by The Diplomat

A view of the interior of the newly-constructed Lemon Tree Premier hotel, located outside the Indira Gandhi International Airport in New Delhi April 2, 2013. The cluster of hotels built here is known as Aerocity.

Image Credit: REUTERS/Adnan Abidi

Life In Aerocity: Finding India’s Place in the New Strategic Context

“India will be a leading author in the next chapter of world politics.”

Over the past three years, through periodic observations, I have measured the rise of New Delhi Aerocity, the commercial complex adjacent to Indira Gandhi International Airport. Unlike the unruly and burgeoning outskirts of this megacity – the teeming slums, clogged arteries, impromptu shrines and haphazard construction – Aerocity is sterile and organized, and,

hopefully, a secure compound of paned-glass modernity. Like its cousins, Gurgaon’s DLF Cyber City and Noida’s Jaypee Sports City, Aerocity is a planned urban-development with a specific commercial design, in this case an international business hub intended to enhance the airport’s economic engine beyond aeronautical activities, a

common characteristic of our futuristic global age.

Aerocity construction Credit: Roncevert Ganan Almond

In the shadow of the future, history always awaits in India. At Aerocity, the nearby Delhi Metro connects you to the city center, and within half an hour you can wander through Old Delhi to Kashmiri Gate, locus of the

siege of Delhi, a key battle during the Mutiny of 1857. Sometimes known as India’s First War of Independence, an event credited by Karl Marx as a national revolt, the Mutiny ushered in a new age in the history of the subcontinent and the world: the establishment of the British Raj and direct colonial rule, the beginning of an end. The Congress party – of Gokhale, Tilak, Gandhi and Nehru – would be founded a generation later. The seeds of change were planted in the reddened soil of Delhi.

With the inauguration of U.S. President Donald Trump, a revolt of sorts, a new era appears in the making once again. As

Arun Kumar Singh, the former Indian ambassador to the U.S., notes, the Trump presidency remains undefined; and it is unclear,

in my view, whether President Trump will sustain America’s global leadership. In its

report on global trends, prepared every four years for the incoming president, the U.S. National Intelligence Council (NIC) describes an international landscape in flux, as the post-Cold War, unipolar moment has passed and the rules-based international order is being subject to revision. Without a doubt, India will be a leading author in the next chapter of world politics and the Asia-Pacific will be the manuscript upon which it is written.

The new café at Aerocity, therefore, seemed like the appropriate place to consider the NIC’s findings and India’s place in the new strategic context.

Victim of Success

The period of the greatest globalization in the world economy – from 1989 to 2008 – fueled a historic rise in living standards for almost a billion people. As described by the NIC, the biggest “winners” included members of the new middle class in emerging economies, with India being an exemplary example. [Among the “losers” were lower-to-middle-income households of advanced economies, a political reality confirmed by the 2016 U.S. presidential election.]

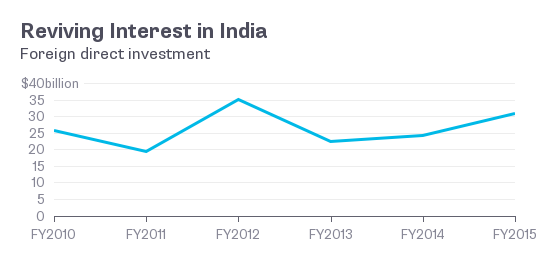

Beginning in the 1990s, India enacted liberalizing economic reforms fueling

historic growth rates that crested in 2010. The scale and speed of the growth was exceptional: India doubled its per capita income in 17 years; the United Kingdom took 154 years to perform the same feat. As a result, many of the world’s households who graduated from subsistence – living in “extreme poverty” (below $2 a day) – reside in India. And with increased wealth comes increased hope.

Among the global trends identified by the NIC is a growing distrust of governments and elites due to a widening gap between government performance and public expectations. In this vein, the rise of Narendra Modi, with his

Gujurat-model, may be interpreted as a response to India’s economic downturn in 2011 and the perceived incapability of the Congress-led coalition government. In turn, the test for the prime minister is satisfying the increasing middle class sensibilities of his electorate while addressing India’s profound structural and societal challenges.

Fortunately for South Block, the NIC predicts that India will be the world’s fastest growing economy during the next five years as China’s economy slows. At the same time, India is facing escalating demands for education and employment that accompany its rising, youthful population. According to the NIC report, India will need to create as many as 10 million jobs each year in the coming decades to meet new demand in the workforce. In the meantime, disruptive technologies like artificial intelligence and increased automation could eliminate jobs and place India in a

middle-income trap. Insufficient opportunity may lead to radicalization of the country’s bulging youth.

For example, in search of meaning and identity, disaffected youth could turn to religious and ethnic identity, which in India, despite its worthy efforts at promoting tolerance, could mean sharpened communal divisions. Recent

protests in Chennai, the country’s fourth largest metropolitan area, asserting Tamil culture may be evidence of this phenomena. Moreover, India is projected to surpass Indonesia as having the world’s largest Muslim population in 2050. In the words of the NIC:

“The perceived threat of terrorism and the idea that Hindus are losing their identity in their homeland have contributed to the growing support for Hindutva, sometimes with violent manifestations and terrorism. India’s largest political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, increasingly is leading the government to incorporate Hindutva into policy, sparking increased tension in the current sizable Muslim minority as well as with Muslim-majority Pakistan and Bangladesh.”

Added to this dynamic is the problem of widespread prenatal sex selection. The NIC projects that within 20 years, large parts of India will have 10 to 20 percent more men than women. Such societal imbalances – which take decades to mitigate – have been linked to abnormal levels of crime and human rights violations such as rape, human trafficking and sexual exploitation. Even if anecdotal,

newspaper headlines of sexual violence, on any given day in Delhi, is a black and white reminder of this problem.

In sum, the NIC warns that India could become a “victim of its own success” as the country’s growing prosperity leads to a “paradox of progress” where effective governance runs into the complications of the youth bulge, rapid urbanization, inadequate infrastructure, poor public health, severe environmental degradation, and exclusionary identity politics. Nowhere is this dynamic more evident than in India’s megacities.

Megacity Mania

By 2035, the NIC forecasts that more than three-fifths of the world’s population will live in urban areas, an approximate 7-percentage point increase from 2016. This means that an overwhelming majority of the world’s projected population of 8.8 billion (a 20 percent increase from today) will reside in cities. By this time India will have become the world’s most populous country with 1.5 billion people, almost half of whom (42.1 percent) will be urban dwellers; the subcontinent may have three of the world’s 10 biggest cities and 10 of its top 50.

The challenge of megacities (measured at 10 million or more) is enormous. Again from the NIC report:

“Although megacities often contribute to national economic growth, they also spawn sharp contrasts between rich and poor and facilitate the forging of new identities, ideologies, and movements. South Asia’s cities are home to the largest slums in the world, and growing awareness of the economic inequality they exemplify could lead to social unrest. As migrants from poorer regions move to areas with more opportunities, competition for education, employment, housing, or resources may stoke existing ethnic hatred, as has been the case in parts of India.”

As Katherine Boo so

memorably recorded, slums like Annawadi, adjacent to Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport, are scenes of intense human drama and immense tragedy. Slums can also overwhelm the capacity of local governments. From Google Earth you can see how Mumbai’s slums have altered the symmetry of the airport layout, with

one arm of Terminal 2 stunted to account for the protruding tent city. These slums present a

unique security threat, providing potential access for terrorists seeking to capitalize on the high-visibility and strategic value of Mumbai’s airport.

And with rising urbanization comes increased pollution. The NIC reports that South Asia already has 15 of the world’s 25 most polluted cities, and more than 20 cities in India alone have air quality worse than Beijing’s. By 2035, air pollution is projected to be the top cause of environmentally related deaths worldwide. The incredible levels of Delhi’s air pollution already alter the daily lives and life spans of its citizens.

Traffic on Delhi’s beltways – a snarling slow-moving parade of two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and four-wheelers (in addition to the occasional horse-drawn cart) – leaves one bleary-eyed and sniffling. Many days the

air quality index (AQI) is “hazardous,” meaning that conditions causing “serious aggravation of heart or lung disease and premature mortality in persons with cardiopulmonary disease and the elderly” and “serious risk of respiratory effects in general population.” In order to curb pollution, the

Supreme Court has intervened to enforce an odd-even system wherein daily vehicle-use is segregated based on license plate numbers.

These new urban centers also serve as hotbeds for religious movements. For example, the NIC categorizes India’s Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, as a “predominantly urban phenomenon.” In support, the report cites Shiv Sena – the most radical Hindutva political party – which has governed Mumbai for several decades. The future could see growing support for sectarian elements and the potential for violence in efforts to enforce cultural homogeneity in the community. For India, which still has fresh scars from Partition, this is not an idle threat. To borrow from Shiv Visvanathan, the “

silences of Partition” could give rise to new and unpredictable voices. In measuring norms of democracy and tolerance, the NIC cautions that the world will look to see how India “tames its Hindu nationalist impulses.” Given India’s civilizational influence, the most attentive audience will be its neighbors.

Limited War, Unlimited Consequences

Since its founding modern India has struggled with securing its periphery – the frontier arch extending from the headwaters and tributaries of the Indus River to those of the Brahmaputra. In turn, India’s national security policy has focused on the immediate threat from Pakistan, volatility in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, and a lurking China peering over the Himalayas.

The NIC counsels that Pakistan, unable to match India’s economic prowess, will seek other methods to maintain even a “semblance of balance.” The risk of conflict with Pakistan must be understood within a greater trend toward interstate conflict due to diverging interests among major powers, ongoing terrorist threats, continued instability in weak states, and the spread of lethal and disruptive technologies. According to the NIC report:

“Future conflicts will increasingly emphasize the disruption of critical infrastructure, societal cohesion, and basic government functions in order to secure psychological and geopolitical advantages, rather than the defeat of enemy forces on the battlefield through traditional military means.”

Weaker parties may resort to asymmetric warfare and surrogate attacks, a form of limited war, but with the potential for unlimited consequences in the case of nuclear-armed India and Pakistan.

Indeed, New Delhi has struggled with finding the balance between “confrontation” and “engagement” with Islamabad, to paraphrase Srinath Raghavan in his keen contribution to

Shaper Nations. In 2016 we witnessed a re-occurrence of this dynamic in Kashmir. India accused Pakistan of supporting incursions over the Line of Control (LOC), including by Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, a designated terrorist organization. In turn, New Delhi allegedly engaged in “surgical strikes” against Pakistani forces in Kashmir. Most recently, Modi

signaled the terms for future engagement: “Pakistan must walk away from terror if it wants to walk towards dialogue with India.” The subcontinent’s security dilemma, however, may not allow for such tightrope finesse.

The blurring of war and peace in South Asia may lead to potentially catastrophic violence. The NIC report predicts that Pakistan will seek to develop a credible nuclear deterrent by expanding its nuclear arsenal and delivery means, including short-range, “battlefield” nuclear weapons and a sea-based option, which lower the threshold for nuclear use. In one of its future mock scenarios, the NIC forecasts a “mushroom cloud in a desert in South Asia” – a nuclear exchange between Delhi and Islamabad – the first nuclear conflict since 1945.

In a more positive frame, the NIC tributes India with being the region’s “greatest hope” to drive regional trade and development. As part of a broader effort to assert its role as the predominant regional power, the NIC predicts that New Delhi will expand its orbit by offering neighboring countries – Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Burma – a stake in India’s economic growth through development assistance and increased connectivity to India’s economy. In Afghanistan, New Delhi has sought to foster a

direct and productive relationship, having spent more than $2 billion on economic cooperation.

For China relations, the picture is complex. India must carry the burden of having an irredentist great power on its northern border. New Delhi is still recovering from shock of the 1962 war. Despite Indian objections, China is continuing to build the

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which passes through Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. According to the NIC, China’s actions and indifference for India’s interests are driving New Delhi’s to balance and hedge. The strain in the bilateral relationship is further aggravated by Beijing’s position in world governing bodies.

Seat at the Table

Unsurprisingly India is seeking an expanded role in international institutions to match its increasing presence on the world stage. For example, New Delhi would like a

permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and

membership in the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), a club of countries that contributes to non-proliferation by controlling access to nuclear technology. This is consistent with the NIC’s finding that states, in an attempt to gain new privileges, will seek to adjust the hierarchy in existing institutions.

New Delhi is growing

increasingly frustrated with Beijing’s blocking of India’s seat at the table of global governance. However, necessary reform of international institutions to reflect a new distribution of power is unlikely given conflicting interests among member states. The NIC foresees the exercise of veto power by key players:

“Competing interests among major and aspiring powers will limit formal international action in managing disputes, while divergent interests among states in general will prevent major reforms of the UN Security Council’s membership. Many agree on the need to reform the UN Security Council, but prospects for consensus on membership reform are dim.”

During this struggle, international norms and institutions may stagnate and decay.

Joseph Nye warns that the U.S. may turn inward with a corresponding loss in global public goods. The global community may lose what my graduate professor

Bob Keohane described as gains in cooperation, efficiency and interdependence from regimes developed over the course of the last century. A devolvement to regional bodies, spheres of influence, and improvised crisis-management will create new costs and uncertainty.

One result of this 21st century disorder will be the strengthening of U.S.-India relations. The NIC characterizes India as “an increasingly important factor in the region as geopolitical forces begin to reshape its importance to Asia” and predicts that the United States and India “will grow closer than ever in their history.” Some of the foreign policy landmarks of former U.S. President Barack Obama’s legacy reflect this convergence: his announcement of U.S. support for India’s permanent UNSC seat; the decoupling of Pakistan from the U.S.-India relationship; and the U.S. backing of Delhi’s inclusion in the NSG despite earlier conflict related to nuclear proliferation. Indeed, India and the United States, as the world’s two largest democracies, will be key architects for

building a future based on liberal values related to civil, political, and human rights.

A State of Motion

India faces significant challenges in moving forward to achieve its full potential. As the NIC observes, the country sits at the vanguard of global trends related to world trade, urbanization, environmental impact, terrorism, inter-state conflict, religious identity, and international governance. India must be prepared to shape its destiny, not be a passive participant in its “

tryst with destiny.” The future of world politics requires an active and assertive India.

Much like with the geopolitical landscape, construction continues here in Aerocity. Laborers, migrants from dry villages of the Gangetic plane and abandoned Himalayan hill stations, new megacity residents, enter each day to realize the promise of 21st century India. Swaying cranes, swinging shovels, rumbling bulldozers, Aerocity is in constant motion, kicking dust into the air, another layer in the fog above Delhi. When the jackhammer pauses, I put down the NIC report and look upward, in search of the sky.