of place names and locations.

That said, it has to be emphasized that despite these flaws, the pertinent sections of Ptolemy’s Geography are the most eloquent testament to (and meagre compensation for) the now-lost geographical works on South India that were written in the first and early second centuries .¹⁶

When contrasted with the information from the Periplus, Pliny, and ancient Tamil literature, these data give a sense of the evolution of South India’s political and commercial milieux. In the first century , the Pā :nṭ iyar competed with the Cēralar for control over the entire Kuṭ ṭanāṭu region,¹⁶⁸ and their emporion of Bakare/Nelkynda—rich, safe, and convenient—challenged Muziris’ commercial primacy. By the time of Pliny, Bakare/Nelkynda had become so attractive that it was recommended over Muziris. Later on, it was

the Cēralar who became the masters of the Kuṭṭ anāṭ u region. Palyāṉaic Celkeḻ u Kuṭ ṭ uvaṉ, hero of the third decade of Patiṟ ṟuppattu, may have been the first Cēra king to be hailed as Kuṭṭ uvaṉ (Lord of Kuṭ ṭ anāṭ u) by poets.¹⁶⁹ Since some portion of the fifty-year reign of his nephew Kaṭ al Piṟ akōṭ ṭ iya

Ce : nkuṭ ṭ uvaṉ, hero of the fifth decade of Patiṟ ṟuppattu, may have coincided with a part of the twenty-two year reign of Gajabāhu in Sri Lanka in the second half of the second century ,¹⁷⁰ we may suggest that the twenty years of Palyāṉaic Celkeḻ u Kuṭ ṭ uvaṉ’s (co-?)reign may date to the first half of the

second century .¹⁷¹

Strabo visited Egypt soon after the Roman conquest, when his friend Aelius Gallus was prefect—sometime between 27 and 24 .¹ Although what he learnt about the recent developments of the India trade had basically no impact on his description of India in the fifteenth book of the Geography, his passing remarks on the subject—coming from a man who was privy to the operation of the Roman government of Egypt and well versed in the historical and geo- graphic literature—are extremely interesting and command close attention.

For instance, Strabo notes: that while he was accompanying Aelius Gallus on his voyage to Syene (probably in 26 ), as many as 120 ships had left from Myos Hormos;² that in recent years (νυνί) Indian and Arabian commodities reached the Mediterranean via the Myos Hormos–Coptos–Alexandria route.

Pliny - The Timetable of the Commercial Enterprises to the southern BHARAT

Pliny’s account begins with a reiteration of Alexander’s travels from Pataleto Susa.⁹⁰ He then records two older sea routes, both of which depart from the South Arabian promontory of Syagrus, and reach Patale and Sigerum, respectively.⁹¹ Finally, he adds the full description of the contemporaneous Alexandria–Muziris–Alexandria sea route.⁹² Pliny emphasizes that it was worthwhile chronicling the entire voyage in detail, because it was only in his own time that solid information became public knowledge.⁹³ In fact, com-

pared to what Strabo had assembled in his fifteenth book, Pliny’s chapter on the South India trade seems ground-breaking.

Unlike the author of the Periplus, Pliny does not specify the size of the vessels bound for South India, but two details in his account corroborate the statement in the Periplus regarding their large size.

Pliny designates Muziris as the ‘first emporion of India’.

Ptolemy - The Evolution of the Southern BHARTIYA Context

In Ptolemy’s world map, the Indian subcontinent looks so different from the shape we are familiar with that we would hardly recognize it, if it were sketched without the Indus and Ganges Rivers (Fig. 5.6). By contrast, the Arabian and even the Malay peninsulas are not too badly rendered. Yet Ptolemy provides an extremely detailed inventory of India’s geography, with an extraordinary number of place names and locations.

That said, it has to be emphasized that despite these flaws, the pertinent sections of Ptolemy’s Geography are the most eloquent testament to (and meagre compensation for) the now-lost geographical works on South India that were written in the first and early second centuries .¹⁶

When contrasted with the information from the Periplus, Pliny, and ancient Tamil literature, these data give a sense of the evolution of South India’s political and commercial milieux. In the first century , the Pā :nṭ iyar competed with the Cēralar for control over the entire Kuṭ ṭanāṭu region,¹⁶⁸ and their emporion of Bakare/Nelkynda—rich, safe, and convenient—challenged Muziris’ commercial primacy. By the time of Pliny, Bakare/Nelkynda had become so attractive that it was recommended over Muziris. Later on, it was

the Cēralar who became the masters of the Kuṭṭ anāṭ u region. Palyāṉaic Celkeḻ u Kuṭ ṭ uvaṉ, hero of the third decade of Patiṟ ṟuppattu, may have been the first Cēra king to be hailed as Kuṭṭ uvaṉ (Lord of Kuṭ ṭ anāṭ u) by poets.¹⁶⁹ Since some portion of the fifty-year reign of his nephew Kaṭ al Piṟ akōṭ ṭ iya

Ce : nkuṭ ṭ uvaṉ, hero of the fifth decade of Patiṟ ṟuppattu, may have coincided with a part of the twenty-two year reign of Gajabāhu in Sri Lanka in the second half of the second century ,¹⁷⁰ we may suggest that the twenty years of Palyāṉaic Celkeḻ u Kuṭ ṭ uvaṉ’s (co-?)reign may date to the first half of the

second century .¹⁷¹