Direct Evidences from Sanskrit and Pali Literature.

It has been already pointed out that though Sanskrit and Pali literature abounds in references to the trading voyages of Indians, they unfortunately furnish but few references having a direct bearing on the ships and shipbuilding of India which enabled her to keep up her international connections. I have, however, been able to find one Sanskrit work,[which is something like a treatise on the art of shipbuilding in ancient India, setting forth many interesting details about the various sizes and kinds of ships, the materials out of which they were built, and the like; and it sums Up in a condensed form all the available information and knowledge about that truly ancient industry of India. The book requires a full notice, and its contents have to be explained.

The ancient shipbuilders had a good knowledge of the materials as well as the varieties and properties of wood which went to the making of ships. According to the

Vṛiksha-Āyurveda, or the Science of Plant Life (Botany), four different kinds of wood are to be distinguished: the first or the Brahman class comprises wood that is light and soft and can be easily joined to any other kind of wood; the second or the Kshatriya class of wood is light and hard but cannot be joined on to other classes; the wood that is soft and heavy belongs to the third or Vaisya class; while the fourth or the Sudra class of wood is characterized by both hardness and heaviness. There may also be distinguished wood of the mixed (Dvijāti) class, in which are blended properties of two separate classes.

According to Bhoja, an earlier authority on shipbuilding, a ship built of the Kshatriya class of wood brings wealth and happiness.

It is these ships that are to be used as means of communication where the communication is difficult owing to vast water. Ships, on the other hand, which are made of timbers of different classes possessing contrary properties are of no good and not at all comfortable. They do not last for a long time, they soon rot in water, and they are liable to split at the slightest shock and to sink down.

Besides pointing out the class of wood which is best for ships, Bhoja also lays down a very important direction for shipbuilders in the nature of a warning which is worth carefully noting.

[6] He says that care should be taken that no iron is used in holding or joining together the planks of bottoms intended to be sea-going vessels, for the iron will inevitably expose them to the influence of magnetic rocks in the sea, or bring them within a magnetic field and so lead them to risks. Hence the planks of bottoms are to be fitted together or mortised by means of substances other than iron. This rather quaint direction was perhaps necessary in an age when Indian ships plied in deep waters on the main.

Besides Bhoja's classification of the kinds of wood used in making ships and boats, the Yuktikalpataru gives an elaborate classification of the ships themselves, based on their size. The primary division[7] is into two classes: (a) Ordinary (Sāmānya): ships that are used in ordinary river traffic or waterways fall under this class; (b) Special (Viśesa), comprising only sea-going vessels. There are again enumerated ten different kinds of vessels under the Ordinary class which all differ in their lengths, breadths, and depths or heights. Below are given their names and the measurements of the three dimensions[8]:—

(

a) Ordinary.

| | Names. | Length

in cubits. | Breadth

in cubits. | Height

in cubits. |

| (1) | Kshudrā | 16 | 4 | 4 |

| (2) | Madhyamā | 24 | 12 | 8 |

| (3) | Bhīmā | 40 | 20 | 20 |

| (4) | Chapalā | 48 | 24 | 24 |

| (5) | Patalā | 64 | 32 | 32 |

| (6) | Bhayā | 72 | 36 | 36 |

| (7) | Dīrghā | 88 | 44 | 44 |

| (8) | Patraputā | 96 | 48 | 48 |

| (9) | Garbharā | 112 | 56 | 56 |

| (10) | Mantharā | 120 | 60 | 60 |

Of the above ten different kinds of

Ordinary ships the Bhīmā, Bhayā and Garbharā are liable to bring ill-luck, perhaps because their dimensions do not make them steady and well-balanced on the water.

Ships that fall under the class

Special are all sea-going.

[9] They are in the first instance divided into two sub-classes

[10]: (1) Dīrghā (दीर्घा), including ships which are probably noted for their length, and (2) Unnatā (उन्नता), comprising ships noted more for their height than their length or breadth. There are again distinguished ten varieties of ships of the Dīrghā (दीर्घा) class and five of the Unnatā (उन्नता) class. Below are given their names and the measurements

[11] of their respective lengths, breadths, and heights:—

(

b) Special.

I. Dīrghā, 42 (length), 514 (breadth), 415 (height):

| | Names. | Length. | Breadth. | Height. |

| (1) | Dīrghikā | 32 | 4 | 315 |

| (2) | Taraṇī | 48 | 6 | 445 |

| (3) | Lolā | 64 | 8 | 625 |

| (4) | Gatvarā | 80 | 10 | 8 |

| (5) | Gāminī | 96 | 12 | 925 |

| (6) | Tarī | 112 | 14 | 1115 |

| (7) | Jaṅghālā | 128 | 16 | 1245 |

| (8) | Plābinī | 144 | 18 | 1425 |

| (9) | Dhāriṇī | 160 | 20 | 16 |

| (10) | Beginī | 176 | 22 | 1735 |

Of these ten varieties of Dīrghā (दीर्घा) ships, those that bring ill-luck

[12] are Lolā (लोला), Gāminī (गामिनी), and Plābinī (प्लाविनी), and also all ships that fall between these three classes and their next respective classes.

II. Unnatā

[13] (उन्नता):

I. Dīrghā, 42 (length), 514 (breadth), 415 (height):

| | Names. | Length. | Breadth. | Height. |

| (1) | Ūrddhvā | 32 | 16 | 16 |

| (2) | Anūrddhvā | 48 | 24 | 24 |

| (3) | Svarṇamukhī | 64 | 32 | 32 |

| (4) | Garbhiṇī | 80 | 40 | 40 |

| (5) | Mantharā | 96 | 48 | 48 |

Of these five varieties, Anūrddhvā (अनूर्द्ध्वा), Garbhiṇī (गर्भिणी), and Mantharā (मन्थरा) bring on misfortune, and Ūrddhvā much gain or profit to kings.

The

Yuktikalpataru also gives elaborate directions for decorating and furnishing ships so as to make them quite comfortable to passengers. Four kinds of metal are recommended for decorative purposes, viz. gold, silver, copper, and the compound of all three. Four kinds of colours are recommended respectively for four kinds of vessels: a vessel with four masts is to be painted white, that with three masts to be painted red, that with two masts is to be a yellow ship, and the one-masted ship must be painted blue. The prows of ships admit of a great variety of fanciful shapes or forms: these comprise the heads of lion, buffalo, serpent, elephant, tiger, birds such as the duck, peahen or parrot, the frog, and man, thus arguing a great development of the art of the carpenter or the sculptor. Other elements of decoration are pearls and garlands of gold to be attached to and hung from the beautifully shaped prows.

[14]

There are also given interesting details about the cabins of ships. Three classes

[15] of ships are distinguished according to the length and position of their cabins. There are firstly the Sarbamandirā (सर्ब्बमन्दिरा) vessels, which have the largest cabins extending from one end of the ship to the other.

[16] These ships are used for the transport of royal treasure, horses, and women.

[17] Secondly, there are the Madhyamandirā (मध्यमन्दिरा) vessels,

[18] which have their cabins just in the middle part. These vessels are used in pleasure trips by kings, and they are also suited for the rainy season. Thirdly, ships may have their cabins towards their prows, in which case they will be called Agramandirā

[19] (अग्रमन्दिरा). These ships are used in the dry season after the rains have ceased. They are eminently suited for long voyages and also to be

used in naval warfare.

[20] It was probably in these vessels that the first naval fight recorded in Indian literature was fought, the vessel in which Tugra the Ṛishi king sent his son Bhujyu against some of his enemies in the distant island, who, being afterwards shipwrecked with all his followers on the ocean, "where there is nothing to give support, nothing to rest upon or cling to," was rescued from a watery grave by the two Asvins in their hundred-oared galley.

[21] It was in a similar ship that the righteous Paṇdava brothers escaped from the destruction planned for them, following the friendly advice of kind-hearted Vidura, who kept a ship ready and constructed for the purpose, provided with all necessary machinery and weapons of war, able to defy hurricanes.

[22] Of the same description were also the five hundred ships mentioned in the

Rāmāyaṇa,

[23] in which hundreds of Kaivarta young men are asked to lie in wait and obstruct the enemy's passage. And, further, it was in these ships that the Bengalis once made a stand against the invincible prowess of Raghu as described in

Kālidāsa's Raghuvańsa, who retired after planting the pillars of his victory on the isles of the holy Ganges.

[24]

The conclusions as to ancient Indian ships and shipping suggested by these evidences from Sanskrit literature directly bearing on them are also confirmed by similar evidences culled from the Pali literature. The Pali literature, like the Sanskrit, also abounds with allusions to sea voyages and sea-borne trade, and it would appear that the ships employed for these purposes were of quite a large size. Though indeed the Pali texts do not usually give the actual measurements of the different dimensions of ships such as the Sanskrit texts furnish, still they make definite mention of the number of passengers which the ships carried, and thus enable us in another very conclusive way to have a precise idea of their size. Thus, according to the

Rājavalliya, the ship in which Prince Vijaya and his followers were sent away by King Sińhaba (Sińhavāhu) of Bengal was so large as to accommodate full seven hundred passengers, all Vijaya's followers.

[25] Their wives and children, making up more than seven hundred, were also cast adrift in similar ships.

[26] The ship in which the lion-prince, Sińhala, sailed from some unknown part of Jambudvīpa to Ceylon contained five hundred merchants besides himself.

[27] The ship in which Vijaya's Pandyan bride was brought over to Ceylon was also of a very large size, for she is said to have carried no less than 800 passengers on board.

[28] The

Janaka-Jātaka mentions a ship that was wrecked with all its crew and passengers to the favourite number of seven hundred, in addition to Buddha himself in an earlier incarnation.

[29] So also the ship in which Buddha in the Supparaka-Bodhisat incarnation made his voyages from Bharukaccha (Broach) to "the Sea of the Seven Gems"

[30] carried seven hundred merchants besides himself. The wrecked ship of the

Vālahassa-Jātaka carried five hundred merchants.

[31] The ship which is mentioned in the

Samudda-Vanija-Jātaka was so large as to accommodate also a whole village of absconding carpenters numbering a thousand who failed to deliver the goods (furniture, etc.) for which they had been paid in advance.

[32] The ship in which the Punna brothers, merchants of Supparaka, sailed to the region of the red-sanders was so big that besides accommodating three hundred merchants, there was room left for the large cargo of that timber which they carried home.

[33] The two Burmese merchant-brothers Tapoosa and Palekat crossed the Bay of Bengal in a ship that conveyed full five hundred cartloads of their own goods, besides whatever other cargo there may have been in it.

[34] The ship in which was rescued from a watery grave the philanthropic Brahman of the

Sāṅkha-Jātaka was 800 cubics in length, 600 cubits in width, and 20 fathoms in depth, and had three masts. The ship in which the prince of the

Mahājanaka-Jātaka sailed with other traders from Chāmpā (modern Bhagalpur) for Suvarṇabhūmi (probably either Burma or the Golden Chersonese, or the whole Farther-Indian coast) had on board seven caravans with their beasts. Lastly, the

Dāthā dhātu wanso, in relating the story of the conveyance of the Tooth-relic from Dantapura to Ceylon, gives an interesting description of a ship. The royal pair (Dantakumaro and his wife) reached the port of Tamralipta, and found there "a vessel bound for Ceylon, firmly constructed with planks sewed together with ropes, having a well-rigged, lofty mast, with a spacious sail, and commanded by a skilful navigator, on the point of departure. Thereupon the two illustrious Brahmans (in disguise), in their anxiety to reach Sińhala, expeditiously made off to the vessel (in a canoe) and explained their wishes to the commander."

- It is not a printed book but a MS., to be found in the Calcutta Sanskrit College Library, called the Yuktikalpataru. Professor Aufrecht has noticed it in his Catalogue of Sanskrit MSS. Dr. [[Author:Rajendralal Mitra}} has the following comment on it (Notices of Sanskrit MSS., vol. i., no. {{sc|cclxxi]].): "Yuktikalpataru is a compilation by Bhoja Narapati. It treats of jewels, swords, horses, elephants, ornaments, flags, umbrellas, seats, ministers, ships, etc., and frequently quotes from an author of the name of Bhoja, meaning probably Bhoja Rājā of Dhara."

- लघु यत् कोमलं काष्ठं सुघटं ब्रह्मजाति तत्।

दृढ़ाङ्गं लघु यत् काष्ठमघटं क्षत्रजाति तत्॥

कोमलं गुरु यत् काष्ठं वैश्यजाति तदुच्यते।

दृढ़ाङ्गं गुरु यत् काष्ठं शूद्रजाति तदुच्यते॥

लक्षणद्वय योगेन द्विजातिः काष्ठ संग्रहः॥

- क्षत्रियकाष्ठैर्घटिता भोजमते सुखसम्पदं नौका।

- अन्ये लघुभिः सुदृढ़ैर्विदधति जलदुष्पदे नौकाम्।

- विभिन्नजातिद्वयकाष्ठजाता न श्रेयसे नापि सुखाय नौका।

नैषा चिरं तिष्ठति पच्यते च विभिद्यते सरिति मज्जते च॥

- न सिन्धुगाद्यार्हति लौहबन्धं तल्लोहकान्तैर्ह्रियते हि लौहम्।

विपद्यते तेन जलेषु नौका गुणेन बन्धं निजगाद भोजः॥

- सामान्यञ्च विशेषश्च नौकाया लक्षणद्वयम्।

- राजहस्तमितायामा तत्पादपरिणाहिनी।

तावदेवोन्नता नौका क्षुद्रेति गदिता बुधैः॥

अतः सार्द्धमितायामा तदर्द्धपरिणाहिनी।

त्रिभागेणोत्थिता नौका मध्यमेति प्रचक्ष्यते॥

क्षुद्राथ मध्यमा भीमा चपला पटला भया।

दीर्घा पत्रपुटाचैव गर्भरा मन्थरा तथा॥

नौकादशकमित्युक्तं राजहस्तैरनुक्रमम्।

एकैकवृद्धैः सार्द्धैश्च विजानीयाद् द्वयं द्बयम्।

उन्नतिश्च प्रवीणा च हस्तादर्द्धांशलक्षिता॥

अत्र भीमा भया चैव गर्भरा चाशुभप्रदा।

- मन्थरापरतोयास्तु तासामेवाम्बुधौ गतिः।

- दीर्घा चैवोन्नता चेति विशेषे द्विविधा भिदा।

- राजहस्तद्वयायामा अष्टांशपरिणाहिनी।

नौकेयं दीर्घिका नाम दशाङ्गेनोन्नतापि च॥

दीर्घिका तरणिर्लोला गत्वरा गामिनी तरिः।

जङ्घाला प्लाविनी चैव धारिणी वेगिनी तथा॥

राजहस्तैकैकवृद्ध्या—नौकानामानि वै दश।

उन्नतिः परिणाहश्च दशाष्टांशमितौ क्रमात्॥

- अत्र लोला गामिनी च प्लाविनी दुःखदा भवेत्।

लोलाया मानमारभ्य यावद्भवति गत्वरा।

लोलायाः फलमाधत्ते एवं सर्व्वासु निर्णयः॥

- राजहस्तद्वयमिता तावत् प्रसरणोन्नता।

इयमूर्द्ध्वाभिधा नौका क्षेमाय पृथिवीभुजाम्॥

ऊर्द्ध्वानूर्द्ध्वा स्वर्णमुखी गर्भिणी मन्थरा तथा।

राजहस्तैकैकवृद्ध्या नाम पञ्चत्रयं भवेत्॥

अत्रानूर्द्ध्वा गर्भिणी च निन्दितं नामयुग्मकम्।

मन्थरायाः परा यास्तु ताः शुभाय यथोद्भवम्॥

Opinions of Sanskrit scholars whom I have consulted differ as to the exact meaning of the passages above quoted from the MS. Yuktikalpataru. According to some the word राजा means चन्द्र = 1, and हस्त = 2, so that राजहस्त stands for the number 21. But according to others, with whom I agree, राजा = 16, for in the works on Astronomy or ज्योतिष्, 'महीभृत' or 'राजा' is often used to indicate that number. I have made the calculations given above on the basis of the second interpretation.

- धात्वादीनामतो वक्ष्ये निर्णयं तरिसंश्रयम्।

कनकं रजतं ताम्रं त्रितयं वा यथाक्रमम्॥

ब्रह्मादिभिः परिन्यस्य नौका चित्रणकर्मणि।

चतुःशृृङ्गा त्रिशृङ्गाभा द्विशृङ्गा चैकशृङ्गिणी॥

सितरक्तापीतनीलवर्णान् दद्याद् यथाक्रमम्॥

केशरी महिषो नागो द्विरदो व्याघ्र एव च।

पक्षी भेको मनुष्यश्च एतेषां वदनाष्टकम्॥

नावां मुखे परिन्यस्य आदित्यादिदशाभुवाम्॥

••••••नौकासु मणिविन्यासो विज्ञेयो नवदन्दवत्।

मुक्तास्तवकैर्युक्ता नौका स्यात् सर्व्वतो भद्रा॥

- सगृहा त्रिविधा प्रोक्ता सर्ब्बमध्याग्रमन्दिरा।

- सर्ब्बतो मन्दिरं यत्र सा ज्ञेया सर्ब्बमन्दिरा।

- राज्ञां कोशाश्वनारीणां यानमत्र प्रशस्यते।

- मध्यतो मन्दिरं यत्र सा ज्ञेया मध्यमन्दिरा।

राज्ञां विलासयात्रादि वर्षासु च प्रशस्यते।

- अग्रतो मन्दिरं यत्र सा ज्ञेया त्वग्रमन्दिरा।

- चिरप्रवासयात्रायां रणे काले घनात्यये।

- तुग्रोह भुज्युनश्विनोदमेघे रयिं न कश्चिन्ममृवां अवाहाः।

तमूहथु नौभिरात्मन्वतीभिरंतरिक्ष प्रुद्भिरपोदकाभिः॥

तिस्रः क्षपस्त्रिरहातिब्रजद्भिर्नासत्या भुज्युमूहथुः पतंगैः।

समुद्रस्य धन्वन्नार्द्रस्य पारे त्रिभी रथैः शतपद्भिः पलश्वैः॥

अनारंभणे तदवीरयेथामनास्थाने अग्रभणे समुद्रे।

यदश्विना ऊहथुर्भुज्युमस्तं शतारित्रां नावमानस्थिवांसं॥

The Rig Veda/Mandala 1/Hymn 116, śloka 3-5. (Wikisource contributor note)

- ततः प्रवासितो विद्वान् विदुरेण नरस्तदा।

पार्थानां दर्शयामास मनोमारुतगामिनीम्॥

सर्व्ववातसहां नावं यन्त्रयुक्तां पताकिनीम्।

शिवे भागीरथीतीरे नरैर्विश्रम्भिभिः कृताम्॥

Mahābhārata, आदिपर्व्व।

- नावां शतानां पञ्चानां कैवर्त्तानां शतं शतम।

सन्नद्धानां तथा यूनान्तिष्ठन्त्वित्यभ्यचोदयत्॥

Ayodhyā Kāndam.

- वङ्गानुत्खाय तरसा नेता नौसाधनोद्यतान्।

निचखान जयस्तम्भं गङ्गा स्रोतोऽन्तरेषु च॥

- Upham's Sacred Books of Ceylon, ii. 28, 168. Turnour's Mahāwańso, 46, 47.

- Turnour's Mahāwańso, 46.

Direct Evidences from Indian Sculpture, Painting, and Coins.

The conclusions pointed to by these literary evidences seem further to be supported by other kinds of evidence mainly monumental in their character. They are derived from old Indian art—from Indian sculpture and painting—and also from Indian coins. These evidences, though meagre in comparison with the available literary evidences, native and foreign alike, have, however, a compensating directness and freshness, nay, the permanence which Art confers, creating things of beauty that remain a joy for ever. Indeed, the light that is thrown on ancient Indian shipping by old Indian art is not yet extinguished, thanks to the durable character of old Indian monuments, thanks also to the labours of the Archaeological Department for their preservation and maintenance.

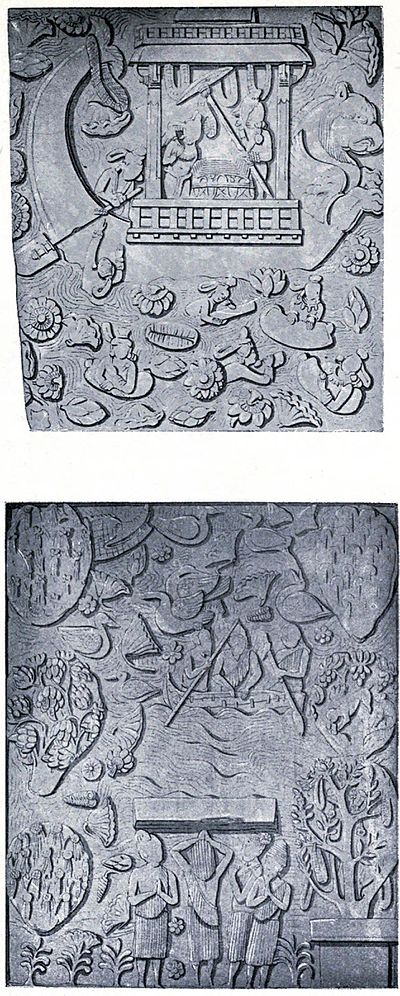

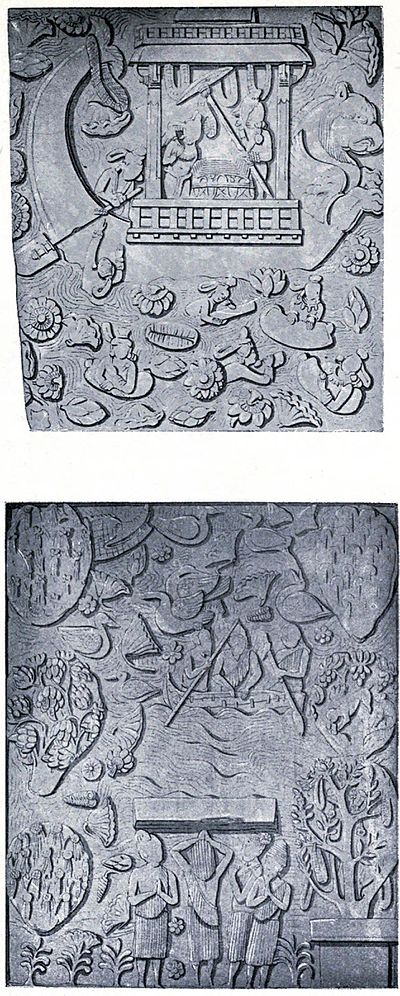

There are several representations of ships and boats in old Indian art. The earliest of them are those to be found among the Sanchi sculptures belonging to an age so far back as the 2nd century B.C. One of the sculptures on the Eastern Gateway of No. 1 Stupa at Sanchi represents a canoe made up of rough planks rudely sewn together by hemp

SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCHI STUPAS.

[

To face p. 32.

or string. "It represents a river or a sheet of fresh water with a canoe crossing it, and carrying three men in the ascetic priestly costume, two propelling and steering the boat, and the central figure, with hands resting on the gunwale, facing towards four ascetics, who are standing in reverential attitude at the water's edge below."

[1] According to Sir

A. Cunningham,

[2] the figures in the boat represent Sakya Buddha and his two principal followers; and Buddha himself has been compared in many Buddhist writings to "a boat and oar in the vast ocean of life and death."

[3] But General

F. C. Maisley is inclined to view this sculpture "as representing merely the departure on some expedition or mission of an ascetic, or priest, of rank amid the reverential farewells of his followers."

[4] His main reasons for supporting this view are, firstly, that no representations of Buddha in human shape were resorted to until several centuries later than the date of these sculptures; and, secondly, because the representation is that of a common thong-bound canoe and not of a sacred barge suiting the great Buddha. There is another sculpture to be found on the Western Gateway of No. 1 Stupa at Sanchi which "represents a piece of water, with a barge floating on it whose prow is formed by a winged gryphon and stern by a fish's tail. The barge contains a pavilion overshadowing a vacant throne, over which a male attendant holds a

chatta, while another man has a

chaori; a third man is steering or propelling the vessel with a large paddle. In the water are fresh-water flowers and buds and a large shell; and there are five men floating about, holding on by spars and inflated skins, while a sixth appears to be asking the occupant of the stern of the vessel for help out of the water."

[5] This sculpture appears simply to represent the royal state barge, which quite anticipates its modern successors used by Indian nobles at the present day, and the scene is that of the king and some of his courtiers disporting themselves in an artificial piece of water; but it is also capable of a symbolical meaning, especially when we consider that the shape of the barge here shown is that of the sacred

Makara, the fish avatara or Jataka of the Buddhist, just as the Hindu scriptures make the

Matsya, or fish, the first of the avatars of Vishnu, whose latest incarnation was Buddha. According to Lieutenant Massey, however, this sculpture represents the conveyance of relics from India to Ceylon which is intercepted by Nagas.

[6]

In passing it may be noted that the grotesque and fanciful shapes given to the prow herein represented are not the invention or innovation of an ingenious sculptor trying his wit in original design; they are strictly traditional, and conform to established standards,

[7] and are therefore identical with one or other of those possible forms of the prow of a ship which have been preserved for us in the slokas of the Sanskrit work

Yuktikalpataru quoted and referred to above.

Next to Sanchi sculptures in point of time we may mention the sculptures in the caves of Kanhery in the small island of Salsette near Bombay, belonging, according to the unerring testimony of their inscriptions, to the 2nd century A.D., the time of the Andhrabhritya or Śatakarni king Vashishthiputra (A.D. 133-162) and of Gotamiputra II. (A.D. 177-196). Among these sculptures there is a representation of a scene of shipwreck on the sea and two persons helplessly praying for rescue to god Padmapani who sends two messengers for the purpose. This is perhaps the oldest representation of a sea voyage in Indian sculpture.

[8]

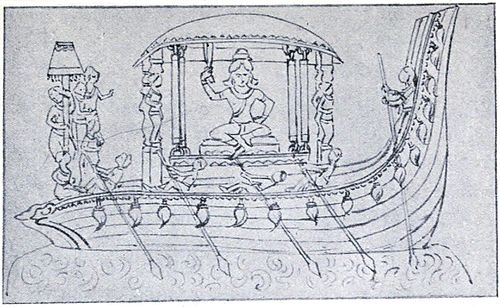

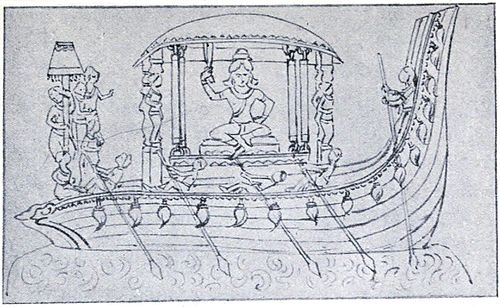

I have come across other representations of ships and boats in Indian sculpture and painting. In the course of a journey I made through Orissa and South India I noticed among the sculptures of the Temple of Jagannath at Puri a fine, well-preserved representation of a royal barge shown in relief on stone, of which I got a sketch made. The representation appears on that portion of the great Temple of Jagannath which is said to have been once a part of the Black Pagoda of Kanaraka belonging to the 12th century A.D. The sculpture shows in splendid relief a stately barge propelled by lusty oarsmen with all their might, and one almost hears the very splash of their oars; the water through which it cuts its way is thrown into ripples and waves indicated by a few simple and yet masterly touches; and the entire scene is one of dash and hurry indicative of the desperate speed of a flight or escape from danger. The beauty of the cabin and the simplicity of its design are particularly noticeable; the rocking-seat within is quite an innovation, probably meant to be effective against sea-sickness, while an equally ingenious idea is that of the rope or chain which hangs from the top and is grasped by the hand by the master of the vessel to steady himself on the rolling waters. It is difficult to ascertain what particular scene from our Shastras is here represented. It is very probably not a mere secular picture meant as an ornament. The interpretation put upon it by one of the many priests of whom I inquired, and which seems most

THE ROYAL BARGE ON THE JAGANNATH TEMPLE, PURI.

VAITAL DEUL.

[

To face p. 36.

likely, being suggested by the surrounding sculptures, was that the scene represented Śrī Krishña being secretly and hurriedly carried away beyond the destructive reach of King Kańsa. It will also be remembered that the vessel herein represented is that of the Madhyamandirā type as defined in the

Yuktikalpataru.

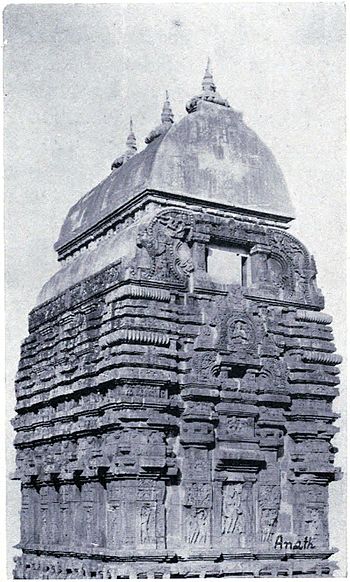

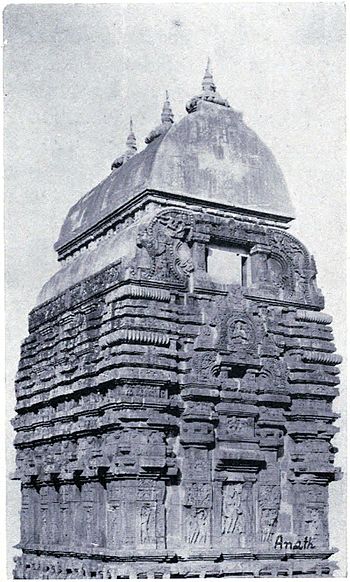

In Bhubaneshwara there is an old temple on the west side of the tank of Vindusarovara which requires to be noticed in this connection. The temple is called

Vaitāl Deul after the peculiar form of its roof resembling a ship or boat capsized, the word

vaitāra denoting a ship. The roof is more in the style of some of the Dravidian temples of Southern India, notably the

raths of Mahavellipore, than of Orissan architecture.

There are a few very fine representations of old Indian ships and boats among the far-famed paintings of the Buddhist cave-temples at Ajantā, whither the devotees of Buddhism, nineteen centuries or more ago, retreated from the distracting cares of the world to give themselves up to contemplation. There for centuries the wild ravine and the basaltic rocks were the scene of an application of labour, skill, perseverance, and endurance that went to the excavation of these painted palaces, standing to this day as monuments of a boldness of conception and a defiance of difficulty as possible, we believe, to the modern as to the ancient Indian character. The worth of the achievement will be further evident from the fact that "much of the work has been carried on with the help of artificial light, and no great stretch of imagination is necessary to picture all that this involves in the Indian climate and in situations where thorough ventilation is impossible."

[9] About the truth and precision of the work, which are no less admirable than its boldness and extent, Mr. Griffiths has the following glowing testimony:—

During my long and careful study of the caves I have not been able to detect a single instance where a mistake has been made by cutting away too much stone; for if once a slip of this kind occurred, it could only have been repaired by the insertion of a piece which would have been a blemish.

[10]

According to the best information, the execution of these works is supposed to have extended from the 2nd century B.C. to the 7th or the 8th century A.D., covering a period of more than a thousand years. The earliest caves, namely the numbers 13, 12, 10, 9, 8, arranged in the order of their age, were made under the Andhrabhrityas or Śātakarni kings in the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C., and the date of the latest ones, namely the numbers 1-5, is placed between 525-650 A.D. By the time of Hiuen Tsang's visit their execution was completed. Hiuen Tsang's is the earliest recorded reference we have to these caves. The Chinese pilgrim did not himself visit Ajantā, but he was at the capital of Pulakeshi II., King of Mahārāstra, where he heard that "on the eastern frontier of the country is a great mountain with towering crags and a continuous stretch of piled-up rocks and scarped precipice. In this there is a Sangharam (monastery) constructed in a dark valley. . . . On the four sides of the Vihara, on the stone walls, are painted different scenes in the life of the Tathagata's preparatory life as a Bodhisattva. . . . These scenes have been cut out with the greatest accuracy and finish."

[11]

The representations of ships and boats furnished by Ajantā paintings are mostly in Cave No. 2, of which the date is, as we have seen, placed between 525-650 A.D. These were the closing years of the age which witnessed the expansion of India and the spread of Indian thought and culture over the greater part of the Asiatic continent. The vitality and individuality of Indian civilization were already fully developed during the spacious times of Gupta imperialism, which about the end of the 7th century even transplanted itself to the farther East, aiding in the civilization of Java, Cambodia, Siam, China, and even Japan. After the passing away of the Gupta Empire, the government of India was in the opening of the 7th century A.D. divided between Harshavardhana of Kanauj and Pulakeshi II. of the Deccan, both of whom carried on extensive intercourse with foreign countries. The fame of Pulakeshi spread beyond the limits of India and "reached the ears of Khusru II., King of Persia, who in the thirty-sixth year of his reign, 625-6 A.D., even received a complimentary embassy from Pulakeshi. The courtesy was reciprocated by a return embassy sent from Persia, which was received in the Indian court with due honour."

[12] There is a large fresco painting in the Cave No. 1 at Ajantā which is still easily recognizable as a vivid representation of the ceremonial attending the presentation of their credentials by the Persian envoys.

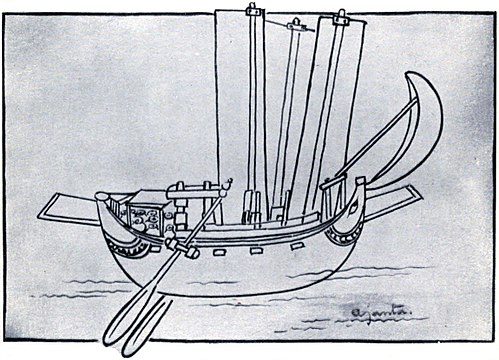

As might be naturally expected, it was also the golden age of India's maritime activity which is reflected, though dimly, in the national art of the period. The imperial fleet was thoroughly organized, consisting of hundreds of ships; and a naval invasion of Pulakeshi II. reduced Puri, "which was the mistress of the Western seas."

[13] About this time, as has been already hinted at, swarms of daring adventurers from Gujarat ports, anticipating the enterprise of the Drakes and Frobishers, or more properly of the Pilgrim Fathers,

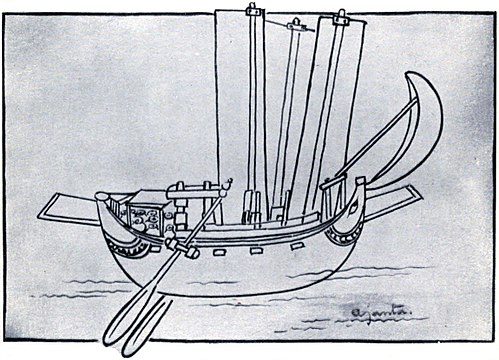

A SEA-GOING VESSEL.

(From the Ajantā Paintings.)

[

To face p. 40.

sailed in search of plenty till the shores of Java arrested their progress and gave scope to their colonizing ambition.

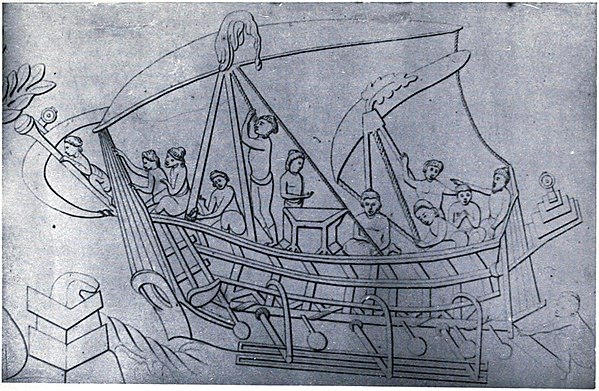

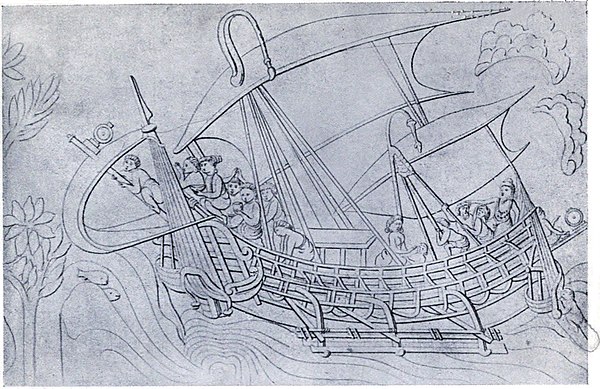

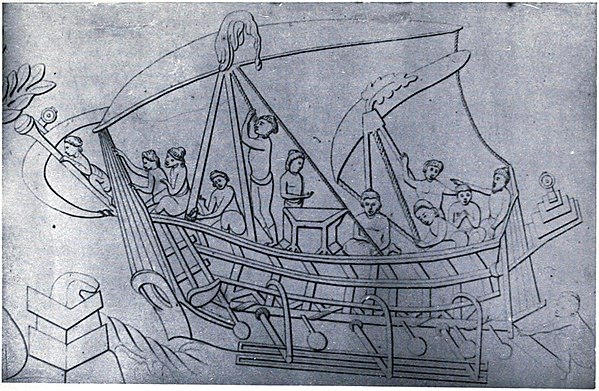

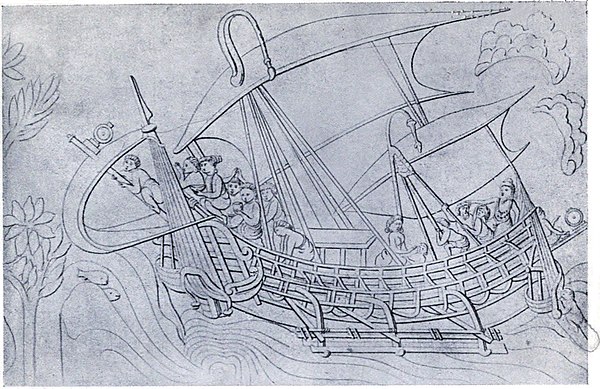

The representations of ships and boats in the Ajantā paintings are therefore rightly interpreted by Griffiths as only a "vivid testimony to the ancient foreign trade of India." Of the two representations herein reproduced, the first shows "a sea-going vessel with high stem and stern, with three oblong sails attached to as many upright masts. Each mast is surmounted by a truck, and there is carried a lug-sail. The jib is well filled with wind. A sort of bowsprit, projecting from a kind of gallows on deck, is indicated with the out-flying jib, square in form," like that borne till recent times by European vessels. The ship appears to be decked and has ports. Steering-oars hang in sockets or rowlocks on the quarter, and eyes are painted on the bows. There is also an oar behind; and under the awning are a number of jars, while two small platforms project fore and aft.

[14] The vessel is of the Agramandirā type as defined in the

Yuktikalpataru, our Sanskrit treatise on ships.

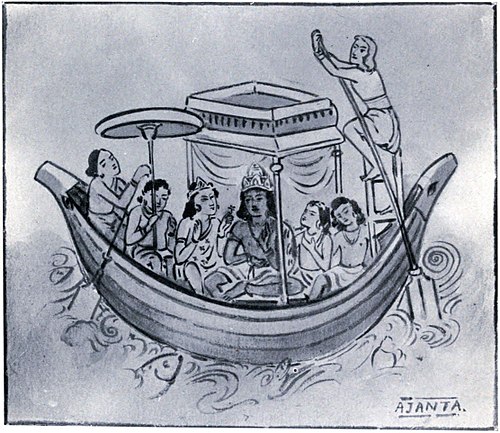

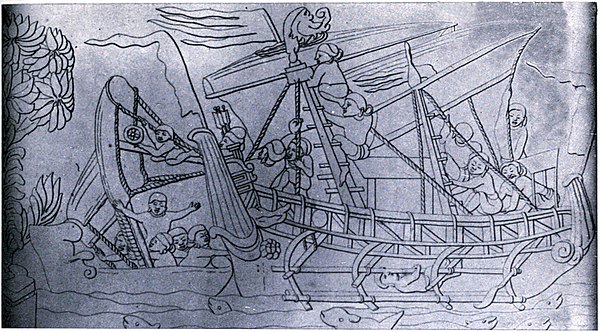

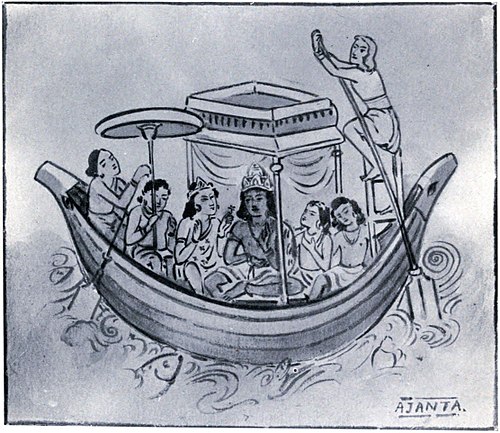

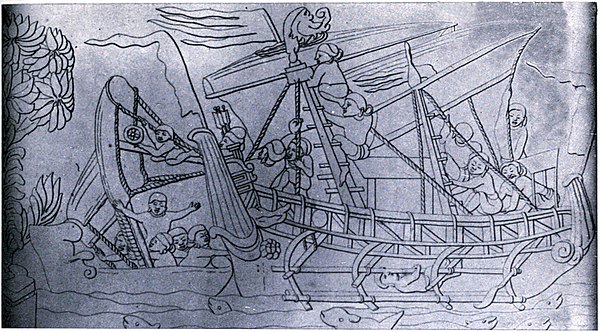

The second representation is that of the emperor's pleasure-boat, which is "like the heraldic lymphad, with painted eyes at stem and stern, a pillared canopy amidships, and an umbrella forward, the steersman being accommodated on a sort of ladder which remotely suggests the steersman's chair in the modern Burmese row-boats; while a rower is in the bows."

[15] The vessel is of the Madhyamandirā type, and corresponds exactly to the form of those vessels which, according to the

Yuktikalpataru, are to be used in pleasure trips by kings.

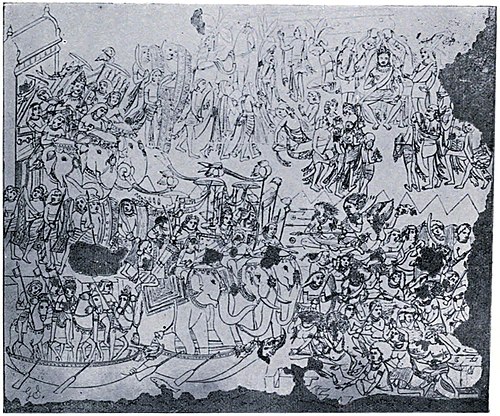

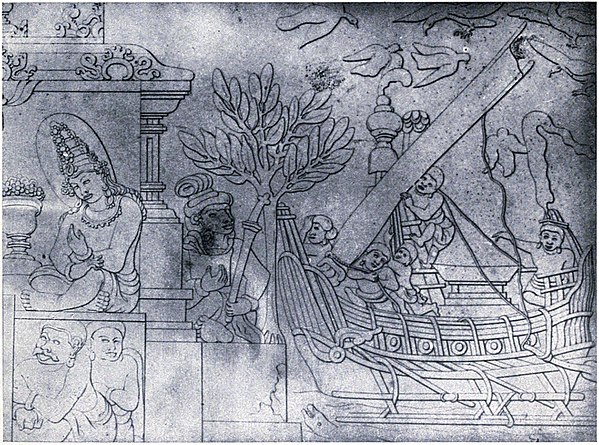

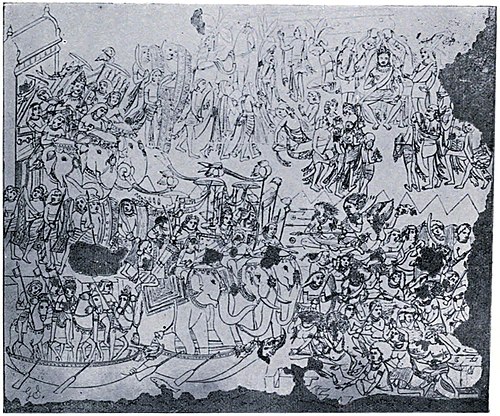

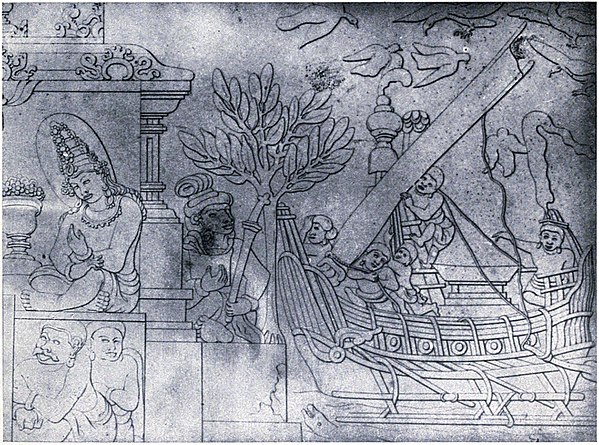

The third representation from the Ajantā paintings reproduced here is that of the scene of the landing of Vijaya in Ceylon, with his army and fleet, and his installation. The circumstances of Vijaya's banishment from Bengal with all his followers and their families are fully set forth in the Pali works,

Mahāwańso, Rājāvalliya, and the like. The fleet of Vijaya carried no less than 1,500 passengers. After touching at several places which, according to some authorities, lay on the western coast of the Deccan, the fleet reached the shores of Ceylon, approaching the island from the southern side. The date of Vijaya's landing in Ceylon is said to have been the very day on which another very important event happened in the far-off fatherland of Vijaya, for it was the day on which the Buddha attained the Nirvāṇa. Vijaya was next installed as king, and he became the founder of the "Great Dynasty."

THE ROYAL PLEASURE-BOAT.

(From the Ajantā Paintings.)

[

To face p. 42.

The conquest of Ceylon, laying as it did the foundation of a Greater India, was a national achievement that was calculated to stir deeply the popular mind, and was naturally seized by the imagination of the artist as a fit theme for the exercise of his powers. It is thus that we can explain its place in our national gallery at Ajantā as we can explain that of another similar representation suggestive of India's position in the Asiatic political system of old—I mean the representation of Pulakeshi II. receiving the Persian embassy. Truly, Ajantā unfolds some of the forgotten chapters of Indian history.

The explanation of the complex picture before us can best be given after Mr. Griffiths, than whom no one is more competent to speak on the subject. On the left of the picture, issuing from a gateway, is a chief on his great white elephant, with a bow in his hand; and two minor chiefs, likewise on elephants, each shadowed by an umbrella. They are accompanied by a retinue of foot-soldiers, some of whom bear banners and spears and others swords and shields. The drivers of the elephants, with goads in their hands, are seated, in the usual manner, on the necks of the animals. Sheaves of arrows are attached to the sides of the howdahs. The men are dressed in tightly-fitting short-sleeved jackets, and loin-cloths with long ends hanging behind in folds. Below, four soldiers on horseback with spears are in a boat, and to the right are represented again the group on their elephants, also in boats, engaged in battle, as the principal figures have just discharged their bows. The elephants sway their trunks about, as is their wont when excited. The near one is shown in the act of trumpeting, and the swing of his bell indicates motion. "These may be thought open to the criticism on Raphael's cartoon of the Draught of Fishes, viz. that his boat is too small to carry his figures. The Indian artist has used Raphael's treatment for Raphael's reason; preferring, by reduced and conventional indication of the inanimate and merely accessory vessels, to find space for expression, intelligible to his public, of the elephants and horses and their riders necessary to his story."

Vijaya Sińha, according to legend, went (B.C. 543) to Ceylon with a large following. The Rakshasis or female demons inhabiting it captivated them by their charms; but Vijaya, warned in a dream, escaped on a wonderful horse. He collected an army, gave each soldier a magic verse (

mantra), and returned. Falling upon the demons with great impetuosity, he totally routed them, some fleeing the island and others being drowned in the sea. He destroyed their town, and established himself as king in the island, to which he gave the name of Sińhala.

[16]

LANDING OF VIJAYA IN CEYLON (ABOUT 543 B.C.).

To face p. 44.

I shall now present a very important and interesting series of representations of ships which are found not in India but faraway from her, among the magnificent sculptures of the Temple of Borobudur in Java, where Indian art reached its highest expression amid the Indian environment and civilization transplanted there.

Most of the sculptures show in splendid relief ships in full sail and scenes recalling the history of the colonization of Java by Indians in the earlier centuries of the Christian era. Of one of them Mr. Havell

[17] thus speaks in appreciation: "The ship, magnificent in design and movement, is a masterpiece in itself. It tells more plainly than words the perils which the Prince of Gujarat and his companions encountered on the long and difficult voyages from the west coast of India. But these are over now. The sailors are hastening to furl the sails and bring the ship to anchor." There are other ships which appear to be sailing tempest-tossed on the ocean, fully trying the pluck and dexterity of the oarsmen, sailors, and pilots, who, however, in their movements and looks impress us with the idea that they are quite equal to the occasion. These sculptured types of a 6th or 7th century Indian ship—and it is the characteristic of Indian art to represent conventional forms or types rather than individual things—carry our mind back to the beginning of the 5th century A.D., when a similar vessel also touched the shores of Java after a more than three months' continuous sail from Ceylon with 200 passengers on board including the famous Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hien. It is noteworthy that "astern of the great ship was a smaller one as a provision in case of the larger vessel being injured or wrecked during the voyage."

[18]

The form of these ships closely resembles that of a catamaran, and somewhat answers to the following description of some Indian ships given by Nicolo Conti in the earlier part of the 15th century: "The natives of India build some ships larger than ours, capable of containing 2,000 butts, and with five sails and as many masts. The lower part is constructed with triple planks, in order to withstand the force of the tempests to which they are much exposed. But some ships are so built in compartments that should one part be shattered the other portion remaining entire may accomplish the voyage."

[19]

These ships will be found to present two types of vessels. To the first type belong Nos. 1, 3, 5, 6. They are generally longer and broader than the

INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA.

No. 1. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borobudur.)

INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA.

No. 2. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borobudur.)

[

To face p. 46.

vessels of the second type, have more than one mast, are many-ribbed, the ribs being curved, not straight. These vessels are built so narrow and top-heavy that it is necessary to fit outriggers for safety. An outrigger is a series of planks or logs joined to the boat with long poles or spars as shown in Fig. 1. It is customary when a large amount of sail is being carried for the crew to go out and stand on the outrigger as shown in Fig. 5.

No. 1 has got two masts and one long sail. No. 3 has got square sails and one stay-sail in front. In No. 5 the crew appear to be setting sail or taking sail down. No. 6 has been interpreted by Mr. Havell as representing sailors "hastening to furl the sails and bring the ship to anchor," but this suggestion seems to be contradicted by the sea-gulls or albatrosses of the sculpture flying around the vessel, which without doubt indicate that the ship is in mid-ocean, far away from land.

No. 1 shows probably a wooden figure-head and not a man; so also do Nos. 3, 5, 6. There is also a sort of cabin in each of the vessels of the first type. Again, in No. 1 the figure aft appears to be a compass.

[20] No. 5 appears to be in collision with some other vessel, or perhaps it shows a smaller vessel which used to be carried as a provision against damages or injury to the larger one from the perils of navigation. This was, as already pointed out, true of the merchantman in which Fa-Hien took passage from Ceylon to Java. No. 5 illustrates also the use of streamers to indicate the direction of winds.

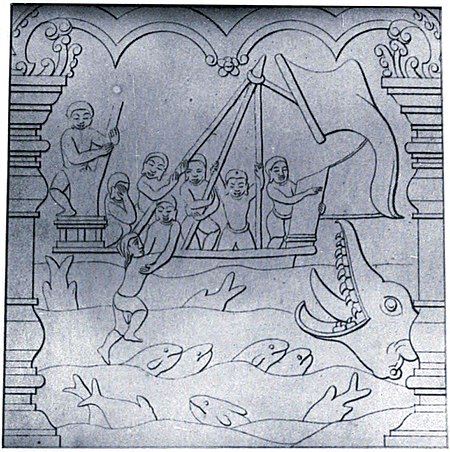

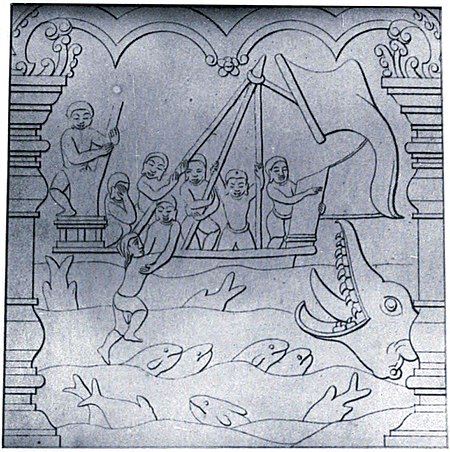

There is another type of ships represented in Nos. 2 and 4. The fronts are less curved than in the first type; there is also only one mast. No. 2 shows a scene of rescue, a drowning man being helped out of the water by his comrade. No. 4 represents a merrier scene, the party disporting themselves in catching fish.

Some of the favourite devices of Indian sculpture to indicate water may be here noticed. Fresh and sea waters are invariably and unmistakably indicated by fishes, lotuses, aquatic leaves, and the like. The

makara, or alligator, showing its fearful row of teeth in Fig. 2, is used to indicate the ocean; so also are the albatrosses or sea-gulls of Fig. 6. The curved lines are used to indicate waves.

INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA.

No. 3. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borobudur.)

INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA.

No. 4. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borobudur.)

[

To face p. 48.

INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA.

No. 5. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borobudur.)

INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA.

No. 6. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borobudur.)

[

To face p. 48.

The trees and pillars appear probably to demarcate one scene from another in the sculpture.

Finally, in the Philadelphia Museum there is a most interesting exhibit of the model of one of these Hindu-Javanese ships, an "outrigger ship," with the following notes:—

Length 60 feet. Breadth 15 feet. ...

Method of construction.—A cage-work of timber above a great log answering for a keel, the hold of the vessel being formed by planking inside the timbers; and the whole being so top-heavy as to make the outrigger essential for safety.

Reproduced from the frieze of the great Buddhist temple at Borobudur, Java, which dates probably from the 7th century A.D. About 600 A.D. there was a great migration from Guzarat in ancient India near the mouths of the Indus to the island of Java, due perhaps to the devastation of Upper India by Scythian tribes and to the drying up of the country.

[21]

Lastly, it may be mentioned that in the Great Temple at Madura, among the fresco paintings that cover the walls of the corridors round the Suvarṇapushkariṇī tank, there is a fine representation of the sea and of a ship in full sail on the main as large as those among the sculptures of Borobudur.

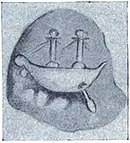

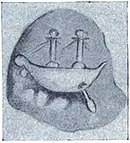

We shall now refer to the available numismatic evidence bearing on Indian shipping; for besides the representations of ships and boats in Indian sculpture and painting, there are a few interesting representations on some old Indian coins which point unmistakably to the development of Indian shipping and naval activity. Thus there has been a remarkable find of some Andhra coins on the east coast, belonging to the 2nd and 3rd century A.D., on which is to be detected the device of a two-masted ship, "evidently of large size." With regard to the meaning of the device Mr. Vincent Smith has thus remarked: "Some pieces bearing the figure of a ship suggest the inference that Yajña Śrī's (A.D. 184-213) power was not confined to the land."

[22] Again: "The ship-coins, perhaps struck by Yajña Śrī, testify to the existence of a sea-borne trade on the Coromandel coast in the 1st century of the Christian era."

[23] This inference is, of course, amply supported by what we know of the history of the Andhras, in whose times, according to R. Sewell, "there was trade both by sea and overland with Western Asia, Greece, Rome, and Egypt, as well as China and the East."

[24]

In his

South Indian Buddhist Antiquities,

[25] Alexander Rea gives illustrations and descriptions of three of these ship-coins of the Andhras. They

No. 1. | |

No. 2. |

No. 3. | |

No. 4. |

ANDHRA SHIP-COINS OF THE SECOND CENTURY A.D.

[

To face p. 51.

are all of lead, weighing respectively 101 grains, 65 grains, and 29 grains. The obverse of the first shows a ship resembling the Indian

dhoni, with bow to the right. The vessel is pointed in vertical section at each end. On the point of the stem is a round ball. The rudder, in the shape of a post with spoon on end, projects below. The deck is straight, and on it are two round objects from which rise two masts, each with a cross-tree at the top. Traces of rigging can be faintly seen. The obverse of the second shows a ship to the right. The device resembles that of the first, but the features are not quite distinct. The deck in the specimen is curved. The obverse of the third represents a device similar to the preceding, showing even more distinctly than the first. The rigging is crossed between the masts. On the right of the vessel appear three balls, and under the side are two spoon-shaped oars. No. 45 in the plate of Sir Walter Elliot's

Coins of Southern India is also a coin of lead with a two-masted ship on the obverse.

Besides these Andhra coins there have been discovered some Kurumbar or Pallava coins on the Coromandel coast, on the reverse of which there is a figure of a "two-masted ship like the modern coasting vessel or

d'honi, steered by means of oars from the stern." The Kurumbars were a pastoral tribe living in associated communities and inhabiting for some hundred years before the 7th century "the country from the base of the tableland to the Palar and Pennar Rivers. . . . They are stated to have been engaged in trade, and to have owned ships and carried on a considerable commerce by sea."

- Si-yu-ki, ii. 241.

- Turnour's Mahāwańso, 51.

- Bishop Bigandet's Life of Godama, 415.

- Hardy's Manual of Buddhism, 13.

- "Now it happened that five hundred shipwrecked traders were cast ashore near the city of these sea-goblins."

- "There stood near Benares a great town of carpenters containing a thousand families." (Cambridge translation of Jātakas.)

- Hardy, Manual of Buddhism, 57, 260.

- Bishop Bigandet's Life of Godama, 101.