Chinese Navy Destroyers

- Thread starter SexyChineseLady

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?rockdog

New Member

- Joined

- Dec 29, 2010

- Messages

- 4,249

- Likes

- 3,025

Dalian simultaneously launching from one dock is not something we would see every day. Probably set to receive modules for another pair. I think it is no more than a year since satellite pictures identified two keels being laid down in Dalian, and still more to come from Shanghai.

CSIC have launched four of these cruisers since June of last year. Two yards spitting them out concurrently. They launch with the entire superstructure in place. IN launch much less finished vessels.

This was the P15B Visakhapatnam during launch:

I think CSIC did is more efficient. Multiple shipyards building one class, two ships in one dock, superstructures are completed in drydock, simultaneous launchings, simultaneous fitting out, etc.

CSIC have launched four of these cruisers since June of last year. Two yards spitting them out concurrently. They launch with the entire superstructure in place. IN launch much less finished vessels.

This was the P15B Visakhapatnam during launch:

I think CSIC did is more efficient. Multiple shipyards building one class, two ships in one dock, superstructures are completed in drydock, simultaneous launchings, simultaneous fitting out, etc.

Last edited:

J20!

New Member

- Joined

- Oct 20, 2011

- Messages

- 2,748

- Likes

- 1,546

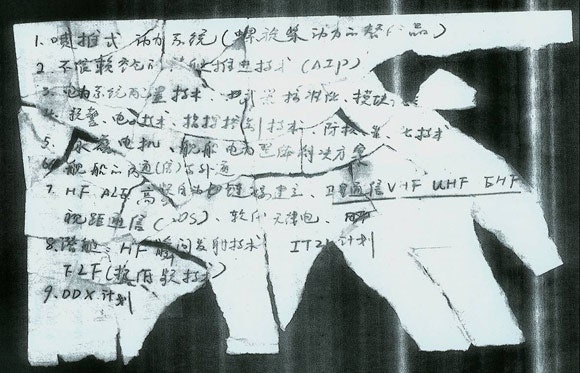

A well referenced article by US Navy Captain Dale C. Rielage detailing trends in Chinese Navy training and recruitment trends from Proceedings Magazine.How many years of training do the sailors go through to operate such ships. And how are they even drafted.

I've tried to highlight the portions most relevant to your question.

Chinese Navy Trains and Takes Risks

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2016-05/chinese-navy-trains-and-takes-risks

Improvements in Chinese Navy multi-mission platforms have seen a focus on realistic training.

In the past decade, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has added significant new capabilities to its order of battle. The average PLAN surface combatant is now a capable, multi-mission platform. The PLAN submarine force is increasingly composed of modern conventional and nuclear units, many employing long-range antiship cruise missiles. The aircraft carrier Liaoning continues steady work as China learns the art and science of naval aviation.

Hardware, however, defines the limits of what is technically possible for a navy. Effectiveness in combat rests on proficiency in employing the tools at hand, and the PLAN understands that fact. The past ten years have seen a major improvement in the scope and complexity of PLAN training that has paralleled the expansion in its missions, operations, and capabilities. This substantial training program is intended to ensure that the PLAN’s expanding arsenal of high-technology weapons can be employed to carry out the missions the PLAN has been given by the ruling Chinese Communist Party. Central to these are high-end naval combat tasks—the fundamentals of fleet action against a foreign navy intervening against People’s Republic of China (PRC) interests. While no training is a perfect facsimile of combat, the PLAN’s proficiency is increasing through this deliberate investment in more advanced and realistic training.

The depth and sophistication of public analysis of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has grown in recent years, reflecting a need to understand the PLA’s modernization and ability to intervene in an increasing range of potential friction points. PLA training has been a part of these studies, but most works have involved changes in the senior-level structures that administer training and on PLA efforts to train for joint warfare. PLA leadereship has concentrated on making training more effective and more “joint,” and the PLAN has benefited from changes in these areas. 1 However, while these issues are essential, they do not speak to the basic question of how the PLAN trains itself.

Guidance from the Top: Realism Matters

In China, “army building”—the modernization and effectiveness of the PLA—is an issue that involves the most senior levels of the party leadership. Early in his tenure, General Secretary Xi Jinping has made it clear that achieving the “China Dream” that defines his legacy includes the “dream of having a strong army.” 2 Achieving a strong military is a national-level priority. Senior leaders convey their emphasis on it in the high-level party documents that outline the PLA’s missions, its broad goals for modernization, and priorities for investment, placing a heavy emphasis on achieving “informatization” and jointness. To support these efforts, in 2011 the PLA General Staff Department formed a Military Training Department. The reorganized department received a renewed and expanded mandate to guide Navy, Air Force, and Second Artillery training. 3

The series of documents known as the “Outline on Military Training and Evaluation” (OMTE) provide the most direct guidance to PLA training. The senior-level OMTE is issued by the General Staff Department (GSD). It can be inferred from public discussions that an OMTE exists for each level of the PLA, from PLA-wide to the individual service down to the unit level. 4

The OMTE appears to be the basis for determining a unit’s training tasks across all phases of readiness. Officers are expected to be conversant in its requirements and are examined on them regularly. In 2014, the PLAN Submarine Academy shifted from using a series of in-house documents as their training texts to employing only the submarine service OMTE as the basis of training. At the same time, academy examinations began to be prepared by examiners from fleet units rather than academy staff, with the academy training staff not knowing the content of the examinations prior to their administration. 5 One of the tasks associated with commissioning any new class of warship into the PLAN is the development of an OMTE for the new platform.

Unit-Level Execution

It is worth noting that some dated sources indicate the PLAN follows a training cycle based on the annual influx of new draftees into the fleet. For much of the PLAN’s history, autumn brought with it a training reset, as new recruits arrived and were taught basic seamanship skills on board their assigned vessels. As this cadre grew in knowledge and experience, the units could move on to more complex evolutions, culminating in maximum readiness just before one draft group was discharged and a new draft class arrived. In recent years, the PLAN has made recruiting a more highly educated enlisted force—including college graduates—a priority. At the same time, the percentage of draftees on PLAN afloat units has dropped, replaced by a growing number of enlisted personnel under long-term contracts. This shift has freed the PLAN from the annual training cycle and allowed for a shift to a more consistent level of readiness throughout the year. 6

In order to join fleet operations, new-construction units and units leaving a major repair period are required to be trained and passed by their respective fleets’ Vessel Training Center (VTC). These units were established in the mid-1980s. Prior to the early 2000s, their training courses consisted of a year-long curriculum that commenced only once per year. The current construct allows units to begin at any point, completing a tailored syllabus that fulfills the tasks required by their specific OMTEs. 7 The mandate of the VTCs appears broad. They employ simulators, and some of the certifications appear to resemble combat team-trainers with multiple units participating and being evaluated simultaneously. In other cases, the VTC provides at-sea training using embarked teams.

To support introducing the first Jiangdao-class (Type 056) corvette, the Bengbu , into service, the East Sea Fleet VTC organized a team of experts from active PLAN units and industry to develop the class training plan and to guide the ship through it. Notably, the VTC enlisted three captains with experience in counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden to mentor the crew. In the process, the VTC developed an OMTE for the class of more than 1,000 pages. The entire process from the Bengbu ’s commissioning to completion of training took seven months. 8

At all levels of the PLA, training is “party work.” While many U.S. observers assume the Communist Party structure restricts its efforts to political education and ensuring loyalty, the party apparatus routinely manages what it sees as the most critical operational elements of the PLA. From the highest levels of the PLAN to the individual unit, the details of the training plan are reviewed and approved by that command’s party committee. It is likely that the OMTE serves as the basic reference for formulating this training plan.

Despite a higher-level guidance, there is clearly a place for unit-level initiative. One PLAN air-defense unit being held up as an example indicated that part of such units’ success lay in adding training topics to their plan beyond those already required by higher headquarters. When units are criticized, it is typically for their training not following closely enough the demands of actual combat. The Jiangkai II–class (Type 054A) frigate Liuzhou was criticized for failing a combat-readiness inspection because the crew had not drilled with live ammunition. When tested with live rounds, the additional steps involved in handling the potentially hazardous ordnance caused the ship to exceed the time standard for the drill. Meanwhile, units that compound the difficulty of their training are praised publicly. During one training event, the Luyang II–class (Type 052C) destroyer Haikou shifted from radar to optical guidance while engaging a floating target with surface guns, increasing the difficulty of the evolution. What is more significant is that the ship reportedly did this during a recent Sino-Russian exercise, implying the unit commander was more concerned with training value than the potential of not performing well under the eyes of a foreign navy. 10

Once approved, implementation of the plan is the responsibility of the unit. For units in active service, the flotilla appears to fulfill the key role of training administration and oversight. In some cases, this oversight appears to be pervasive and invasive by U.S. standards.

There are, however, signs that this tradition of close oversight is shifting. Within the PLAN submarine force, units have been praised for “making voyages in accordance with authorized strength”—a euphemism for conducting significant operations without additional senior-level personnel on board. The submarine force noted that the routine presence of senior-level leaders had eroded the authority of the commanding officers, creating a culture where “the captain functioned as a duty officer, and the duty officer became a messenger.” Reversing this trend required specific additional training for commanders and executive officers, including in-port drills and scenario trainers that “forced individual ship commanders to act spontaneously and . . . independently.” Notably, this change did not involve a change to regulations, but a change to command culture. Both the identification of the problem and the efforts to solve it were led by the unit’s party committee. 11

Distant-Seas Training and Exercises

These are two related aspects of the PLAN’s overall training improvement. Distant-seas training, meaning training operations conducted beyond the First Island Chain, can be part of an exercise but are more commonly group-sailing evolutions intended to showcase capability and develop proficiency in operations at distance from the Chinese mainland.

The PLAN notes that distant-seas training began in 2008 and has become a regular part of the PLAN’s training plan. 12 At the 2015 PLAN Party “Grassroots Meeting,” the PLAN reported that 90 ships in 21 groups have operated “in far seas”—generally meaning beyond the First Island Chain—during the previous three years. 13 While December 2008 also saw the first PLAN task force depart for counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, this move toward more distant training preceded the deployment and was not directly related to the new mission but rather the implementation of distant-seas defense tasks across the PLAN.

Large-scale training involving multiple fleets or “campaign-level” training is supervised by the PLAN Headquarters Training Department. As part of the PLAN’s efforts to build regional acceptance of its growing naval presence, the Headquarters Department consistently emphasizes that these major operations are routine and conducted “in accordance with the annual training plan” and “directed against no nation.”

During summer 2015, the PLAN conducted several major exercises that received extensive coverage in both official and unofficial media outlets. From these articles, we can see a number of common characteristics increasingly shared by major PLAN exercises regardless of their distance from the mainland.

Multiple Fleets. PLAN exercises now incorporate units from all three operational PLAN fleets. In some cases, one fleet will act as the opposing force for another, while in other cases the various fleets integrate as part of a single force. Either way, this routine movement of units among fleets implies an increasing level of standardization and interoperability.

Integration of Multiple Warfare Elements. The PLAN officially includes five warfare communities—surface, submarine, air, coastal defense (i.e., coastal defense cruise-missile units), and marine corps—which participate in all major exercises. Beyond PLAN forces, there is an increasing joint element in these events. It is unclear if these are designated officially as “joint” exercises or if, as appears more likely, joint elements are increasingly being integrated into what are primarily naval and navy-led exercises. Integration of PLA Air Force (PLAAF) units appears to be most common, but elements of the various military regions, likely army, are also mentioned. At least one South Sea Fleet exercise in summer 2015 included integration of several Second Artillery (since renamed “PLA Rocket Force”) missile battalions. 14

Live “Blue” (Opposing) Force. In 2013, PLA ground forces in the Beijing Military District created a dedicated “blue force” that functions as an opposition force in training. In the PLA, opposing forces are referred to as “blue” while friendly forces are “red” in a direct reversal of U.S. convention. Similar blue units appear to exist in the PLAAF, and the PLAN Air Force (PLANAF) has also developed dedicated opposition forces for tactical training. 15 In exercises at sea, a group of ships is commonly designated to act as the opposing force for the period of the exercise, rather than a permanently dedicated group.

“Back-to-Back” Confrontation. In Chinese parlance, a “back-to-back” exercise begins with neither the red nor blue forces knowing the exact composition or disposition of the adversary. Almost every major PLAN exercise or training event in recent years has been touted as a “back-to-back” evolution, implying a significant increase in complexity and a growing emphasis on the unit commander’s ability to respond dynamically to sudden and uncertain situations.

Integration of Electromagnetic Warfare (EMW). The PLA has placed an enormous emphasis on training for operations in a “Complex Electromagnetic Environment.” Accounts of PLAN exercises not only speak in generalities about electromagnetic warfare, but specific challenges that Red encountered. In these accounts, communications fail and radars are jammed at key moments. The praiseworthy Red force responds and overcomes these attacks, or at the least, emerges more capable of surmounting them in the future. Joint units are used to support this training, as the South Sea Fleet noted integrating Guangzhou Military Region-subordinate electronic countermeasure units into its training in 2015. 16

‘Live Fire’

Not all PLAN exercises include a live-fire phase. However, live-fire evolutions routinely receive extensive press coverage, including photos. The PLAN does not publish specific numbers of ammunition expended in training (and, in fairness, neither does the U.S. Navy), but reporting from the 2015 PLAN Party “Grassroots Meeting” cited “hundreds” of missiles fired in a three-year period. 17 Generally when these launches appear in the press, they are characterized as training events rather than developmental testing, and it is doubtful that developmental events would be disclosed to the public in the same way. The impression across these sources is that the PLAN is putting a large number of weapons down-range. While the number of weapons fired is not an absolute indicator of proficiency (the Soviet Navy, for example, was noted for its large-scale live-fire exercises), it is an indicator both of the resources available for training and PLAN confidence in the fundamentals of weapon employment.

Another factor in training realism is willingness to accept risk during training. For example, a North Sea Fleet minesweeping unit was cited for exercising setting and sweeping live mines, accepting increased risk for added realism. 18 In other cases, the lack of information provided to the participants in “back-to-back” exercises suggests that few firmly defined safety parameters are set. It is notable that where official PLAN media sources mention risk in training, it is always commending a commander who deliberately chose to increase the risk associated with a training event. In some cases, these commanders are praised for violating the parameters of an exercise to seize victory. The clear impression is that the PLAN is more willing to accept risk in its training evolutions than its U.S. counterparts. This mindset builds realism but will likely carry a cost in both equipment and personnel.

Significant training events include efforts to collect data and lessons learned. In one recent major North Sea Fleet exercise, a 28-person assessment team provided adjudication of engagements, supported by more than 100 people gathering observations. 19 At least some flotilla-level units are developing their own lessons-learned database. One destroyer flotilla notably collected more than 300,000 elements of information based on 11 distant-sea training operations that had been applied to specific combat tasks. 20The PLAN’s counter-piracy operations are similarly exploited as a source of real-world experience and training topics. 21

Challenges to Improvement

Despite earnest efforts at improvement, the PLAN has identified a number of challenges that limit training effectiveness. In the present PLAN training environment, units and leaders are praised for candid disclosure of combat-readiness shortfalls. Not surprisingly, some have engaged in what the official media calls “problem contests,” listing deficiencies without attention to root causes or real intent to fix the issue. In some cases, “the problems shown off today were rather similar to the problems shown off yesterday.” Doing the hard work of addressing shortcomings in combat capability is ultimately “a test of the resolve and will of the Party Committee leaders” of the unit. 22

In some cases, new weapons are being introduced to the field before tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) have been fully developed. One PLAAF unit that received the first of a new type of command-and-control aircraft was praised for effectively developing the TTPs for the platform, literally “on the fly.” While this gap between hardware and TTPs is significant, what is important is that units are being praised for stepping into this gap and developing their own procedures for employing their new systems and training themselves in their use.

Finally, the scope of the change required to fully exploit new high-technology weapons is daunting for some. TTPs can change a certain amount, but changing command culture is more difficult. One new ship was noted as conducting air-defense evolutions using the traditional communications techniques familiar to its leaders, despite being equipped with a modern command-and-control system. The leadership was severely criticized by their flotilla, which noted that the “body” of the leaders had moved to informatization, but their minds remained in the mechanized world. 23 Similarly, the PLAAF unit that was praised for developing TTPs for its new command-and-control aircraft had to undergo a difficult transition from focusing unit training on pilots to concentrating training on the sensor operators who provide the aircraft’s capabilities to the fleet.

How well the PLAN has managed this challenging transition will never be fully known outside of combat. Routine operation, however, offers an indicator. During 2015, the PLAN supported operations to enforce PRC maritime claims throughout the First Island Chain, sustained continuous counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, evacuated hundreds of citizens from danger in Yemen, and concluded one counter-piracy deployment with an around-the-world cruise. These and other less headline-grabbing successes are underpinned by an institutional emphasis on training for high-end naval warfare. Indeed, there is a strong argument that success in this mission is the PLAN’s primary and defining priority. In private moments, PLAN officers often describe their force as a “young navy.” It is one, however, that knows it has much to learn and is devoting diligent attention to its lessons.

Last edited:

rockdog

New Member

- Joined

- Dec 29, 2010

- Messages

- 4,249

- Likes

- 3,025

All You Need to Know About China's New Stealth Destroyer

https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/all-you-need-to-know-about-chinas-new-stealth-destroyer/

The Type 055 adopts a conventional flared hull with distinctive stealthy features including an enclosed bow, where mooring points, anchor chains and other equipment are hidden belowdecks. The bow armament adopts a similar configuration to the 052C/D, with the main gun located most anterior, followed by a 64 cell block of VLS, and the eleven barrel H/PJ-11 30mm close in weapons system (CIWS).

The main deckhouse is similar to the proven configuration that the preceding 052D adopts, with fixed four face phased array radars (PARs) arranged for overlapping 360 degree coverage. However, the mast atop the deckhouse is a more advanced integrated mast, with sensors and datalinks integrated into a single structure.

Similarly, the amidships area and the smoke stack is a continuous single structure extending from the main deckhouse. A continuous integrated structure not only provides additional volume for various uses (such as amidships RHIB davits), but also reduces deck clutter and the ship’s associated radar cross section. The single integrated smoke stack is notable, as it appears to shield the exhausts from the ship’s gas turbines to a greater degree, likely to reduce infrared signatures and radar cross section.

Moving posteriorly, there is a 48 cell block of VLS, leading to the aft helicopter hangar structure featuring two helicopter hangars. A step structure atop this hangar was once suspected to possibly accommodate a volume search radar, but instead will likely be equipped with a small dome or other electronics. A 24 cell HHQ-10 missile CIWS and four decoy turrets are equipped atop the hangar. A large stern helipad, greater in size than that on the 052C/D destroyers, accommodates the ship’s organic helicopter complement.

There have been some reports that the Type 055 may involve aluminium in its construction, however at this stage there are no credible indicators for this suggestion.

Armament

The bulk of the Type 055’s firepower – as in all modern surface combatants – resides in its missile armament that can be judged in its VLS.

The Type 055 uses the same universal VLS on the Type 052D, but with a larger total cell count of 112. As written elsewhere, the Chinese Navy’s universal VLS can fire missiles in a cold launch method, or a hot launch using concentric canister launch. Each individual square VLS cell has a diameter of 0.85 meters, significantly greater than that of the Mk-41 VLS at 0.635 meters or even the Zumwalt class’ Mk-57 PVLS at 0.71 meters. The universal VLS comes in three lengths, the greatest being 9 meters, which is longer than the Mk-41’s largest strike length variant at 7.7 meters or the Mk-57’s 7.81 meters. The Type 055’s beam and draft is likely sufficient for all 112 VLS to accommodate the largest 9 meter variant.

What this means in practice, is that an individual Chinese universal VLS cell can accommodate larger missiles than other international equivalents. In the case of Type 055, its 112 VLS count is lower than the Ticonderoga-class’ 122 or Sejong-class’ 128, but each cell has a larger internal volume, with the potential to carry a larger missile.

The Type 055’s VLS will likely field existing weapons that have been integrated into the Type 052D, such as the YJ-18 anti ship missile, and current variants of HHQ-9 naval SAMs (thought to be the B variant). But the nature of the universal VLS, means any future payloads could be potentially integrated into the system, such as future SAMs, AShMs, LACMs, ASROCs or even ballistic missile defense payloads.

Aside from VLS, the H/PJ-38 130mm main gun is the same type which equips the Type 052D, but curiously lacks a muzzle brake as opposed to the Type 052D. The aforementioned H/PJ-11 and HHQ-10 CIWS and decoy launchers provide last ditch air defense, and panels on the sides of the amidships region likely hide standard triple 324mm torpedo tubes for short range last ditch ASW.

Future Type 055 variants may alter the VLS count and adopt more exotic armament such as rail guns or directed energy weapons.

Sensors

The Type 055’s integrated mast is suspected to likely mount a type of X band active phased array radar in four fixed panels.

The Type 055 is equipped with a further evolution of the Type 346 active phased array radar, dubbed Type 346B. The original Type 346 was a dual band radar in the S and C bands, however it is unknown if the Type 055 retains the C band radar given the likely presence of an X band radar. There are some suggestions Type 346B may use Gallium Nitride technology, which would likely be within China’s current industrial capabilities.

Some publications have mentioned the low placement of the 055’s main Type 346B arrays as a limitation or flaw in its design, which warrants some consideration. Warships such as the Royal Navy’s Type 45 and Indian Kolkata-class mount S band arrays atop a high mast, to provide greater radar horizon detection range against low flying targets. However, mounting arrays in a higher position also limits the size of the array, meaning the absolute power of the radar system is also reduced.

The Type 055, Type 052C/D, and Burke class adopt a “lower mounted” configuration. Some ships such as the Japanese Kongo/Atago-class, and the Spanish F100 and Australian Hobart-classes mount their main radar arrays at a slightly higher level than Burkes, Type 052C/D or Type 055 but lower than Type 45 or Indian Kolkata-class destroyers.

For the Type 055, the limitations of mounting their Type 346B at the level of the main deckhouse does not inherently compromise the ship’s overall radar horizon range, as the integrated mast above the deckhouse will likely mount the aforementioned X band radar. X band radars are better suited for horizon search and discrimination of low flying targets compared to S band radars, and having a dedicated high mounted X band radar allows the benefits of a larger and more powerful S band radar in the form of the Type 346B. Overall, the radar configuration of any warship is a compromise between various competing requirements, and each configuration has different advantages and disadvantages.

Outside of radars, other arrays and mounts for ESM, ECM and EO sensors and datalinks have also been identified around the ship, but the designation of these systems are not known. Based on the external mounts that can be identified they are likely a newer generation than what was present on existing ships like Type 052D.

In terms of subsurface sensors, an opening in the Type 055’s similar to that of Type 052D and Type 054A suggests it contains a variable depth sonar, with a linear towed array sonar expected as well. Images during the launch of the first Type 055 also demonstrate a large bulbous bow indicate of a large bow sonar, significantly greater than what existing Chinese surface combatants have been equipped with.

Powerplant

The Type 055 does not field an integrated electric propulsion system.

For propulsion, the Type 055 is equipped with four QC-280 gas turbines, each rated at 28 MW, in a COGAG arrangement. For generating electricity, a brief view of a CAD image in 2017 indicated it is equipped with two pairs of three generators, likely small gas turbines, for a total of six generators. It has been suggested that these gas turbines may be QD50s rated at 5 MW, which would provide a total of 30 MW to the ship. By comparison, the Flight III Burke is equipped with three 4MW gas turbine generators for a total of 12 MW.

The greater power generating capacity is likely to supply the variety of new generation sensors aboard the ship, which are likely to consume substantial amounts of power. Future variants of 055 are expected to field IEPS, which would enable the ship to field even more powerful sensors and weapons such as rail guns and DEWs.

https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/all-you-need-to-know-about-chinas-new-stealth-destroyer/

The Type 055 adopts a conventional flared hull with distinctive stealthy features including an enclosed bow, where mooring points, anchor chains and other equipment are hidden belowdecks. The bow armament adopts a similar configuration to the 052C/D, with the main gun located most anterior, followed by a 64 cell block of VLS, and the eleven barrel H/PJ-11 30mm close in weapons system (CIWS).

The main deckhouse is similar to the proven configuration that the preceding 052D adopts, with fixed four face phased array radars (PARs) arranged for overlapping 360 degree coverage. However, the mast atop the deckhouse is a more advanced integrated mast, with sensors and datalinks integrated into a single structure.

Similarly, the amidships area and the smoke stack is a continuous single structure extending from the main deckhouse. A continuous integrated structure not only provides additional volume for various uses (such as amidships RHIB davits), but also reduces deck clutter and the ship’s associated radar cross section. The single integrated smoke stack is notable, as it appears to shield the exhausts from the ship’s gas turbines to a greater degree, likely to reduce infrared signatures and radar cross section.

Moving posteriorly, there is a 48 cell block of VLS, leading to the aft helicopter hangar structure featuring two helicopter hangars. A step structure atop this hangar was once suspected to possibly accommodate a volume search radar, but instead will likely be equipped with a small dome or other electronics. A 24 cell HHQ-10 missile CIWS and four decoy turrets are equipped atop the hangar. A large stern helipad, greater in size than that on the 052C/D destroyers, accommodates the ship’s organic helicopter complement.

There have been some reports that the Type 055 may involve aluminium in its construction, however at this stage there are no credible indicators for this suggestion.

Armament

The bulk of the Type 055’s firepower – as in all modern surface combatants – resides in its missile armament that can be judged in its VLS.

The Type 055 uses the same universal VLS on the Type 052D, but with a larger total cell count of 112. As written elsewhere, the Chinese Navy’s universal VLS can fire missiles in a cold launch method, or a hot launch using concentric canister launch. Each individual square VLS cell has a diameter of 0.85 meters, significantly greater than that of the Mk-41 VLS at 0.635 meters or even the Zumwalt class’ Mk-57 PVLS at 0.71 meters. The universal VLS comes in three lengths, the greatest being 9 meters, which is longer than the Mk-41’s largest strike length variant at 7.7 meters or the Mk-57’s 7.81 meters. The Type 055’s beam and draft is likely sufficient for all 112 VLS to accommodate the largest 9 meter variant.

What this means in practice, is that an individual Chinese universal VLS cell can accommodate larger missiles than other international equivalents. In the case of Type 055, its 112 VLS count is lower than the Ticonderoga-class’ 122 or Sejong-class’ 128, but each cell has a larger internal volume, with the potential to carry a larger missile.

The Type 055’s VLS will likely field existing weapons that have been integrated into the Type 052D, such as the YJ-18 anti ship missile, and current variants of HHQ-9 naval SAMs (thought to be the B variant). But the nature of the universal VLS, means any future payloads could be potentially integrated into the system, such as future SAMs, AShMs, LACMs, ASROCs or even ballistic missile defense payloads.

Aside from VLS, the H/PJ-38 130mm main gun is the same type which equips the Type 052D, but curiously lacks a muzzle brake as opposed to the Type 052D. The aforementioned H/PJ-11 and HHQ-10 CIWS and decoy launchers provide last ditch air defense, and panels on the sides of the amidships region likely hide standard triple 324mm torpedo tubes for short range last ditch ASW.

Future Type 055 variants may alter the VLS count and adopt more exotic armament such as rail guns or directed energy weapons.

Sensors

The Type 055’s integrated mast is suspected to likely mount a type of X band active phased array radar in four fixed panels.

The Type 055 is equipped with a further evolution of the Type 346 active phased array radar, dubbed Type 346B. The original Type 346 was a dual band radar in the S and C bands, however it is unknown if the Type 055 retains the C band radar given the likely presence of an X band radar. There are some suggestions Type 346B may use Gallium Nitride technology, which would likely be within China’s current industrial capabilities.

Some publications have mentioned the low placement of the 055’s main Type 346B arrays as a limitation or flaw in its design, which warrants some consideration. Warships such as the Royal Navy’s Type 45 and Indian Kolkata-class mount S band arrays atop a high mast, to provide greater radar horizon detection range against low flying targets. However, mounting arrays in a higher position also limits the size of the array, meaning the absolute power of the radar system is also reduced.

The Type 055, Type 052C/D, and Burke class adopt a “lower mounted” configuration. Some ships such as the Japanese Kongo/Atago-class, and the Spanish F100 and Australian Hobart-classes mount their main radar arrays at a slightly higher level than Burkes, Type 052C/D or Type 055 but lower than Type 45 or Indian Kolkata-class destroyers.

For the Type 055, the limitations of mounting their Type 346B at the level of the main deckhouse does not inherently compromise the ship’s overall radar horizon range, as the integrated mast above the deckhouse will likely mount the aforementioned X band radar. X band radars are better suited for horizon search and discrimination of low flying targets compared to S band radars, and having a dedicated high mounted X band radar allows the benefits of a larger and more powerful S band radar in the form of the Type 346B. Overall, the radar configuration of any warship is a compromise between various competing requirements, and each configuration has different advantages and disadvantages.

Outside of radars, other arrays and mounts for ESM, ECM and EO sensors and datalinks have also been identified around the ship, but the designation of these systems are not known. Based on the external mounts that can be identified they are likely a newer generation than what was present on existing ships like Type 052D.

In terms of subsurface sensors, an opening in the Type 055’s similar to that of Type 052D and Type 054A suggests it contains a variable depth sonar, with a linear towed array sonar expected as well. Images during the launch of the first Type 055 also demonstrate a large bulbous bow indicate of a large bow sonar, significantly greater than what existing Chinese surface combatants have been equipped with.

Powerplant

The Type 055 does not field an integrated electric propulsion system.

For propulsion, the Type 055 is equipped with four QC-280 gas turbines, each rated at 28 MW, in a COGAG arrangement. For generating electricity, a brief view of a CAD image in 2017 indicated it is equipped with two pairs of three generators, likely small gas turbines, for a total of six generators. It has been suggested that these gas turbines may be QD50s rated at 5 MW, which would provide a total of 30 MW to the ship. By comparison, the Flight III Burke is equipped with three 4MW gas turbine generators for a total of 12 MW.

The greater power generating capacity is likely to supply the variety of new generation sensors aboard the ship, which are likely to consume substantial amounts of power. Future variants of 055 are expected to field IEPS, which would enable the ship to field even more powerful sensors and weapons such as rail guns and DEWs.

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2014

- Messages

- 32,663

- Likes

- 151,106

What “world class stealth”?Nice Ships, one thing i like About China is how you guys do things in time. T055 took just 3.5 years to complete from Drowing Board to sea launch with state of the Art Agies, uvls and world class Stealth while we are stuck with ugly, horrendous looking, under powered, unprotected, outdated, semi stealth at best kolkatas and Visakhapatnams for the future.

how many T-055 Ships is Chinese navy want to produce ?

When was the last time China went into a naval war?

Indian ships are designed as per Indian strategic requirements which are agreed and approved 10-15 years in advance. This does not mean Indian ships are any inferior to any other.

SexyChineseLady

New Member

- Joined

- Oct 3, 2016

- Messages

- 5,178

- Likes

- 4,008

India’s strategic requirements are very low. When was the last time you fought anyone outside South Asia? With due respect to the Pakistanis but South Asia is simply not a very competitive region.What “world class stealth”?

When was the last time China went into a naval war?

Indian ships are designed as per Indian strategic requirements which are agreed and approved 10-15 years in advance. This does not mean Indian ships are any inferior to any other.

China has to deal with the US, Russia, Australia, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Vietnam too and they’ve beaten the US. All of them are far more formidable people — economically, militarily and technologically — than Indians. India only has Pakistan.

- Joined

- Aug 14, 2015

- Messages

- 1,419

- Likes

- 2,819

Requirements are low? The requirement of dominating IOR is low? Maybe you will find it more understandable if I said that India's strategic ambitions are large.India’s strategic requirements are very low.

Thank god for small mercies.China has to deal with the US, Russia, Australia, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Vietnam too and they’ve beaten the US.

And not China? Yeah, right.India only has Pakistan.

Maybe he is talking about integrated masts? AFAIK, Project 18 Destroyers will have them. Meanwhile PLAN already has them on Type 055 destroyers.What “world class stealth”?

Aghore_King

New Member

- Joined

- May 8, 2017

- Messages

- 461

- Likes

- 1,122

And all of these countries have beaten the crap out of your people whenever you've fought with them , so fighting again is an unlikely scenario in future.India’s strategic requirements are very low. When was the last time you fought anyone outside South Asia? With due respect to the Pakistanis but South Asia is simply not a very competitive region.

China has to deal with the US, Russia, Australia, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Vietnam too and they’ve beaten the US. All of them are far more formidable people — economically, militarily and technologically — than Indians. India only has Pakistan.

SexyChineseLady

New Member

- Joined

- Oct 3, 2016

- Messages

- 5,178

- Likes

- 4,008

No, not China. There is very little modern Chinese assets along the Indian border compared the massive forces China has on its east coast facing the US, Japan, South Korea and Japan.And not China? Yeah, right.

The Chinese military are involved in constant intercepts and probes with the US, Japan, Taiwan, etc. in the east. There are many pictures of these engagements.

Japanese F-15 taken from Chinese TU-154:

J-11 from US P-8

H-6K and ROC F-CK1:

J-11 from another USN encounter:

US Navy photo released from an encounter in the South China Sea:

There are no photos of this kind with India.

China simply doesn’t operate a lot of assets near India. Our rivals are to our east. As far away from India as we could be.

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 6,510

- Likes

- 7,217

1 year is more than enough. They will use some sailors from type 52....How many years of training do the sailors go through to operate such ships. And how are they even drafted.

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 6,510

- Likes

- 7,217

2 versus 8.How is this comparable to Zumwalt class ?

______________________,,,,

Quantity matters also.

J20!

New Member

- Joined

- Oct 20, 2011

- Messages

- 2,748

- Likes

- 1,546

Clear pics of the Type 055 destroyer's mid section and the sensor arrays aft of her deck-house/superstructure:

The decoy launchers on her hanger are quite stealthy compared to the units used on the Type 052D; and of-course there are a lot more launch tubes on them. 24+32 tubes on each side. Are they both decoy launchers?

The decoy launchers on her hanger are quite stealthy compared to the units used on the Type 052D; and of-course there are a lot more launch tubes on them. 24+32 tubes on each side. Are they both decoy launchers?

Last edited:

- Joined

- Dec 17, 2009

- Messages

- 13,811

- Likes

- 6,734

It is nice to see China coming out of 1926 Yagi antennas. If I saw one more of those I was going to laugh.Captured on amateur video heading out or returning from her first sea trial:

su30mki2017

New Member

- Joined

- Aug 23, 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Likes

- 151

2 versus 8.

Quantity matters also.

How is this comparable to Zumwalt class ?

______________________,,,,

The Maoists didn't get their hands on (comrade) chi mak's espionage cd,

So they copied Russian & Ukrainian (soviet) technology to build blue water navy and not based on American technology because (TONGZHI) chi mak went to prison.

otherwise they could have built DDX (zumwalt destroyer) clone but

sum ting wong happened.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chi_Mak

SEE THE FULL VIDEO BELOW

The Maoist must have said ho lee fuk to their handlers , when their fellow long time sleeper agents got arrested before boarding flight to middle kingdom

Last edited:

Articles

-

India Strikes Back: Operation Snow Leopard - Part 1

- mist_consecutive

- Replies: 9

-

Aftermath Galwan : Who holds the fort ?

- mist_consecutive

- Replies: 33

-

The Terrible Cost of Presidential Racism(Nixon & Kissinger towards India).

- ezsasa

- Replies: 40

-

Modern BVR Air Combat - Part 2

- mist_consecutive

- Replies: 22

-

Civil & Military Bureaucracy and related discussions

- daya

- Replies: 32