- Joined

- Nov 10, 2020

- Messages

- 12,207

- Likes

- 73,694

Slightly adapted from the works of .

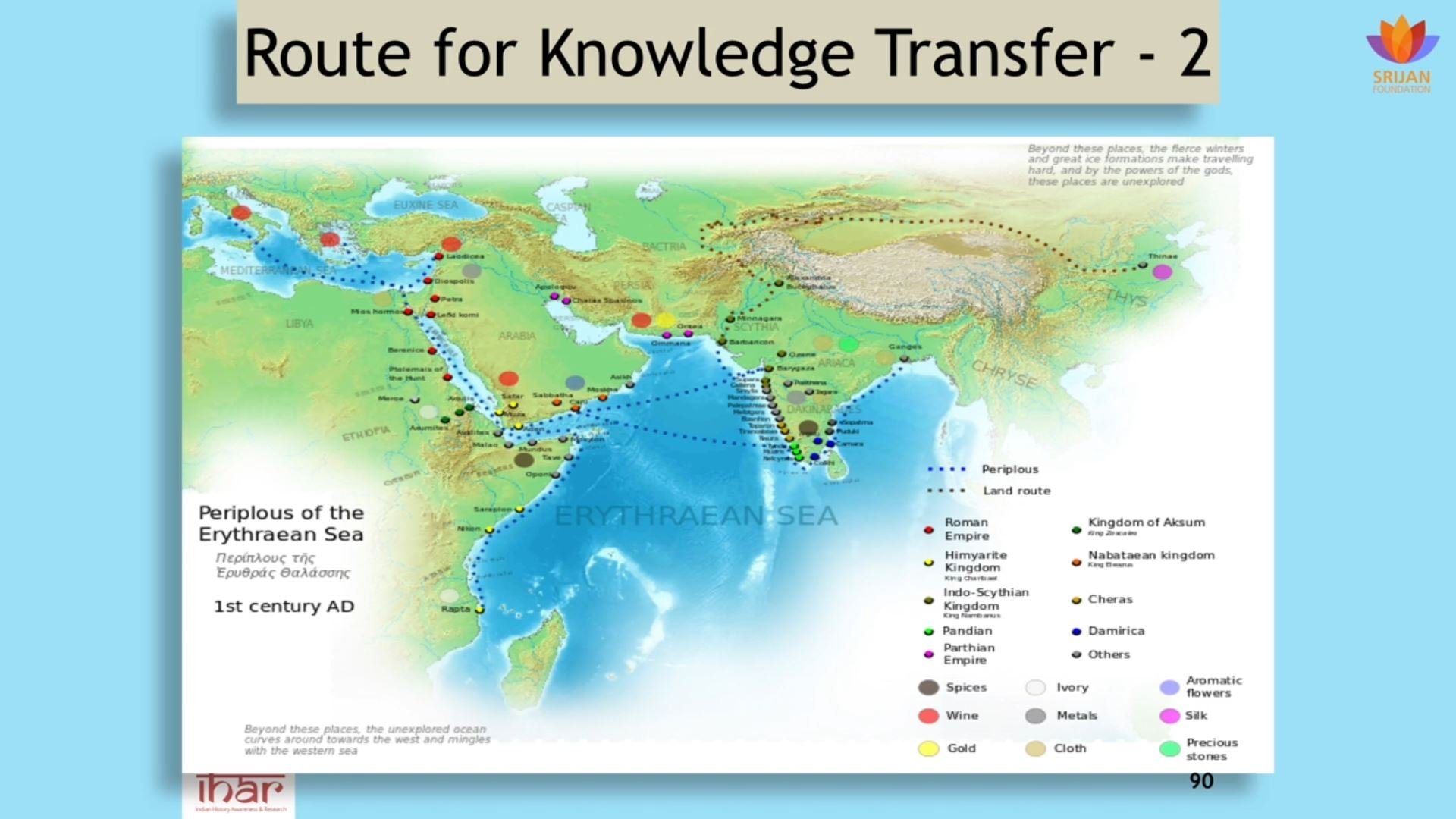

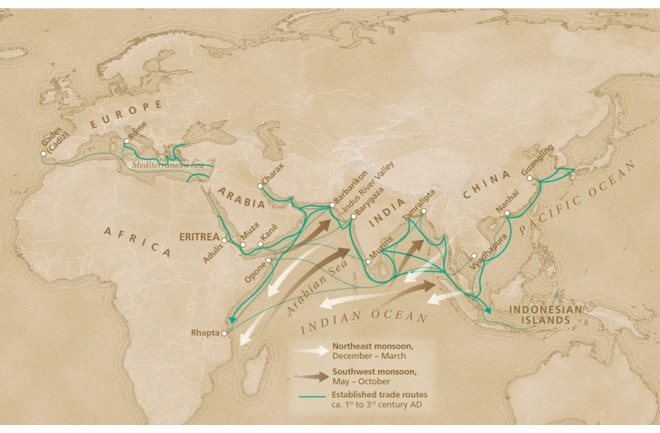

The Indo-Roman trade started in the 1st century bce, it truly matured in the 1st and 2nd centuries ce. The geographical location of Arabia, Asia Minor and northeastern Africa helped to establish trade contacts between South Asia, West Asia and Europe. As far as India is concerned, the earliest evidence of this trade is to be found from the southern Peninsula, especially in the state of Kerala. Indo- Roman trade was carried out on the sea as well on land. The seaborne trade was controlled by the Śakas and the Sātavāhanas whereas the land-borne trade was monitored by the Kuśāṇas.

The richest temple in the world in Trivandrum, Kerala where Shri Padmanabhaswamy Temple's recently discovered treasures show several boxes of roman coins amassed during such vast maritime trade.

It is believed that to promote foreign trade, Kanīṣka, the Kuṣāṇa ruler made use of the standard of the Roman gold coins for his own issues. The political tensions between the Śakas and Sātavāhanas did affect this trade for some time at least. Similarly, the contentions between the Śakas and Parthians also served as a major impediment for trade overland. In order to overcome this problem, Augustus, the Roman Emperor encouraged the traders to take the sea route and offered them protection as well.

A silver pepper pot, gemstones, black pepper, cooking pots, coins and Roman amphorae - historian Roberta Tomber chose these six seemingly disparate and unconnected objects to show why and how Indo-Roman trade was conducted in the ancient world. It was certainly carried on massive levels.

These videos basically sum up as to whatever has been posted in this thread so far.

From north of our Bharat to further in south the Cholas Cheras Pandyas all have had very extensive contacts and trading with roman empire.

Trade and contacts also happened using roadways but largely it was via seas so we will be focusing on sea based trade between romans and BHARAT.

The Indo-Roman trade started in the 1st century bce, it truly matured in the 1st and 2nd centuries ce. The geographical location of Arabia, Asia Minor and northeastern Africa helped to establish trade contacts between South Asia, West Asia and Europe. As far as India is concerned, the earliest evidence of this trade is to be found from the southern Peninsula, especially in the state of Kerala. Indo- Roman trade was carried out on the sea as well on land. The seaborne trade was controlled by the Śakas and the Sātavāhanas whereas the land-borne trade was monitored by the Kuśāṇas.

The richest temple in the world in Trivandrum, Kerala where Shri Padmanabhaswamy Temple's recently discovered treasures show several boxes of roman coins amassed during such vast maritime trade.

It is believed that to promote foreign trade, Kanīṣka, the Kuṣāṇa ruler made use of the standard of the Roman gold coins for his own issues. The political tensions between the Śakas and Sātavāhanas did affect this trade for some time at least. Similarly, the contentions between the Śakas and Parthians also served as a major impediment for trade overland. In order to overcome this problem, Augustus, the Roman Emperor encouraged the traders to take the sea route and offered them protection as well.

A silver pepper pot, gemstones, black pepper, cooking pots, coins and Roman amphorae - historian Roberta Tomber chose these six seemingly disparate and unconnected objects to show why and how Indo-Roman trade was conducted in the ancient world. It was certainly carried on massive levels.

These videos basically sum up as to whatever has been posted in this thread so far.

From north of our Bharat to further in south the Cholas Cheras Pandyas all have had very extensive contacts and trading with roman empire.

Trade and contacts also happened using roadways but largely it was via seas so we will be focusing on sea based trade between romans and BHARAT.

Last edited: