Raising a swarm

The armed forces, behind the curve on weaponised drones, are rushing to fill the gap through imports. The tougher ask, though, is to develop an indigenous ecosystem for these must-have platforms.

ndia’s military standoff with China in Ladakh, now in its sixth month, has resulted in an increased focus on equipping the armed forces. One piece of hardware has topped the acquisition wishlist of all three branches of the armed forces, drones. The urgency with which these weapons systems are now being acquired, via fast-track purchases and deliveries in months, not years, speaks of the growing importance being attached to these force multipliers.

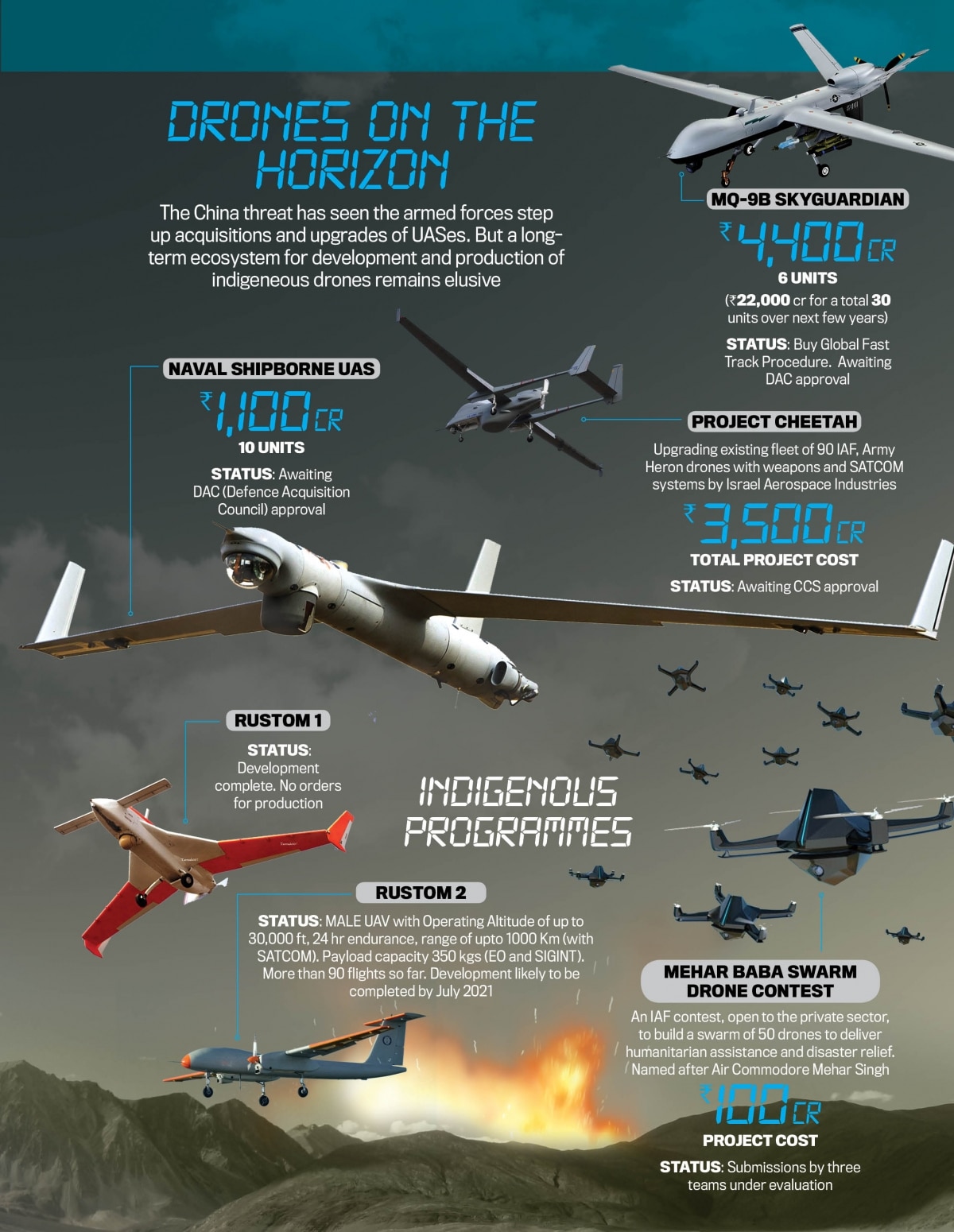

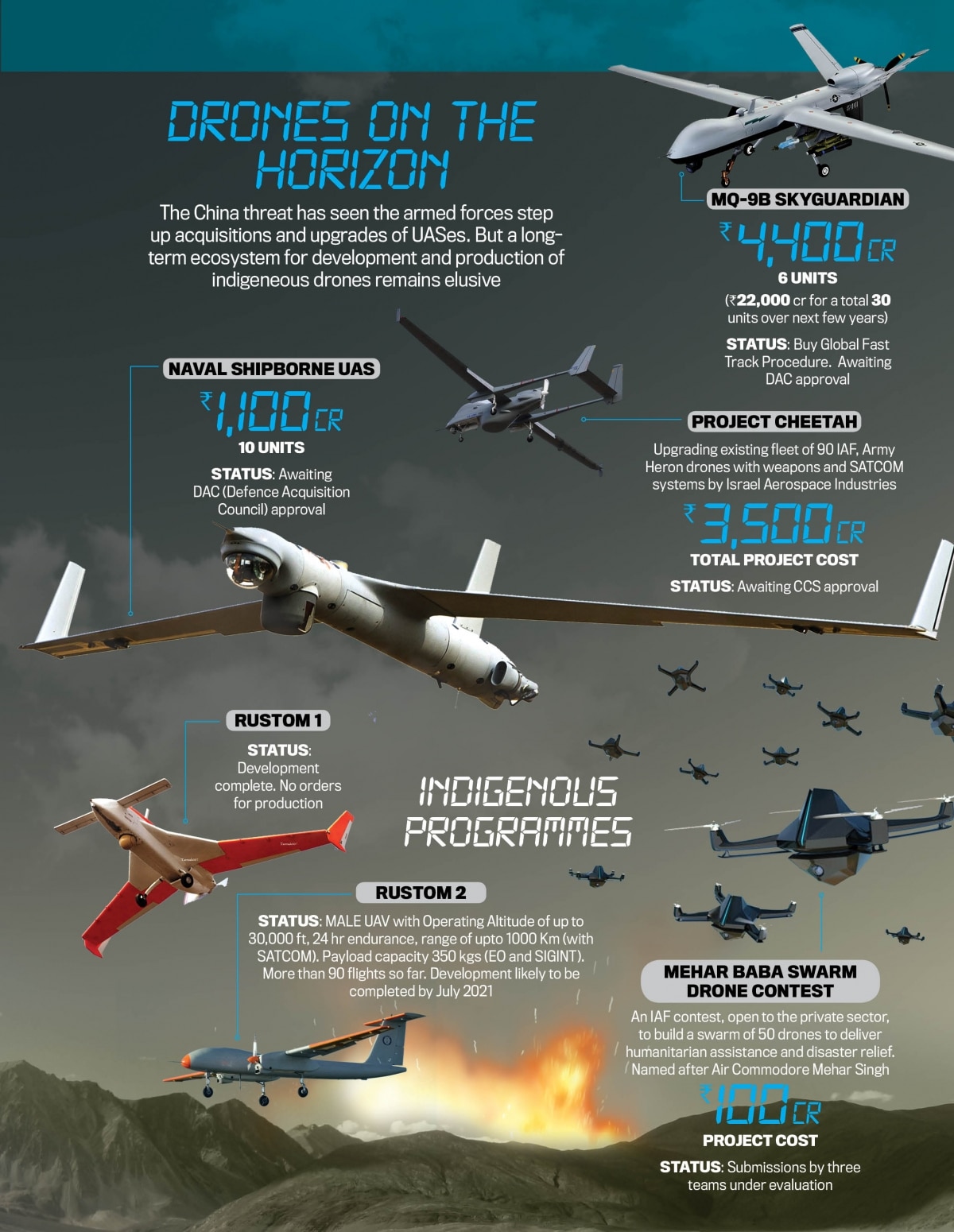

The army is looking for man-portable surveillance drones that can operate at the rarefied altitudes of its northern theatre. It also wants bigger, armed drones that can target terrorist camps across the Pakistani border with precision missiles. The navy hopes to close a fast-track contract to acquire 10 UASes (unmanned aerial systems) that can operate off its warships, before the end of the financial year. The three services will get their first weaponised drones in an off-the-shelf purchase of six MQ-9B Sky Guardians from the United States. The deal is worth over Rs 4,000 crore, with an option to buy 18 more over the next few years. The contract closest to being signed, however, is the Rs 5,500 crore Project Cheetah, to upgrade the ‘Heron’ medium-altitude long-endurance drone fleet with all three services. The defence ministry has finished price negotiations with Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) for the upgrade, this will convert the fleet of primarily ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) drones, acquired over a decade ago, into weapons platforms. The project, which will equip them with satellite navigation, air-to-ground missiles and precision weapons, is awaiting sanction from the cabinet committee on security (see Drones on the Horizon). These proposals will see the armed forces collectively spending close to Rs 36,000 crore ($5 billion) over the next few years.

Drones, both armed and unarmed, have been a feature of major wars in Asia and Africa in recent years, from ISIS in Syria rigging small drones to drop grenades to the ongoing civil war in Libya, where both sides have been using combat drones. Drone technology has also seen a steady increase in sophistication and effectiveness. The attack on Saudi Aramco oil refineries on September 14, 2019, attributed to Houthi rebels in Yemen, showed both their lethality and the ease with which even non-state actors can make use of them. The ongoing war between Azerbaijan and Armenia, the first armed conflict between two countries in over a decade, has demonstrated the devastating potential of drones in uncontested airspace. Azerbaijan’s fleet of Turkish-built armed UASes have pulverised tanks, trucks and fortifications. Armed drones, clearly, are the force multipliers of today, not of some distant battlefield of tomorrow.

In India, along the tense frontiers of the subcontinent, both Pakistan and China are using drones with increased frequency. Over the past 13 months, security forces in Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have intercepted five drone ‘mules’, operated by Pakistan’s ISI (Inter Services Intelligence), ferrying weapons and ammunition to Khalistani and Kashmiri terrorists. The Chinese PLA (People’s Liberation Army) has an array of tactical surveillance drones for snooping on Indian positions in Ladakh. Chinese Communist Party mouthpieces routinely publish propaganda videos of their new unmanned helicopter drones, optimised for high-altitude operations, performing mundane tasks, such as delivering hot food to troops.

The Indian armed forces’ drone acquisitions have been long in the pipeline. With indigenous programmes slow to materialise, foreign firms have captured India’s market for these weapons platforms. Even so, progress has been slow. Project Cheetah was approved by the defence acquisition council (DAC) nearly a decade ago, in 2011. And in 2015, the navy had put out a request for information (the first step in an acquisition) for naval shipborne UASes. These are urgently required, especially for non-combat missions. Platforms like the MQ-9B Guardian will allow the armed forces to reduce running costs on tasks like distant maritime surveillance and patrolling the land borders. “The MQ-9B is satellite-steered, can float above the target at 45,000 feet and stay on task for 35 hours, using radar and electronic support measures to locate the enemy. It [can be used] anywhere, the Gulf of Aden or the Malacca Straits or in Ladakh,” a senior defence official says. Each one costs close to Rs 900 crore, the reason at least one of the three services is believed to have had second thoughts on acquiring them. But these off-the-shelf imports, with zero transfer of technology, come with other costs. They ensure continued import dependency on Israel, and now, the United States.

It is in the category of HALE and MALE (high-altitude and medium-altitude long-endurance) UASes that the voids are most glaring (see Handheld to High Altitude). There are currently no indigenously designed or built short- or medium-range surveillance drones in the Indian armed forces’ inventory. The DRDO’s (Defence Research and Development Organisation’s) Rustom 1 has no orders. The Rustom 2, meant to be an alternative to the Israeli MALE Heron, is still in development. The platform has had two successful flights this year and the DRDO is hopeful of a breakthrough by next year.

India’s fledgling group of drone developers can only watch these developments with dismay. As one developer says, India’s R&D spending on drone technologies is not even equal to the annual maintenance costs of the fleet of imported systems. For the armed forces, indigenous drones hold out not only the potential of becoming force multipliers, but with budgetary cuts, as a low-cost solution to meet operational requirements. “Military aviation comes at a huge cost, the navy, the Cinderella service (its 15 per cent share is the smallest of the defence budget), has to be extremely thrifty. Unmanned surveillance gives us a huge tactical advantage on the seas, which satellite and aircraft-based surveillance don’t give us,” says Rear Admiral Sudhir Pillai, former Flag Officer Naval Aviation. While there are domestic joint ventures to build such platforms, for instance, Adani Defence has teamed up with Israel’s Elbit to build drones within the country, these will not be indigenously designed or developed. “We are drone assemblers, not UAS developers,” says a private sector drone maker.

The DRDO has been slow to meet the requirements of the armed forces. It has succeeded in fielding pilotless target aircraft like the Lakshya but products like the Nishant short-ranged surveillance drone have had a tardy record with the services.

The DRDO has had more success in developing mini and micro UAVs. It says it has transferred dronetechnology to industry partners for various systems and established them as aerospace industries for supplying sub systems and components. In 2010, the DRDO and the Department of Science and Technology funded the National Programme for Micro Air Vehicles (NP-MICAV) to promote R&D in mini and micro UAVs. The organisation says it has left the development of these small UAVs to industries and academia while it focuses on MALE, HALE and weaponised UAVS.

A 2019 FICCI and EY report projects the Indian civilian UAS market to touch $885.7 million (Rs 6,500 crore) by 2021 on the back of their utility in infrastructure, photography and agriculture. There are no estimates for the military and security forces, but this would be larger. The lack of a long-term acquisition plan or a roadmap, a version of the integrated guided missile development programme for drones, means there is virtually no indigenous ecosystem for UASes. Worse, all the major components for lightweight drones, the auto-pilot or the brain of the machine, the battery pack, the motherboard and the propellers and motors, are imported, the majority from the world leader in drones, China.

“There is a need for an integrated development program, but before that it is essential to identify their role and how they fit into future war fighting tactics,” says Lt General D.S. Hooda, former Northern Army Commander. “Right now we are buying what is available rather than what could be needed, for example, the Guardian. Initially it was proposed for the Navy and then all three services wanted it. We need to procure based on the operational requirements.” Future war is based on electronics, software and sensors. The combat drone, developers say, is all of that. “Why just drones, the technology that would be developed can be used in a range of situations, from unmanned ground vehicles to naval applications,” says a drone developer, who requested anonymity.

There is exactly one project which currently holds out a glimmer of hope for futuristic military projects, the Mehar Baba Swarm Drone Competition, an IAF-funded project for creating swarm drones. The winner of the contest to build a fleet of 50 drones to deliver humanitarian assistance and disaster relief will bag a Rs 100 crore IAF contract.

But such projects, which bring in the brightest in Indian industry, are few and far between. The question, as always, is who will fund these projects. “Our systems are process-oriented and not goal-oriented,” says Sameer Joshi, a former IAF fighter pilot who is part of a team of developers who are in the contest for the project. Developers point to Turkey, which has built up an ecosystem over the past 15 years and is now a world leader in armed drones. Turkish armed drones have tipped the scales in virtually every recent conflict in its extended neighbourhood, from Syria and Libya to Nagorno Karabakh. It might only be a matter of time before drones appear in our neighbourhood too, as a wake-up call.

That remotely piloted aircraft systems are here to stay is a given. They could potentially have the same impact on warfare that digital networks and precision-guided weapons, unveiled during the Gulf War of 1991, did. Inexpensive, mass-produced drones under development in defence labs across the world can swarm against, and cripple, expensive military hardware like fighter jets and surface-to-air missile batteries.

A 2020 study prepared by US think-tank RAND predicts that low-cost ‘meshed’ UASes will greatly reduce the number of weapons required to destroy targets. For instance, to thwart a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, it estimates that 10,000 Harpoon class weapons (an anti-ship missile) would be required to destroy 72 per cent of an invading flotilla’s ‘tank equivalent’ capacity carried by landing craft. A targeting mesh of 600 or more cheap, mass-produced UAS weapons can destroy upwards of 80 per cent of the same flotilla.

The armed forces, behind the curve on weaponised drones, are rushing to fill the gap through imports. The tougher ask, though, is to develop an indigenous ecosystem for these must-have platforms.

www.indiatoday.in

.

.