UAVs and UCAVs

- Thread starter LETHALFORCE

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?plugwater

New Member

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2009

- Messages

- 4,154

- Likes

- 1,082

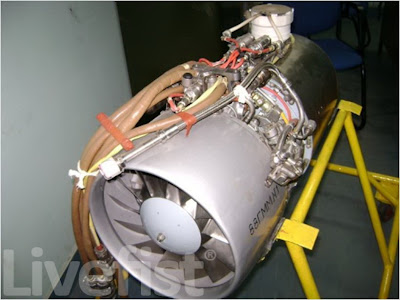

India's Mini Gas Turbine Engine For UAV/UCAV Programme

India's indigenous minaturised gas turbine technology demonstrator for UAVs/UCAVs. The Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) has completed preliminary design, configuration and analysis of the engine, under development ostensibly to power AURA, India's stealth UCAV concept.

http://www.livefist.blogspot.com/

India's indigenous minaturised gas turbine technology demonstrator for UAVs/UCAVs. The Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) has completed preliminary design, configuration and analysis of the engine, under development ostensibly to power AURA, India's stealth UCAV concept.

http://www.livefist.blogspot.com/

Rahul Singh

New Member

- Joined

- Mar 30, 2009

- Messages

- 3,652

- Likes

- 5,790

Great work Eagleone....

Patriot

New Member

- Joined

- Apr 11, 2010

- Messages

- 1,761

- Likes

- 544

UAV Market Exceeds Five Billion Dollars In 2010

by Staff Writers

London, UK (SPX) Jun 28, 2010

New market research

calculates that in 2010 the global market for unmanned aerial vehicles will reach more than $5.5bn. This can be attributed to the wide and growing popularity of UAVs as a key asset for armed forces worldwide.

Led by the US, which dominates spending on UAVs, many of the world's armed services are acquiring or developing a wide range of UAVs for use in current conflicts as well as in future scenarios. There will be steady demand across the wide range of the different types of UAVs, namely:

+ Mini UAVs

+ Tactical UAVs

+ Endurance UAVs

+ Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs)

+ Civil UAVs

The UAV market is being driven by major acquisition programmes mainly by the US but also by similar programmes in Europe and the Asia-Pacific.

The US will remain the largest market in the next few years, as it continues to acquire different UAVs for all its armed services and for use within different levels of its military units.

The use of UAVs in US border security is also on the rise. The US is also developing new types of UAVs that would provide new capabilities for future conflicts.

Several countries are following the US lead and are likewise investing in UAVs as a key force multiplier. European countries are both embarking on their own acquisition programmes or working on collaborative projects.

Israel has acquired its share of UAVs and has become a key supplier to other countries. Asian powers such as China and India, along with Japan and South Korea, which both have mature industrial and technological base, are systematically working to build up considerable UAV fleets.

The Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) Market 2010-2020: Technologies for ISR and Counter-Insurgency report reveals that several key markets are undertaking significant UAV programmes and that this will only continue in the future. This points to a steady market for UAVs over the next decade that companies currently involved in the sector, and those looking to take part in it, have the opportunity to exploit.

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/UAV_Market_Exceeds_Five_Billion_Dollars_In_2010_999.html

by Staff Writers

London, UK (SPX) Jun 28, 2010

New market research

calculates that in 2010 the global market for unmanned aerial vehicles will reach more than $5.5bn. This can be attributed to the wide and growing popularity of UAVs as a key asset for armed forces worldwide.

Led by the US, which dominates spending on UAVs, many of the world's armed services are acquiring or developing a wide range of UAVs for use in current conflicts as well as in future scenarios. There will be steady demand across the wide range of the different types of UAVs, namely:

+ Mini UAVs

+ Tactical UAVs

+ Endurance UAVs

+ Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs)

+ Civil UAVs

The UAV market is being driven by major acquisition programmes mainly by the US but also by similar programmes in Europe and the Asia-Pacific.

The US will remain the largest market in the next few years, as it continues to acquire different UAVs for all its armed services and for use within different levels of its military units.

The use of UAVs in US border security is also on the rise. The US is also developing new types of UAVs that would provide new capabilities for future conflicts.

Several countries are following the US lead and are likewise investing in UAVs as a key force multiplier. European countries are both embarking on their own acquisition programmes or working on collaborative projects.

Israel has acquired its share of UAVs and has become a key supplier to other countries. Asian powers such as China and India, along with Japan and South Korea, which both have mature industrial and technological base, are systematically working to build up considerable UAV fleets.

The Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) Market 2010-2020: Technologies for ISR and Counter-Insurgency report reveals that several key markets are undertaking significant UAV programmes and that this will only continue in the future. This points to a steady market for UAVs over the next decade that companies currently involved in the sector, and those looking to take part in it, have the opportunity to exploit.

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/UAV_Market_Exceeds_Five_Billion_Dollars_In_2010_999.html

Patriot

New Member

- Joined

- Apr 11, 2010

- Messages

- 1,761

- Likes

- 544

Fighting a real war in a virtual cockpit

6/28/2010

As his wife got dressed on a recent weekday morning, Jon Stiles settled the couple's 1-year-old daughter into a highchair with an Eggo waffle and soy sausage.

Lately Stiles had been working a swing shift, so he had time to read his daughter a few Sesame Street books, walk June Bug, the family's dachshund-beagle mix, and hit a cycling class at the gym before starting his 45-minute commute.

"Then it's kiss the baby, kiss the wife goodbye, pet the dog and out the door," Stiles said.

His pre-work ritual is pretty typical of any suburban Houston dad.

His job is anything but.

Inside a windowless room at Houston's Ellington Airport, the 36-year-old major with the Texas Air National Guard will sit down at the controls of a Predator drone as it cruises over insurgent hideouts and convoy routes in Afghanistan or Iraq.

Although it's late afternoon in Houston, the sun is about to rise in the combat zone.

Via satellite, Stiles will talk to ground troops on the front lines who depend on the high-resolution, real-time images collected by his Predator's sensors. He will look for evidence of bombs planted in or alongside roadways, or suspicious people carrying weapons on rugged mountain trails.

"You might be doing a convoy escort, guys moving 20 to 30 vehicles from point A to point B, and you're just scanning ahead of them, trying to make sure no one is going to ambush them," Stiles said. "It kinda gives 'em a warm, fuzzy feeling to know there's somebody up there looking after them."

Integral part of the war

This long-distance warfare might sound like science fiction, but for Stiles, it's all too real.

"Sometimes I'll hear guys screaming and gunfire in the background," he said. "Your heart's racing, probably just like theirs, even though you're not actually there."

Many Houstonians who drive past Ellington Airport on Old Galveston Road probably assume the Air Guard Station is closed, the victim of budget cuts and consolidation.

In fact, Ellington's Air Guard plays an even more integral part in the war effort now than it did two years ago, when the 147th Reconnaissance Wing lost its fleet of F-16s.

A base realignment sent the wing's 15 fighter jets to a boneyard in 2008. The F-16 mechanics, pilots and support staff were given a choice: They could retrain on Predators, or move on.

Stiles, a fighter pilot with two Iraq tours under his belt, chose to stay. Now he and other members of the 147th are flying Predators in Afghanistan and Iraq, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

"From having nearly disappeared entirely — this base and this wing — we're in a great position," said the 147th's commander, Col. Ken Wisian.

"We're in what is the largest growth industry in the military. We have a secure future. We're doing leading-edge work. We're in the fight, day-to-day."

The wing's transition from F-16s to unmanned aircraft here in Houston reflects a larger trend that's transforming the Air Force and Air Guard as the U.S. military comes to rely on drones for surveillance and targeting of enemy forces.

Nowhere to go but up

Since 2006, the Pentagon's unmanned aircraft operations increased from about 165,000 hours to more than 550,000 now, with the annual budget allotment for such systems growing from $1.7 billion in 2006 to $4.2 billion in 2010.

At the same time, the military's inventory of drones has gone from fewer than 3,000 to more than 6,500, a number that Department of Defense officials expect to grow significantly over the next five years.

"The demand for this kind of capacity is insatiable," said Wisian. "As fast as we produce crews and equipment, they're in the fight."

He doesn't think drones will replace manned aircraft completely, but he's convinced that they're the future of air power.

"We're still just figuring out this way of warfare, and it's revolutionary," he said.

For Staff Sgt. Nicolas Gassiott, who served as an F-16 crew chief, the transition from fighter jets to drones didn't come easy.

"In the beginning you go from basically being a race car driver to being a Pinto mechanic," Gassiott said. "It's a hard pill to swallow."

Retrained and refocused

An F-16 typically needs five or six people to change an engine, for example, but three would be too many for a Predator, which is powered by what Wisian describes as a "souped-up snowmobile engine."

Gassiott believes the Predator's simple design is part of its genius.

He can lift the nose of the aircraft with one hand. It needs a fraction of the fuel required by an F-16 and is a fraction of the cost. It can beam detailed, real-time images of the battlefield halfway around the world. And it can stay aloft for more the 20 hours, fully armed.

"Basically we took like two steps back, and we took 5,000 leaps forward," said Gassiott. "It's a new frontier. It's not just the newest war machine; it's changing all of aviation history."

At Ellington, the hundreds of workers needed to maintain a fleet of F-16s have been reduced to a handful.

Some of the wing's former flight-line personnel went through retraining and now serve on Predator crews as sensor operators or mission intelligence coordinators.

These days, Gassiott rattles around Ellington Airport's near-empty hangers, patching up Predators used for demonstrations and training. He's worked overseas, too, as part of a team that launches the drones before the pilots at ground control stations in the U.S. take over.

Showing off one of the wing's Predators on a rainy day, Gassiott patted the grey carbon-fiber frame affectionately.

His colleagues had painted it according to tradition with a pilot's call sign and crew chief's name, in addition to the words "Houston" and "Texas Air Guard."

The Predator might not be a glamorous aircraft, but it gets the job done, Gassiott said.

"This is the airframe most feared by insurgents, al-Qaida and the Taliban," he said. "At 20,000 feet we can put a Hellfire (missile) through a standard windowpane."

Three-member crews

At any given time, the ground control station inside a top-security building at Ellington has two Predators in the skies over Afghanistan or Iraq. Each drone is controlled by a three-member crew. Crews rotate in shifts, so they're always fresh.

"I think of it as an airborne scout and an airborne sniper," Wisian said. "We can stay over a spot and watch for nearly a day, and that changes what you have available for the ground commanders. You can wait. You can be patient."

During Iraqi national elections in March, for example, Predators flown by crews at Ellington circled over polling sites for hours to protect voters and Iraqi security forces, Wisian said.

Other times, Ellington crews watching roads in Iraq or Afghanistan have caught insurgents planting improvised explosive devices. Crews also have been involved in major firefights in Afghanistan over the past year, Wisian said. During those battles, they provided a live picture of the situation for troops on the ground, coordinated close air support by "talking" incoming fighter jets onto their targets, and delivered precision strikes using the Predator's Hellfire missiles.

Missions don't always go smoothly.

In May, a military investigation blamed "inaccurate and unprofessional" reporting by Predator operators at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada for a missile strike that killed 23 Afghan civilians. The incident demonstrated the risks of drone warfare.

'It's the real thing'

Wisian said there are multiple people who must sign off before a Predator opens fire, and they tend to err on the side of caution. He's seen crews wave off a target because they feared hitting bystanders.

"There's very strong procedures that are followed to avoid just that kind of thing," he said. "There's no doubt we are doing the best job in history of minimizing civilian casualties. This is a 'hearts and minds' war."

Predator crew members say they understand the gravity of their work situation.

"It's definitely not a video game," said Maj. Robert Farmer, a pilot. "It's the real thing. And the things that we do are keeping Americans safe and playing a large role in the global war on terror, so I take it seriously."

It can be hard not to let the stress of the job follow you home.

"Before, when you deployed, you really had to think about it every 18 months," Stiles said. "Now we're always in combat."

Mission takes priority

Stiles uses his commute to get in the right head space. On the drive to work, he tunes his radio to R&B and reviews mission scenarios.

"I just try to flip the switch," he said. "Like today, my child is sick. I can't dwell on that because I might miss something during the mission."

Family members know that when Predator crews are on duty, they can't take phone calls to remind them to pick up the kids or grab a carton of milk.

"When I was in a F-16, there was no way my wife would call me," Stiles said. "So we try to keep that same mindset."

One phone call did get through to Stiles, however. In May of last year, his wife called. She was in labor with their first child. Another pilot took over so Stiles could go to the hospital.

"I flew a combat mission overseas and saw my daughter born, all within a couple of hours," Stiles said. "So that was pretty neat."

http://news.combataircraft.com/readnews.aspx?i=1406

6/28/2010

As his wife got dressed on a recent weekday morning, Jon Stiles settled the couple's 1-year-old daughter into a highchair with an Eggo waffle and soy sausage.

Lately Stiles had been working a swing shift, so he had time to read his daughter a few Sesame Street books, walk June Bug, the family's dachshund-beagle mix, and hit a cycling class at the gym before starting his 45-minute commute.

"Then it's kiss the baby, kiss the wife goodbye, pet the dog and out the door," Stiles said.

His pre-work ritual is pretty typical of any suburban Houston dad.

His job is anything but.

Inside a windowless room at Houston's Ellington Airport, the 36-year-old major with the Texas Air National Guard will sit down at the controls of a Predator drone as it cruises over insurgent hideouts and convoy routes in Afghanistan or Iraq.

Although it's late afternoon in Houston, the sun is about to rise in the combat zone.

Via satellite, Stiles will talk to ground troops on the front lines who depend on the high-resolution, real-time images collected by his Predator's sensors. He will look for evidence of bombs planted in or alongside roadways, or suspicious people carrying weapons on rugged mountain trails.

"You might be doing a convoy escort, guys moving 20 to 30 vehicles from point A to point B, and you're just scanning ahead of them, trying to make sure no one is going to ambush them," Stiles said. "It kinda gives 'em a warm, fuzzy feeling to know there's somebody up there looking after them."

Integral part of the war

This long-distance warfare might sound like science fiction, but for Stiles, it's all too real.

"Sometimes I'll hear guys screaming and gunfire in the background," he said. "Your heart's racing, probably just like theirs, even though you're not actually there."

Many Houstonians who drive past Ellington Airport on Old Galveston Road probably assume the Air Guard Station is closed, the victim of budget cuts and consolidation.

In fact, Ellington's Air Guard plays an even more integral part in the war effort now than it did two years ago, when the 147th Reconnaissance Wing lost its fleet of F-16s.

A base realignment sent the wing's 15 fighter jets to a boneyard in 2008. The F-16 mechanics, pilots and support staff were given a choice: They could retrain on Predators, or move on.

Stiles, a fighter pilot with two Iraq tours under his belt, chose to stay. Now he and other members of the 147th are flying Predators in Afghanistan and Iraq, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

"From having nearly disappeared entirely — this base and this wing — we're in a great position," said the 147th's commander, Col. Ken Wisian.

"We're in what is the largest growth industry in the military. We have a secure future. We're doing leading-edge work. We're in the fight, day-to-day."

The wing's transition from F-16s to unmanned aircraft here in Houston reflects a larger trend that's transforming the Air Force and Air Guard as the U.S. military comes to rely on drones for surveillance and targeting of enemy forces.

Nowhere to go but up

Since 2006, the Pentagon's unmanned aircraft operations increased from about 165,000 hours to more than 550,000 now, with the annual budget allotment for such systems growing from $1.7 billion in 2006 to $4.2 billion in 2010.

At the same time, the military's inventory of drones has gone from fewer than 3,000 to more than 6,500, a number that Department of Defense officials expect to grow significantly over the next five years.

"The demand for this kind of capacity is insatiable," said Wisian. "As fast as we produce crews and equipment, they're in the fight."

He doesn't think drones will replace manned aircraft completely, but he's convinced that they're the future of air power.

"We're still just figuring out this way of warfare, and it's revolutionary," he said.

For Staff Sgt. Nicolas Gassiott, who served as an F-16 crew chief, the transition from fighter jets to drones didn't come easy.

"In the beginning you go from basically being a race car driver to being a Pinto mechanic," Gassiott said. "It's a hard pill to swallow."

Retrained and refocused

An F-16 typically needs five or six people to change an engine, for example, but three would be too many for a Predator, which is powered by what Wisian describes as a "souped-up snowmobile engine."

Gassiott believes the Predator's simple design is part of its genius.

He can lift the nose of the aircraft with one hand. It needs a fraction of the fuel required by an F-16 and is a fraction of the cost. It can beam detailed, real-time images of the battlefield halfway around the world. And it can stay aloft for more the 20 hours, fully armed.

"Basically we took like two steps back, and we took 5,000 leaps forward," said Gassiott. "It's a new frontier. It's not just the newest war machine; it's changing all of aviation history."

At Ellington, the hundreds of workers needed to maintain a fleet of F-16s have been reduced to a handful.

Some of the wing's former flight-line personnel went through retraining and now serve on Predator crews as sensor operators or mission intelligence coordinators.

These days, Gassiott rattles around Ellington Airport's near-empty hangers, patching up Predators used for demonstrations and training. He's worked overseas, too, as part of a team that launches the drones before the pilots at ground control stations in the U.S. take over.

Showing off one of the wing's Predators on a rainy day, Gassiott patted the grey carbon-fiber frame affectionately.

His colleagues had painted it according to tradition with a pilot's call sign and crew chief's name, in addition to the words "Houston" and "Texas Air Guard."

The Predator might not be a glamorous aircraft, but it gets the job done, Gassiott said.

"This is the airframe most feared by insurgents, al-Qaida and the Taliban," he said. "At 20,000 feet we can put a Hellfire (missile) through a standard windowpane."

Three-member crews

At any given time, the ground control station inside a top-security building at Ellington has two Predators in the skies over Afghanistan or Iraq. Each drone is controlled by a three-member crew. Crews rotate in shifts, so they're always fresh.

"I think of it as an airborne scout and an airborne sniper," Wisian said. "We can stay over a spot and watch for nearly a day, and that changes what you have available for the ground commanders. You can wait. You can be patient."

During Iraqi national elections in March, for example, Predators flown by crews at Ellington circled over polling sites for hours to protect voters and Iraqi security forces, Wisian said.

Other times, Ellington crews watching roads in Iraq or Afghanistan have caught insurgents planting improvised explosive devices. Crews also have been involved in major firefights in Afghanistan over the past year, Wisian said. During those battles, they provided a live picture of the situation for troops on the ground, coordinated close air support by "talking" incoming fighter jets onto their targets, and delivered precision strikes using the Predator's Hellfire missiles.

Missions don't always go smoothly.

In May, a military investigation blamed "inaccurate and unprofessional" reporting by Predator operators at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada for a missile strike that killed 23 Afghan civilians. The incident demonstrated the risks of drone warfare.

'It's the real thing'

Wisian said there are multiple people who must sign off before a Predator opens fire, and they tend to err on the side of caution. He's seen crews wave off a target because they feared hitting bystanders.

"There's very strong procedures that are followed to avoid just that kind of thing," he said. "There's no doubt we are doing the best job in history of minimizing civilian casualties. This is a 'hearts and minds' war."

Predator crew members say they understand the gravity of their work situation.

"It's definitely not a video game," said Maj. Robert Farmer, a pilot. "It's the real thing. And the things that we do are keeping Americans safe and playing a large role in the global war on terror, so I take it seriously."

It can be hard not to let the stress of the job follow you home.

"Before, when you deployed, you really had to think about it every 18 months," Stiles said. "Now we're always in combat."

Mission takes priority

Stiles uses his commute to get in the right head space. On the drive to work, he tunes his radio to R&B and reviews mission scenarios.

"I just try to flip the switch," he said. "Like today, my child is sick. I can't dwell on that because I might miss something during the mission."

Family members know that when Predator crews are on duty, they can't take phone calls to remind them to pick up the kids or grab a carton of milk.

"When I was in a F-16, there was no way my wife would call me," Stiles said. "So we try to keep that same mindset."

One phone call did get through to Stiles, however. In May of last year, his wife called. She was in labor with their first child. Another pilot took over so Stiles could go to the hospital.

"I flew a combat mission overseas and saw my daughter born, all within a couple of hours," Stiles said. "So that was pretty neat."

http://news.combataircraft.com/readnews.aspx?i=1406

Patriot

New Member

- Joined

- Apr 11, 2010

- Messages

- 1,761

- Likes

- 544

Global Hawk at risk of being "non-affordable", DOD says

By Stephen Trimble

The US military's top weapons buyer today repeated cost concerns about the Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk first raised by a senior air force official 10 days ago.

The high-altitude unmanned aircraft system (UAS) is "on a path to be non-affordable", undersecretary of acquisition technology and logistics Ashton Carter told reporters.

Carter's comment on Global Hawk came as he announced a DOD initiative to generate 2-3% savings annually by slashing costs in the DOD's $400 billion budget spent on contractors.

The streamlining cuts across all programmes, but Global Hawk will be among the first subjected to a "should-cost" review by the DOD's cost analysts, Carter says. The review is intended to produce an independent view on what the DOD should actually be paying, versus what the contractor charges.

Concerns about the Global Hawk's cost have grown as Northrop's price rises despite heavier demand for the product, Carter says. By contrast, in the private sector, higher demand for computers produces cheaper and better products every year, he adds.

Similarly, demand for the Global Hawk has grown steadily since the long-endurance aircraft was introduced in the mid-1990s.

At least six versions of the Global Hawk, including four by the air force and two by the navy, have been or are being purchased by DOD. Northrop also has sold an export version of the aircraft to Germany called EuroHawk.

"All have a roughly comparable airframe," Carter says. "Why are these things costing more every year and not less?"

On 18 June, air force assistant secretary for acquisition David Van Buren told reporters he is "not happy with the cost of the air vehicle" and that testing has been slower than expected.

Northrop countered the air force's critical comments last week, saying overall costs have declined and not increased. Northrop attributes "cost spikes" to quantities purchased in individual lots.

Meanwhile, air force and navy leaders have been working to increase the commonality between the Global Hawk fleet and the Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) programme. The focus has been on sharing systems and components in the ground systems for both fleets, as well as production efficiency.

http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2010/06/28/343795/global-hawk-at-risk-of-being-non-affordable-dod-says.html

By Stephen Trimble

The US military's top weapons buyer today repeated cost concerns about the Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk first raised by a senior air force official 10 days ago.

The high-altitude unmanned aircraft system (UAS) is "on a path to be non-affordable", undersecretary of acquisition technology and logistics Ashton Carter told reporters.

Carter's comment on Global Hawk came as he announced a DOD initiative to generate 2-3% savings annually by slashing costs in the DOD's $400 billion budget spent on contractors.

The streamlining cuts across all programmes, but Global Hawk will be among the first subjected to a "should-cost" review by the DOD's cost analysts, Carter says. The review is intended to produce an independent view on what the DOD should actually be paying, versus what the contractor charges.

Concerns about the Global Hawk's cost have grown as Northrop's price rises despite heavier demand for the product, Carter says. By contrast, in the private sector, higher demand for computers produces cheaper and better products every year, he adds.

Similarly, demand for the Global Hawk has grown steadily since the long-endurance aircraft was introduced in the mid-1990s.

At least six versions of the Global Hawk, including four by the air force and two by the navy, have been or are being purchased by DOD. Northrop also has sold an export version of the aircraft to Germany called EuroHawk.

"All have a roughly comparable airframe," Carter says. "Why are these things costing more every year and not less?"

On 18 June, air force assistant secretary for acquisition David Van Buren told reporters he is "not happy with the cost of the air vehicle" and that testing has been slower than expected.

Northrop countered the air force's critical comments last week, saying overall costs have declined and not increased. Northrop attributes "cost spikes" to quantities purchased in individual lots.

Meanwhile, air force and navy leaders have been working to increase the commonality between the Global Hawk fleet and the Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) programme. The focus has been on sharing systems and components in the ground systems for both fleets, as well as production efficiency.

http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2010/06/28/343795/global-hawk-at-risk-of-being-non-affordable-dod-says.html

LETHALFORCE

New Member

- Joined

- Feb 16, 2009

- Messages

- 29,968

- Likes

- 48,929

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Spy_in_the_sky_rakes_in_millions_for_Israel_999.html

Spy in the sky rakes in millions for Israel

The eyes in the sky of modern warfare, whose hallmark hum is heard over Afghanistan, Iraq and Gaza, drones are a key weapon and a major cash earner for Israel, the world's largest exporter of pilotless planes.

With more than 1,000 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) sold, Israel has raked in several hundred million dollars over the years.

Israel's fleet ranges from aircraft which fit in a soldier's backpack to planes the size of a Boeing 737 that can fly as far as Iran.

The flying robots can be used to watch, hunt and kill.

Interest is such that a Turkish military delegation reportedly made a secret trip to Israel last month for training in remote piloting of the Heron drone, despite a major diplomatic crisis between the two countries.

"It's good for reaching remote targets, wherever it's needed," an officer who would only identify himself as Captain Gil, said, pointing to an IAI Heron on the tarmac of the Palmahim Air Base, near Tel Aviv.

The plane, known in Israel as Shoval -- "trail" in Hebrew -- has a 16-metre (52-foot) wingspan, can fly at an altitude of 30,000 feet (almost 10 kilometres) and can stay in the air for 40 hours.

It carries an array of sensors and radar systems, transmits information in real time, and is equipped with missiles.

"It can stay above a target a long time, without fear a pilot might get shot," said Gil as the bright sunlight reflected on the aircraft's silver fuselage.

The sound of a drone circling over the base could be heard. A monotonous hum that is all too well known to residents of the Gaza Strip, where at times it is followed by a deadly air strike.

UAVs played a key role in the devastating 22-day offensive against the Palestinian enclave which Israel launched on December 27, 2008 in a bid to end daily rocket fire against the Jewish state.

Drones -- US-made in this case -- are also widely used in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, both to monitor and to strike.

Turkey says it is using Israeli drones, in coordination with the Americans, for surveillance in northern Iraq, the rear base for attacks on Turkish targets by the separatist Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK.)

Israel prides itself on the cutting-edge technology of its UAVs, but human rights groups said scores of Palestinian civilians were killed by drones during the Gaza offensive.

Israel insists it does all it can to avoid civilian casualties, while Gil stressed that drones are crucial to troop protection.

Gil, who sports aviator-type sunglasses, is a pilot, but one who sits outside the plane -- behind a computer in an office set up in a container.

Take-off and landing is generally done manually, with the computer taking over, unless manually overridden, for the rest of the flight.

Israel recently unveiled the Heron TP, also known as Eitan -- Hebrew for "strong" -- a 4.5-ton flying behemoth about the size of a 737 whose autonomy puts it well within range of Iran -- the Jewish state's arch-enemy.

At the other end of the scale is a hand-sized and -launched flying machine.

"Israel is the world's leading exporter of drones, with more than 1,000 sold in 42 countries," says Jacques Chemla, head engineer at the UAV department of the state-owned Israel Aircraft Industries, the flagship of the country's defence industry,

That, he says, brings in about 350 million dollars a year.

Spy in the sky rakes in millions for Israel

The eyes in the sky of modern warfare, whose hallmark hum is heard over Afghanistan, Iraq and Gaza, drones are a key weapon and a major cash earner for Israel, the world's largest exporter of pilotless planes.

With more than 1,000 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) sold, Israel has raked in several hundred million dollars over the years.

Israel's fleet ranges from aircraft which fit in a soldier's backpack to planes the size of a Boeing 737 that can fly as far as Iran.

The flying robots can be used to watch, hunt and kill.

Interest is such that a Turkish military delegation reportedly made a secret trip to Israel last month for training in remote piloting of the Heron drone, despite a major diplomatic crisis between the two countries.

"It's good for reaching remote targets, wherever it's needed," an officer who would only identify himself as Captain Gil, said, pointing to an IAI Heron on the tarmac of the Palmahim Air Base, near Tel Aviv.

The plane, known in Israel as Shoval -- "trail" in Hebrew -- has a 16-metre (52-foot) wingspan, can fly at an altitude of 30,000 feet (almost 10 kilometres) and can stay in the air for 40 hours.

It carries an array of sensors and radar systems, transmits information in real time, and is equipped with missiles.

"It can stay above a target a long time, without fear a pilot might get shot," said Gil as the bright sunlight reflected on the aircraft's silver fuselage.

The sound of a drone circling over the base could be heard. A monotonous hum that is all too well known to residents of the Gaza Strip, where at times it is followed by a deadly air strike.

UAVs played a key role in the devastating 22-day offensive against the Palestinian enclave which Israel launched on December 27, 2008 in a bid to end daily rocket fire against the Jewish state.

Drones -- US-made in this case -- are also widely used in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, both to monitor and to strike.

Turkey says it is using Israeli drones, in coordination with the Americans, for surveillance in northern Iraq, the rear base for attacks on Turkish targets by the separatist Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK.)

Israel prides itself on the cutting-edge technology of its UAVs, but human rights groups said scores of Palestinian civilians were killed by drones during the Gaza offensive.

Israel insists it does all it can to avoid civilian casualties, while Gil stressed that drones are crucial to troop protection.

Gil, who sports aviator-type sunglasses, is a pilot, but one who sits outside the plane -- behind a computer in an office set up in a container.

Take-off and landing is generally done manually, with the computer taking over, unless manually overridden, for the rest of the flight.

Israel recently unveiled the Heron TP, also known as Eitan -- Hebrew for "strong" -- a 4.5-ton flying behemoth about the size of a 737 whose autonomy puts it well within range of Iran -- the Jewish state's arch-enemy.

At the other end of the scale is a hand-sized and -launched flying machine.

"Israel is the world's leading exporter of drones, with more than 1,000 sold in 42 countries," says Jacques Chemla, head engineer at the UAV department of the state-owned Israel Aircraft Industries, the flagship of the country's defence industry,

That, he says, brings in about 350 million dollars a year.

EagleOne

New Member

- Joined

- May 10, 2010

- Messages

- 886

- Likes

- 87

BAE hails Mantis UAV success, nears Taranis roll-out

BAE Systems' Mantis unmanned air vehicle technology demonstrator has been shipped back to the UK, after completing a successful first flight-test campaign in Australia.

Returned to BAE's Warton site in Lancashire in mid-June, the Mantis is in rebuild ahead of undergoing further ground-based system development work at the site. However, the company has yet to decide whether its current demonstrator will be flown again.

"Mantis was about demonstrating an end-to-end capability," says Dave Kershaw, business development and strategy director for Autonomous Systems & Future Capability, part of BAE's Military Air Systems unit. "The test flights went to show that it could go to the endurance planned."

The twin turboprop-powered aircraft made an undisclosed number of flights from the Woomera test range in South Australia, including five described as "mission-representative". Kershaw says these included tasks such as automatically tracking a ground area for targets, and cross-cueing the aircraft's two on-board payloads: an L-3 Wescam MX-20 electro-optical/infrared camera and BAE's imagery collection and exploitation system.

One night flight was also made, and BAE also assessed the time needed to prepare the UAV to take off again after completing a sortie. This demonstrated a 30min performance. The 19.8m (65ft) wingspan Mantis made its first flight from Woomera in November 2009.

BAE says a production version of Mantis would be able to fly at altitudes up to 50,000ft and deliver an endurance of over 36h. The design is a potential candidate for the UK Ministry of Defence's Scavenger requirement, which seeks a persistent intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance capability to enter use from around 2015 to 2018.

The MoD is expected to downselect its preferred option for Scavenger in 2012, with possible alternatives including the X-UAS development of EADS Defence & Security's Talarion UAV, which is already being offered to France, Germany, Spain and Turkey. However, the UK is also looking at whether its requirements could be met under a potential collaboration with the French defence ministry, Kershaw says.

Meanwhile, BAE will roll out its Taranis unmanned combat air vehicle demonstrator (artist's impression pictured below) during an event to be staged at its Warton facility on 12 July.

The Euro Hawk® unmanned reconnaissance aircraft takes off for its maiden flight June 29, 2010 from Northrop Grumman's Palmdale, Calif., manufacturing facility

BAE Systems' Mantis unmanned air vehicle technology demonstrator has been shipped back to the UK, after completing a successful first flight-test campaign in Australia.

Returned to BAE's Warton site in Lancashire in mid-June, the Mantis is in rebuild ahead of undergoing further ground-based system development work at the site. However, the company has yet to decide whether its current demonstrator will be flown again.

"Mantis was about demonstrating an end-to-end capability," says Dave Kershaw, business development and strategy director for Autonomous Systems & Future Capability, part of BAE's Military Air Systems unit. "The test flights went to show that it could go to the endurance planned."

The twin turboprop-powered aircraft made an undisclosed number of flights from the Woomera test range in South Australia, including five described as "mission-representative". Kershaw says these included tasks such as automatically tracking a ground area for targets, and cross-cueing the aircraft's two on-board payloads: an L-3 Wescam MX-20 electro-optical/infrared camera and BAE's imagery collection and exploitation system.

One night flight was also made, and BAE also assessed the time needed to prepare the UAV to take off again after completing a sortie. This demonstrated a 30min performance. The 19.8m (65ft) wingspan Mantis made its first flight from Woomera in November 2009.

BAE says a production version of Mantis would be able to fly at altitudes up to 50,000ft and deliver an endurance of over 36h. The design is a potential candidate for the UK Ministry of Defence's Scavenger requirement, which seeks a persistent intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance capability to enter use from around 2015 to 2018.

The MoD is expected to downselect its preferred option for Scavenger in 2012, with possible alternatives including the X-UAS development of EADS Defence & Security's Talarion UAV, which is already being offered to France, Germany, Spain and Turkey. However, the UK is also looking at whether its requirements could be met under a potential collaboration with the French defence ministry, Kershaw says.

Meanwhile, BAE will roll out its Taranis unmanned combat air vehicle demonstrator (artist's impression pictured below) during an event to be staged at its Warton facility on 12 July.

The Euro Hawk® unmanned reconnaissance aircraft takes off for its maiden flight June 29, 2010 from Northrop Grumman's Palmdale, Calif., manufacturing facility

Last edited:

plugwater

New Member

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2009

- Messages

- 4,154

- Likes

- 1,082

AIT software for precise UAV landing

The ARMY Institute of Technology (AIT) has developed a software programme which, it claims, increases the precision in landing of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by doing away with the need for even a human remote operator.

The institute has developed a MATLAB software programme that not only increases the precision of landing of the UAVs to 97 per cent but even makes it happen automatically without these vehicles being guided by a hand-held remote. The AIT is in touch with the Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) to get the programme tested on the UAVs. The software has been developed by a team of scientists from the AIT's electronics and telecommunication department, including Prof J B Jawale, Prof P V Bhat, and independent consultant Mahesh Khadtare.

"The software we have developed increases the precision of the landing of the UAV to 97 per cent and does not need a human operator. This means that the scope of error in landing is only 3 per cent and this will greatly circumvent difficulties in the present landing system of UAV," said Mahesh Khadtare, the lead scientist of the project.

Instead of human operator, the landing of the UAV will be controlled by its inbuilt microprocessor. "The landing of the UAV will be controlled by the microprocessor that will recognise the already stored images of the landing space and accordingly guide the UAV for landing. The webcam of the UAV will take the pictures of landing space for the microprocessor to recognise them," said Khadtare.

AIT scientists said the software programme which they have developed will not only make the landing of UAVs precise, but also their development more cost effective. "This will be an economical system," said Prof Bhat.

"There will be no additional increase in the equipment to be fitted to the UAV. The payload will not change. The only thing that needs to be done is to convert the MATLAB software into an equivalent assembling programme for the UAV," said Khadtare.

He said the present system which is in vogue transmits the images captured by the UAV to its base station where the operator analyses the images and guides the UAV for landing.

http://www.indianexpress.com/news/ait-software-for-precise-uav-landing/641255/2

The ARMY Institute of Technology (AIT) has developed a software programme which, it claims, increases the precision in landing of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by doing away with the need for even a human remote operator.

The institute has developed a MATLAB software programme that not only increases the precision of landing of the UAVs to 97 per cent but even makes it happen automatically without these vehicles being guided by a hand-held remote. The AIT is in touch with the Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) to get the programme tested on the UAVs. The software has been developed by a team of scientists from the AIT's electronics and telecommunication department, including Prof J B Jawale, Prof P V Bhat, and independent consultant Mahesh Khadtare.

"The software we have developed increases the precision of the landing of the UAV to 97 per cent and does not need a human operator. This means that the scope of error in landing is only 3 per cent and this will greatly circumvent difficulties in the present landing system of UAV," said Mahesh Khadtare, the lead scientist of the project.

Instead of human operator, the landing of the UAV will be controlled by its inbuilt microprocessor. "The landing of the UAV will be controlled by the microprocessor that will recognise the already stored images of the landing space and accordingly guide the UAV for landing. The webcam of the UAV will take the pictures of landing space for the microprocessor to recognise them," said Khadtare.

AIT scientists said the software programme which they have developed will not only make the landing of UAVs precise, but also their development more cost effective. "This will be an economical system," said Prof Bhat.

"There will be no additional increase in the equipment to be fitted to the UAV. The payload will not change. The only thing that needs to be done is to convert the MATLAB software into an equivalent assembling programme for the UAV," said Khadtare.

He said the present system which is in vogue transmits the images captured by the UAV to its base station where the operator analyses the images and guides the UAV for landing.

http://www.indianexpress.com/news/ait-software-for-precise-uav-landing/641255/2

nandu

New Member

- Joined

- Oct 5, 2009

- Messages

- 1,913

- Likes

- 163

AIT software for precise UAV landing

AIT software for precise UAV landing

The ARMY Institute of Technology (AIT) has developed a software programme which, it claims, increases the precision in landing of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by doing away with the need for even a human remote operator.

The institute has developed a MATLAB software programme that not only increases the precision of landing of the UAVs to 97 per cent but even makes it happen automatically without these vehicles being guided by a hand-held remote. The AIT is in touch with the Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) to get the programme tested on the UAVs. The software has been developed by a team of scientists from the AIT's electronics and telecommunication department, including Prof J B Jawale, Prof P V Bhat, and independent consultant Mahesh Khadtare.

"The software we have developed increases the precision of the landing of the UAV to 97 per cent and does not need a human operator. This means that the scope of error in landing is only 3 per cent and this will greatly circumvent difficulties in the present landing system of UAV," said Mahesh Khadtare, the lead scientist of the project. nstead of human operator, the landing of the UAV will be controlled by its inbuilt microprocessor. "The landing of the UAV will be controlled by the microprocessor that will recognise the already stored images of the landing space and accordingly guide the UAV for landing. The webcam of the UAV will take the pictures of landing space for the microprocessor to recognise them," said Khadtare.

AIT scientists said the software programme which they have developed will not only make the landing of UAVs precise, but also their development more cost effective. "This will be an economical system," said Prof Bhat.

"There will be no additional increase in the equipment to be fitted to the UAV. The payload will not change. The only thing that needs to be done is to convert the MATLAB software into an equivalent assembling programme for the UAV," said Khadtare.

He said the present system which is in vogue transmits the images captured by the UAV to its base station where the operator analyses the images and guides the UAV for landing.

http://idrw.org/?p=2243#more-2243

AIT software for precise UAV landing

The ARMY Institute of Technology (AIT) has developed a software programme which, it claims, increases the precision in landing of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by doing away with the need for even a human remote operator.

The institute has developed a MATLAB software programme that not only increases the precision of landing of the UAVs to 97 per cent but even makes it happen automatically without these vehicles being guided by a hand-held remote. The AIT is in touch with the Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) to get the programme tested on the UAVs. The software has been developed by a team of scientists from the AIT's electronics and telecommunication department, including Prof J B Jawale, Prof P V Bhat, and independent consultant Mahesh Khadtare.

"The software we have developed increases the precision of the landing of the UAV to 97 per cent and does not need a human operator. This means that the scope of error in landing is only 3 per cent and this will greatly circumvent difficulties in the present landing system of UAV," said Mahesh Khadtare, the lead scientist of the project. nstead of human operator, the landing of the UAV will be controlled by its inbuilt microprocessor. "The landing of the UAV will be controlled by the microprocessor that will recognise the already stored images of the landing space and accordingly guide the UAV for landing. The webcam of the UAV will take the pictures of landing space for the microprocessor to recognise them," said Khadtare.

AIT scientists said the software programme which they have developed will not only make the landing of UAVs precise, but also their development more cost effective. "This will be an economical system," said Prof Bhat.

"There will be no additional increase in the equipment to be fitted to the UAV. The payload will not change. The only thing that needs to be done is to convert the MATLAB software into an equivalent assembling programme for the UAV," said Khadtare.

He said the present system which is in vogue transmits the images captured by the UAV to its base station where the operator analyses the images and guides the UAV for landing.

http://idrw.org/?p=2243#more-2243

LETHALFORCE

New Member

- Joined

- Feb 16, 2009

- Messages

- 29,968

- Likes

- 48,929

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/I...cted_By_USAF_Academy_To_Train_Cadets_999.html

Insitu's ScanEagle UAS Selected By USAF Academy To Train Cadets

Insitu has teamed with BOSH Global Services to train U.S. Air Force Academy cadets on the disciplines critical to planning and executing missions using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), specifically Insitu's ScanEagle, from within the Air Forces' Air Operations Center (AOC).

The training is designed to familiarize academy cadets with UAS and to give them first-hand knowledge of how these systems can be integrated into Air Force Operations to support warfighters worldwide.

"ScanEagle was chosen because it is a superior system that is extremely intuitive, giving cadets a hands-on learning experience almost from day one," said U.S. Air Force Academy Lt. Col. David Latham. "This UAS is perfect for training at the academy because of its high-performance capacity at higher altitudes and extreme temperatures."

"The Air Force is training more cadets to become UAS pilots to keep pace with the worldwide demand for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities. At a fraction of the cost of larger UAS platforms, the ScanEagle provides a cost-effective and efficient option for the Air Force to train cadets how to achieve their core competencies of information superiority, global attack and agile combat support," said Vice President, Sustainment Operations and General Operations Mary Margaret Evans.

Through the program, cadets get hands-on experience in the operation of UAS. They also receive instruction about intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, aerodynamics, mission planning, emergency procedures, visual observer duties and techniques and airmanship concepts.

The basic UAS course lasts eight days. On the first instruction day, cadets get an overview and watch a demonstration of ScanEagle in flight. The rest of the training, offered by BOSH, involves in-class and actual flight operations instruction.

Each student operates ScanEagle during six 40-minute training periods of actual flight. This year, three courses are offered: basic, advanced and instructor preparation.

The instructor prep course was conducted in April when 24 upper-level cadets received instruction to help train lower-level cadets. In June, about 90 cadets are participating in the basic course. The advanced session will be offered in the fall.

Insitu's ScanEagle UAS Selected By USAF Academy To Train Cadets

Insitu has teamed with BOSH Global Services to train U.S. Air Force Academy cadets on the disciplines critical to planning and executing missions using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), specifically Insitu's ScanEagle, from within the Air Forces' Air Operations Center (AOC).

The training is designed to familiarize academy cadets with UAS and to give them first-hand knowledge of how these systems can be integrated into Air Force Operations to support warfighters worldwide.

"ScanEagle was chosen because it is a superior system that is extremely intuitive, giving cadets a hands-on learning experience almost from day one," said U.S. Air Force Academy Lt. Col. David Latham. "This UAS is perfect for training at the academy because of its high-performance capacity at higher altitudes and extreme temperatures."

"The Air Force is training more cadets to become UAS pilots to keep pace with the worldwide demand for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities. At a fraction of the cost of larger UAS platforms, the ScanEagle provides a cost-effective and efficient option for the Air Force to train cadets how to achieve their core competencies of information superiority, global attack and agile combat support," said Vice President, Sustainment Operations and General Operations Mary Margaret Evans.

Through the program, cadets get hands-on experience in the operation of UAS. They also receive instruction about intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, aerodynamics, mission planning, emergency procedures, visual observer duties and techniques and airmanship concepts.

The basic UAS course lasts eight days. On the first instruction day, cadets get an overview and watch a demonstration of ScanEagle in flight. The rest of the training, offered by BOSH, involves in-class and actual flight operations instruction.

Each student operates ScanEagle during six 40-minute training periods of actual flight. This year, three courses are offered: basic, advanced and instructor preparation.

The instructor prep course was conducted in April when 24 upper-level cadets received instruction to help train lower-level cadets. In June, about 90 cadets are participating in the basic course. The advanced session will be offered in the fall.

- Joined

- May 26, 2010

- Messages

- 31,122

- Likes

- 41,041

AURA looks nice..

But i hope to see Nishant modified version with jet carrying PGMs for now..

if that possible..

But i hope to see Nishant modified version with jet carrying PGMs for now..

if that possible..

LETHALFORCE

New Member

- Joined

- Feb 16, 2009

- Messages

- 29,968

- Likes

- 48,929

http://www.domain-b.com/defence/general/20100703_operations.html

DRDO-IIT Powai team develops 'Netra' to aid in anti-terror operations news

The Pune-based Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has developed an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for aiding in anti-terrorist and counter insurgency operations. The UAV called 'Netra' would be inducted into the armed forces by the year-end.

The Netra, which weighs 1.5 kg, is the result of a collaborative effort between ideaForge, a company formed by a group of IIT, Powai alumni and one of the labs of DRDO, Research and Development Establishment (Engineers) (R&DE) Pune.

DRDO scientist Dr Alok Mukherjee, who demonstrated the UAV in Pune, yesterday, said the device would likely be introduced within the next six months after it had undergone some more testing.

"The UAV is capable of operating in all the conflict theatres, including urban quarters, in a situation similar to that of the 26/11 terror attacks," he told reporters.

According to Mukerjee, the Netra's estimated cost is Rs20 lakh, but this price could vary with incorporation of additional components like thermal camera as required.

Amardeep Singh, IdeaForge, vice-president (marketing and operations unmanned systems), said the UAV had been designed for surveillance of an area of 1.5 km Line of Sight (LOS) and with an endurance capacity of 30 minutes of battery charge.

Additionally, Netra also comes with a resolution CCD camera with a pan/tilt and zoom capability for wider surveillance and can also be fitted with thermal cameras to carry out night operations.

According to Singh, the operational altitude of the UAV is 200 metres maximum, and it has a vertical take-off and landing capacity (VTOL). It is equipped with a wireless transmitter. Its in-built fail-safe features allow Netra to return to base on loss of communication or low battery.

Responding to a question about the weather conditions in which it could operate, Singh said the device would not be able to operate in rainy conditions but research is being carried out to allow this.

DRDO-IIT Powai team develops 'Netra' to aid in anti-terror operations news

The Pune-based Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has developed an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for aiding in anti-terrorist and counter insurgency operations. The UAV called 'Netra' would be inducted into the armed forces by the year-end.

The Netra, which weighs 1.5 kg, is the result of a collaborative effort between ideaForge, a company formed by a group of IIT, Powai alumni and one of the labs of DRDO, Research and Development Establishment (Engineers) (R&DE) Pune.

DRDO scientist Dr Alok Mukherjee, who demonstrated the UAV in Pune, yesterday, said the device would likely be introduced within the next six months after it had undergone some more testing.

"The UAV is capable of operating in all the conflict theatres, including urban quarters, in a situation similar to that of the 26/11 terror attacks," he told reporters.

According to Mukerjee, the Netra's estimated cost is Rs20 lakh, but this price could vary with incorporation of additional components like thermal camera as required.

Amardeep Singh, IdeaForge, vice-president (marketing and operations unmanned systems), said the UAV had been designed for surveillance of an area of 1.5 km Line of Sight (LOS) and with an endurance capacity of 30 minutes of battery charge.

Additionally, Netra also comes with a resolution CCD camera with a pan/tilt and zoom capability for wider surveillance and can also be fitted with thermal cameras to carry out night operations.

According to Singh, the operational altitude of the UAV is 200 metres maximum, and it has a vertical take-off and landing capacity (VTOL). It is equipped with a wireless transmitter. Its in-built fail-safe features allow Netra to return to base on loss of communication or low battery.

Responding to a question about the weather conditions in which it could operate, Singh said the device would not be able to operate in rainy conditions but research is being carried out to allow this.

plugwater

New Member

- Joined

- Nov 25, 2009

- Messages

- 4,154

- Likes

- 1,082

IAF Floats UCAV Procurement Bid

The Indian Air Force has published a request for information (RFI) for an unspecified number of unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs). The IAF says it's looking for a modern high-endurance single/twin engine stealthy UCAV, with a satellite data link and an internal weapons payload, in other words just like AURA, India's indigenous UCAV programme.

http://livefist.blogspot.com/2010/0.../UQMw+(LiveFist+-+The+Best+of+Indian+Defence)

The Indian Air Force has published a request for information (RFI) for an unspecified number of unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs). The IAF says it's looking for a modern high-endurance single/twin engine stealthy UCAV, with a satellite data link and an internal weapons payload, in other words just like AURA, India's indigenous UCAV programme.

http://livefist.blogspot.com/2010/0.../UQMw+(LiveFist+-+The+Best+of+Indian+Defence)

LETHALFORCE

New Member

- Joined

- Feb 16, 2009

- Messages

- 29,968

- Likes

- 48,929

http://www.defensenews.com/story.php?i=4693946&c=AIR&s=TOP

Qinetiq Seeks Record-Breaking Test Flight For Zephyr UAV

British defense research company Qinetiq is expected to launch a new version of its Zephyr solar-powered unmanned vehicle in the next few days on what it hopes will be a record-breaking test flight.

The aspiration is to turn the flight into a multiweek operation to demonstrate the Zephyr's ability to act as a persistent communications relay or surveillance platform for the military. (QINETIQ)

Officially, the machine - known as the Zephyr 7 - is trying for the 33.1 hours world unmanned flight record, held by Northrop Grumman's Global Hawk since 2008.

More importantly, said program officials, the aspiration is to turn the flight into a multiweek operation to demonstrate the Zephyr's ability to act as a persistent communications relay or surveillance platform for the military.

Qinetiq is waiting for flight clearance for the Zephyr to get the test flight underway. That could happen any day now.

If things go according to plan, the high altitude, long endurance Zephyr should pass the Global Hawk milestone with ease.

The UAV has already flown more than 82 hours in 2008 but failed to secure the record because FAI officials were not present.

Now, Qinetiq reckons the upcoming test flight from the U.S. Army proving ground at Yuma, Ariz., could see the machine airborne for as long as two weeks.

Paul Davy, the Zephyr business development director, said the ultimate target for the machine is to regularly conduct missions of up to three months.

"The reason for this latest test flight is to prove we can fly for a long duration. Eventually we will be shooting for three months", he said.

Aside from the endurance effort, the Qinetiq machine will carry a British Ministry of Defence communications relay payload for testing.

The MoD and the U.S. Naval Air Systems Command will both have observers at the demonstration flight, said a Qinetiq spokesman.

Zephyr has already been looked at by the Pentagon under its Joint Capability Technology Demonstration program.

Much of the funding for development has been provided by the MoD, and Davy said that depending on progress, "there is a strong possibility the MoD could become an early customer."

The Qinetiq executive said he expected communications relay would likely be the first application for Zephyr, although the machine potentially has a range of surveillance and other roles in military and civilian markets.

The aircraft being flown by Qinetiq sports several significant improvements from earlier versions. Most noticeable is the addition of a winglet giving lower drag characteristics. The result is a 22-meter-long wing rather than the earlier 18-meter wingspan. Other changes include modifications to the propellers and to the way the aircraft's batteries are controlled and power stored.

The carbon-fire-structured machine flies during the day using solar power generated by paper-thin amorphous silicon arrays covering the wings.

During the night, power is provided by rechargeable lithium-sulphur batteries.

Qinetiq Seeks Record-Breaking Test Flight For Zephyr UAV

British defense research company Qinetiq is expected to launch a new version of its Zephyr solar-powered unmanned vehicle in the next few days on what it hopes will be a record-breaking test flight.

The aspiration is to turn the flight into a multiweek operation to demonstrate the Zephyr's ability to act as a persistent communications relay or surveillance platform for the military. (QINETIQ)

Officially, the machine - known as the Zephyr 7 - is trying for the 33.1 hours world unmanned flight record, held by Northrop Grumman's Global Hawk since 2008.

More importantly, said program officials, the aspiration is to turn the flight into a multiweek operation to demonstrate the Zephyr's ability to act as a persistent communications relay or surveillance platform for the military.

Qinetiq is waiting for flight clearance for the Zephyr to get the test flight underway. That could happen any day now.

If things go according to plan, the high altitude, long endurance Zephyr should pass the Global Hawk milestone with ease.

The UAV has already flown more than 82 hours in 2008 but failed to secure the record because FAI officials were not present.

Now, Qinetiq reckons the upcoming test flight from the U.S. Army proving ground at Yuma, Ariz., could see the machine airborne for as long as two weeks.

Paul Davy, the Zephyr business development director, said the ultimate target for the machine is to regularly conduct missions of up to three months.

"The reason for this latest test flight is to prove we can fly for a long duration. Eventually we will be shooting for three months", he said.

Aside from the endurance effort, the Qinetiq machine will carry a British Ministry of Defence communications relay payload for testing.

The MoD and the U.S. Naval Air Systems Command will both have observers at the demonstration flight, said a Qinetiq spokesman.

Zephyr has already been looked at by the Pentagon under its Joint Capability Technology Demonstration program.

Much of the funding for development has been provided by the MoD, and Davy said that depending on progress, "there is a strong possibility the MoD could become an early customer."

The Qinetiq executive said he expected communications relay would likely be the first application for Zephyr, although the machine potentially has a range of surveillance and other roles in military and civilian markets.

The aircraft being flown by Qinetiq sports several significant improvements from earlier versions. Most noticeable is the addition of a winglet giving lower drag characteristics. The result is a 22-meter-long wing rather than the earlier 18-meter wingspan. Other changes include modifications to the propellers and to the way the aircraft's batteries are controlled and power stored.

The carbon-fire-structured machine flies during the day using solar power generated by paper-thin amorphous silicon arrays covering the wings.

During the night, power is provided by rechargeable lithium-sulphur batteries.

| Thread starter | Similar threads | Forum | Replies | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

IAF HAWK 132 as Unmanned aerial combat vehicle | Indian Air Force | 0 | |

|

|

Cronshtadt Orion Lite MALE UAV/UCAV Platform | Military Aviation | 4 | |

|

|

India's Current & Future UAVs & UCAVs | Indian Air Force | 949 | |

|

|

Chinese UAV and UCAV News & Updates | China | 28 |

Articles

-

India Strikes Back: Operation Snow Leopard - Part 1

- mist_consecutive

- Replies: 9

-

Aftermath Galwan : Who holds the fort ?

- mist_consecutive

- Replies: 33

-

The Terrible Cost of Presidential Racism(Nixon & Kissinger towards India).

- ezsasa

- Replies: 40

-

Modern BVR Air Combat - Part 2

- mist_consecutive

- Replies: 22

-

Civil & Military Bureaucracy and related discussions

- daya

- Replies: 32