In the Indian media and on social sites of the Internet there exist certain views about Chinese infrastructure and roads bordering India, some of which would be alarming to any Indian. These impressions about Chinese preparations on India's borders get repeated every time there is a new crisis at the border, such as the stand off in Ladakh after a Chinese incursion in early 2013. Among commonly held views are the idea that the Chinese have built all weather roads all along the border with India. These roads it is said, will allow the Chinese to rapidly move in forces to the border and into India if necessary. A contrasting lack of infrastructure on the Indian side is usually referred to simultaneously, while fears are expressed that India is likely to suffer another humiliating and even more disastrous defeat in any future conflict with China. Most articles refer to Indian infrastructure with some degree of first hand knowledge from people who have been to border areas and recall the lack of roads leading to the Chinese border.

However, very little attention is paid in the Indian lay media and internet sites to what the Chinese have actually built across the border – a surprising omission considering that one meter resolution satellite inages are freely available to anyone with a computer and internet access in the form of Google Earth, with images that are often less then year old and rarely over ten years old. It is not just the military and intelligence agencies that have access to such images – any concerned citizen can study them. That is exactly what has been done here and will be detailed below. The idea of this study was to locate and follow every single road in Aksai Chin in north west India in satellite images to see the level of preparedness and potential capability of the Chinese in this region. Note that this study does not extend beyond the Aksai Chin region on the northwest of Jammu and Kashmir, and has no information on Chinese infrastructure and border roads in the east, bordering the eastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

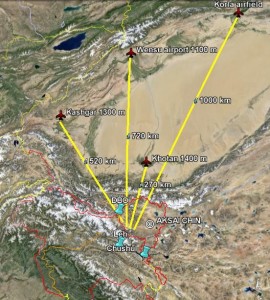

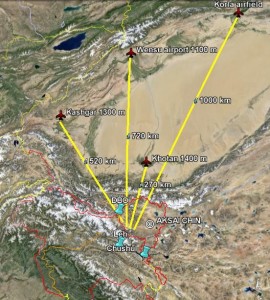

A good place to start would be to address the frequently stated idea that the Chinese have built first class all weather motorable roads all along the border with India. This is decidedly untrue in Aksai Chin. For a Line of Actual Control (LAC) that is over 300 km long in the Ladakh/Aksai Chin region, the Chinese only have roads that extend about 10 to 20 km at the LAC. This is in stark contrast to the belief that every inch of the border with India has motorable roads. However this small length of roads at the frontier with India is not due to Chinese negligence. It is physically not possible to build roads all along the border at the LAC. The rest of the frontier consists of mountains that are frequently over 6 km (20,000 feet) high, or in some areas, water bodies. The Chinese have built approach roads to all the areas that they can approach at the border. The actual length of those areas is quite small compared to the total length of the LAC (Image 1).

The thick blue line is the G 219 highway and the green roads are branches. Branches numbered 3 to 8 reach the LAC. Note the absence of any Chinese roads at the LAC (red line) for a long stretch between DBO in the north and opposite Leh in the south.

Towards the Chinese occupied (eastern) side of the LAC – the Chinese seem to enjoy a degree of geographical advantage. They have already occupied Tibet which is a 5 km high plateau. Aksai Chin is a geographical continuation of the Tibet plateau that the Chinese, under Mao roughly invaded and occupied in 1950. It is easier to build roads along flat plains than in mountains and the Chinese simply built roads from Tibet right through Aksai Chin in 1957, an act that went uncontested by an India under Jawaharlal Nehru's leadership. After the 1962 conflict, Indian positions were pushed back to the current LAC.

The Aksai Chin plateau goes all the way to the LAC and somewhat beyond it in some areas – such as the Depsang plain area near the Indian post of Daulat Beg Oldi. But near the LAC the plateau of Aksai Chin rises up into mountains – sometimes 6 km high and then rapidly descends into deep Himalayan river valleys on the Indian side. One such valley is the Shyok river valley in Ladakh. The Shyok river valley is about 1000 meters or more lower than the Chinese positions on the Aksai Chin plateau. In some areas Indian positions are physically close to the LAC, but a 1000 or 1500 meter high wall of mountain has to be climbed in a five to ten km distance to reach the actual LAC. In contrast to this, on the Chinese occupied side the terrain is relatively flat – and remains at 4800 to 5,300 meters.

This terrain offers India some advantages and disadvantages and it offers the Chinese some advantages and disadvantages. The Chinese are operating on relatively flat terrain where road building is easier, and they can approach the LAC through a few river valley gaps in the mountains. But all the Chinese positions remain above 5000 meters in altitude and there is no relief, no way of getting to lower altitudes for hundreds of kilometers on the Chinese side. Human life is difficult and hazardous at altitudes as high as 5000 meters and life threatening altitude sickness is an ever present possibility even for acclimatized troops, requiring quick evacuation to lower altitudes. The intense cold can cause frostbite and gangrene of the fingers and toes. Water boils at a low 80 degrees Centigrade making cooking slow and difficult. Even flames burn at lower temperatures and fuel and food need to be transported hundreds of kilometers.

While conditions on the Indian side of the LAC are similar, there are again some advantages and disadvantages. Lower altitude regions are much closer on the Indian side, ranging from a few dozen to tens of kilometers. But steep mountains make road construction towards the LAC difficult and fraught with the risk of avalanches. The Himalayas are “young mountains” and consist of loose rock rather than hard compact rock and this increases the risk of avalanches. Mountain roads necessarily have to be cut into the sides of mountains in a zig-zag pattern so that the incline is not too steep for laden vehicles to climb, so a straight line distance of just 10 kilometers may become 30 or 40 kilometers by road. This makes logistics by air transport very valuable on the Indian side. What this means for India is that Indian positions can be defended only if air transport is kept up and local air dominance is maintained in times of crisis.

The roads on the Chinese side are not totally free from the issues faced on the Indian side. The main Chinese highway from Xinjiang to Tibet, the G 219 passes through Aksai Chin and is mostly an all weather motor-able road. But this road is, on average, more than 100 kilometers from the LAC. In order to approach the LAC from the G 219, the Chinese have constructed six finger like roads that radiate through Aksai Chin like fingers from the main highway towards the LAC (Image 1).

Although the terrain is relatively flat on the Chinese occupied side it is not totally flat. While the average altitude remains around 5000 meters there are some mountains and rivers en route. Because of this the sinuous roads following river valleys from the highway to the LAC are between 120 and 170 km long. None of these roads appear to be all weather roads, with river crossings without bridges and “kutcha” surfaces over many lengths. Any Chinese military action in Aksai Chin will have Chinese logistics lines passing over these roads that are more than 120 km long and over 5 km high. In a conflict lasting more than a few weeks disruption of these long logistics lines would impair Chinese ability to conduct operations at the LAC. The terrain in Aksai Chin is flat and there is nowhere to hide so movement on the roads to the LAC should be visible to satellite reconnaissance for weeks in advance.

However all this does not mean that the Chinese are unprepared or have a weak presence at the LAC. The six fair weather tracks/roads from the G 219 lead to at least eight points where the Chinese have built roads right up to the LAC (Image 1). In general the Chinese have made patrolling at the LAC easier for themselves by having good quality roads at the LAC, even if the feeder roads to the area are not of such high quality. These border roads sometimes run parallel to the LAC for a few km, or simply end abruptly at the LAC. In every case the Chinese characteristically end their road with a loop so that a patrolling vehicle can go round the loop and reverse its direction back towards Chinese controlled areas (Image 2).

The image below shows the characteristic loop that many Chinese LAC roads end with making it easy for patrolling vehicles to reverse direction

It appears that the Chinese have deliberately made it convenient to patrol using vehicles. This could be an advantage in terms of covering longer distances and putting less strain on humans living and working above 5000 meters in altitude. On the other hand a fast drive by in a vehicle leaves less time for close observation, and could serve as an opportunity for an infiltrating force to hide unobserved.

There are two areas at the LAC, one in the north and one in the south, where the Chinese roads and positions come right up to the Indian controlled side. These two areas are separated by a 100 km gap of high mountains where the Chinese do not appear to have any infrastructure up to the LAC.

In the north, very close to Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) where the recent standoff between Indian and Chinese forces took place, the Chinese have build roads running parallel to the LAC for a few km. The approach road here has been built along the banks of a river called the Kizil Jilga which extends from the LAC right into Chinese held Aksai Chin. There are multiple Chinese military establishments along this road and on side roads, including some large buildings that could house hundreds of men. It is known that the Chinese have built oxygen enriched accommodation for the comfort of their men working in high altitude regions. However this feature, if true, can only delay the acclimatization that is required for living in this area. This area also has at least one side road which leads to a mountainside tunnel entrance (Image 3). The Chinese are known to house missiles and military equipment in mountain tunnels, but the purpose of this tunnel is unclear. There are several bridges across the river in the Chinese positions leading to DBO – all of which would be valid targets in war, either to hinder supplies to the Chinese forces, or to hinder movement of an invading Indian force.

Mountainside tunnel entrance in north-east Aksai Chin

As mentioned earlier, to the south of these Chinese positions near DBO, the LAC has no sign of any Chinese roads or infrastructure for a distance of about 100 km. This is a mountainous region with 6000 meter high mountains and on the Indian side is a deep valley – the Shyok river valley. These features make a formal invasion unlikely from either side, although infiltration of small groups could always be a possibility. There appears no easy way of bringing in heavy war fighting equipment in this 100 km mountainous wall south of DBO.

Further south of the wall of mountains, the heights become less formidable and once again Chinese and Indian positions come into contact. Over a distance of 60 km of the LAC in this southern part of Aksai Chin the Chinese have built roads extending like spidery fingers up to the LAC in no less than 6 points. Each of these roads is separated from the next by a distance of 5 to 30 km. In the northern half of this area are four roads like prongs of a fork ending at the LAC. These roads connect up with each other and the G 219, although the condition of the roads is far from being “all weather” roads. These roads have many Chinese military installations, with numerous patrolling vehicles, accommodation, and what appears to be an underground complex along with a structure that could be a reinforced concrete bomb-proof shelter. At one point the Chinese positions overlook Indian positions on the northern tip of the Pangong lake. Overall, the connectivity of this area with other areas and the G 219 highway does not appear very good, with streams crossing over the roads in many areas (Image 4) and the actual road distance from the all weather G 219 being over 150 km.

One of the roads leading to the LAC obliterated by river water flow

Going southwards, near the Indian position of Chushul, where great battles were fought in 1962, the Chinese have roads up to the LAC on the north and south side of two lakes – the Pangong and Spangur lakes. These roads appear to have many Chinese military installations – including what appear to be barracks for residential accommodation. Very close to Chushul, on the south bank of Spangur lake is a Chinese base with a huge model Chinese flag created on the ground to be visible to satellites – signaling Chinese presence here (Image 5). Similarly in another base situated on the north bank of the Pangong lake about 35 km to the north there is a huge sign showing a map of China and some Chinese lettering and an image of a face and people reminiscent of Mao era propaganda images, all visible to aerial or satellite photography. The Chinese seem particularly keen to publicly display their presence in this area. The area also has a visible communication center with communication tower and satellite antennae.

Giant Chinese flag visible from the air in base south of Spangur lake near Chushul

The four nearest airfields from which the Chinese can expect air support in case of conflict are in Xinjiang. Only one, in Khotan is about 270 km away. The others are 500, 700 or 1000 km away (Image 6). Given air to air refueling these distances are not insurmountable. Aircraft could fly in low using the mountains to give them radar cover before appearing over Aksai Chin, but the airfields themselves would be prime Indian targets in a conflict and taking out the two closer ones would severely hamper Chinese air operations. Two high altitude Tibet airfields near Lhasa and Xigaze (known to have Sukhoi Su 27 aircraft) are over 1000 km away. However any fixed wing aircraft or either side will have to stay at fairly high altitudes above Aksai Chin to avoid ground based air defences. That would expose them to the radar coverage of AWACS aircraft. In addition the rarefied atmosphere would change the ballistics of free fall bombs, rockets and even cannon fire. Apart from that, diving attack profiles requiring pulling up of aircraft from from an altitude close to the ground would require extra care as the ability to pull up and maneuver would be impaired at the altitudes above Aksai Chin.

Given the geographical realities described above and the visible Chinese infrastructure in Aksai Chin it is possible to speculate on what the Chinese might be able to do and what India could do in the region.

Could the Chinese mount an offensive against Indian positions in the region? This question can be answered by asking “What sort of offensive?” Most Indian positions are in the valleys a thousand meters or more below the Chinese positions and in order to enter these areas the Chinese will have to descend down steep mountain slopes over roads that will not allow heavy armour. So a heavy armour invasion coming down from the mountains is unlikely. In any case the Chinese do not appear to have housed heavy armour in Aksai Chin. In the absence of a heavy mechanized offensive the Chinese will have to send masses of troops downhill. For this they would have to build up more troops and supplies in Aksai Chin for they do not currently appear to have a ready invasion force sitting in Aksai Chin. Such a build up would take time and provide some advance notice to India because the movement of supplies into Aksai Chin can be monitored via satellite imagery, Humint and Elint.

Airfields in Xinjiang, marked with names, elevation above sea level and yellow lines indicating distance from LAC

Having said that, there are a few areas where Chinese and Indian positions exist at the same high altitude, virtually face to face. Instead of an offensive that goes down into the valleys, the Chinese could simply opt to evict all Indian positions from the heights and occupy the heights for themselves. India would have to resist this by any means. Air power would play a big role. The flat terrain in Aksai Chin does allow the use of light armoured vehicles and artillery and an Indian capability to transport such equipment by air to those areas would be desirable. Armed and transport helicopters with an ability to function usefully at heights up to 5,500 meters would be useful. Air dominance and robust logistics via air transport is likely to play a key role for India, given that all supplies have to be carried up to the heights to supply Indian positions there.

As regards a possible Indian invasion into Aksai Chin, it would not be right to view Aksai Chin in isolation. Aksai Chin is a harsh plateau and while it would be technically possible for India to recapture territory there, holding it in the long term would have to pay for itself in the advantages gained, given that all supplies and men would have to be transported uphill and then scores or hundreds of kilometers on the plateau itself.

However if China were to start a misadventure in Arunachal Pradesh, it would be prudent to grab chunks of Aksai Chin and cut off the G 219 Tibet-Xinjiang highway as well as the supply lines to Chinese forces near the LAC. A brief review of the satellite images of the G 219 highway in Aksai Chin reveals 40 to 50 heavy vehicles on the highway at the time of taking of the images. The highway itself is around 200 km long in Aksai Chin and assuming a 4 hour journey and a 20 ton load per truck, peacetime transport via the highway between Tibet and Xinjiang appears to be at least 5000 tons per day. This could be increased greatly in times of crisis and this highway would need to be cut off. The terrain of Aksai Chin seems to offer many ways of cutting or disrupting the highway, either by air attack or special forces that are airdropped into the region. Local air dominance over Aksai Chin would be critical in this regard. One curious feature is the absence of evidence of boating activity on the numerous lakes in Aksai Chin. Of interest here is the Pangong lake whose western end is in Indian controlled territory but its eastern end is close to the G 219. This water body may be a candidate for naval special forces action.

No matter which way the Chinese positions and infrastructure is viewed, it is an unavoidable fact that powerful airlift capability backed by air dominance and an ability to conduct precision air strikes at high altitude are vitally necessary for India should conflict recur in the region.

The MMRCA deal, the induction of light and heavy lift helicopters, combat helicopters, transport aircraft and artillery would require far more priority and urgency than is being shown by the somnolent sloth of Indian bureaucracy and delays caused by political bickering and backstabbing, It is to be hoped that the civilian Indian leadership are able to display some evidence of being aware of the realities of threats that exist at the border and the responses required. A laudable desire for peace needs to be backed up by the ability to win wars and this requires the Indian government to display far more urgent peacetime preparation than is visible to the Indian public.

However, very little attention is paid in the Indian lay media and internet sites to what the Chinese have actually built across the border – a surprising omission considering that one meter resolution satellite inages are freely available to anyone with a computer and internet access in the form of Google Earth, with images that are often less then year old and rarely over ten years old. It is not just the military and intelligence agencies that have access to such images – any concerned citizen can study them. That is exactly what has been done here and will be detailed below. The idea of this study was to locate and follow every single road in Aksai Chin in north west India in satellite images to see the level of preparedness and potential capability of the Chinese in this region. Note that this study does not extend beyond the Aksai Chin region on the northwest of Jammu and Kashmir, and has no information on Chinese infrastructure and border roads in the east, bordering the eastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

A good place to start would be to address the frequently stated idea that the Chinese have built first class all weather motorable roads all along the border with India. This is decidedly untrue in Aksai Chin. For a Line of Actual Control (LAC) that is over 300 km long in the Ladakh/Aksai Chin region, the Chinese only have roads that extend about 10 to 20 km at the LAC. This is in stark contrast to the belief that every inch of the border with India has motorable roads. However this small length of roads at the frontier with India is not due to Chinese negligence. It is physically not possible to build roads all along the border at the LAC. The rest of the frontier consists of mountains that are frequently over 6 km (20,000 feet) high, or in some areas, water bodies. The Chinese have built approach roads to all the areas that they can approach at the border. The actual length of those areas is quite small compared to the total length of the LAC (Image 1).

The thick blue line is the G 219 highway and the green roads are branches. Branches numbered 3 to 8 reach the LAC. Note the absence of any Chinese roads at the LAC (red line) for a long stretch between DBO in the north and opposite Leh in the south.

Towards the Chinese occupied (eastern) side of the LAC – the Chinese seem to enjoy a degree of geographical advantage. They have already occupied Tibet which is a 5 km high plateau. Aksai Chin is a geographical continuation of the Tibet plateau that the Chinese, under Mao roughly invaded and occupied in 1950. It is easier to build roads along flat plains than in mountains and the Chinese simply built roads from Tibet right through Aksai Chin in 1957, an act that went uncontested by an India under Jawaharlal Nehru's leadership. After the 1962 conflict, Indian positions were pushed back to the current LAC.

The Aksai Chin plateau goes all the way to the LAC and somewhat beyond it in some areas – such as the Depsang plain area near the Indian post of Daulat Beg Oldi. But near the LAC the plateau of Aksai Chin rises up into mountains – sometimes 6 km high and then rapidly descends into deep Himalayan river valleys on the Indian side. One such valley is the Shyok river valley in Ladakh. The Shyok river valley is about 1000 meters or more lower than the Chinese positions on the Aksai Chin plateau. In some areas Indian positions are physically close to the LAC, but a 1000 or 1500 meter high wall of mountain has to be climbed in a five to ten km distance to reach the actual LAC. In contrast to this, on the Chinese occupied side the terrain is relatively flat – and remains at 4800 to 5,300 meters.

This terrain offers India some advantages and disadvantages and it offers the Chinese some advantages and disadvantages. The Chinese are operating on relatively flat terrain where road building is easier, and they can approach the LAC through a few river valley gaps in the mountains. But all the Chinese positions remain above 5000 meters in altitude and there is no relief, no way of getting to lower altitudes for hundreds of kilometers on the Chinese side. Human life is difficult and hazardous at altitudes as high as 5000 meters and life threatening altitude sickness is an ever present possibility even for acclimatized troops, requiring quick evacuation to lower altitudes. The intense cold can cause frostbite and gangrene of the fingers and toes. Water boils at a low 80 degrees Centigrade making cooking slow and difficult. Even flames burn at lower temperatures and fuel and food need to be transported hundreds of kilometers.

While conditions on the Indian side of the LAC are similar, there are again some advantages and disadvantages. Lower altitude regions are much closer on the Indian side, ranging from a few dozen to tens of kilometers. But steep mountains make road construction towards the LAC difficult and fraught with the risk of avalanches. The Himalayas are “young mountains” and consist of loose rock rather than hard compact rock and this increases the risk of avalanches. Mountain roads necessarily have to be cut into the sides of mountains in a zig-zag pattern so that the incline is not too steep for laden vehicles to climb, so a straight line distance of just 10 kilometers may become 30 or 40 kilometers by road. This makes logistics by air transport very valuable on the Indian side. What this means for India is that Indian positions can be defended only if air transport is kept up and local air dominance is maintained in times of crisis.

The roads on the Chinese side are not totally free from the issues faced on the Indian side. The main Chinese highway from Xinjiang to Tibet, the G 219 passes through Aksai Chin and is mostly an all weather motor-able road. But this road is, on average, more than 100 kilometers from the LAC. In order to approach the LAC from the G 219, the Chinese have constructed six finger like roads that radiate through Aksai Chin like fingers from the main highway towards the LAC (Image 1).

Although the terrain is relatively flat on the Chinese occupied side it is not totally flat. While the average altitude remains around 5000 meters there are some mountains and rivers en route. Because of this the sinuous roads following river valleys from the highway to the LAC are between 120 and 170 km long. None of these roads appear to be all weather roads, with river crossings without bridges and “kutcha” surfaces over many lengths. Any Chinese military action in Aksai Chin will have Chinese logistics lines passing over these roads that are more than 120 km long and over 5 km high. In a conflict lasting more than a few weeks disruption of these long logistics lines would impair Chinese ability to conduct operations at the LAC. The terrain in Aksai Chin is flat and there is nowhere to hide so movement on the roads to the LAC should be visible to satellite reconnaissance for weeks in advance.

However all this does not mean that the Chinese are unprepared or have a weak presence at the LAC. The six fair weather tracks/roads from the G 219 lead to at least eight points where the Chinese have built roads right up to the LAC (Image 1). In general the Chinese have made patrolling at the LAC easier for themselves by having good quality roads at the LAC, even if the feeder roads to the area are not of such high quality. These border roads sometimes run parallel to the LAC for a few km, or simply end abruptly at the LAC. In every case the Chinese characteristically end their road with a loop so that a patrolling vehicle can go round the loop and reverse its direction back towards Chinese controlled areas (Image 2).

The image below shows the characteristic loop that many Chinese LAC roads end with making it easy for patrolling vehicles to reverse direction

It appears that the Chinese have deliberately made it convenient to patrol using vehicles. This could be an advantage in terms of covering longer distances and putting less strain on humans living and working above 5000 meters in altitude. On the other hand a fast drive by in a vehicle leaves less time for close observation, and could serve as an opportunity for an infiltrating force to hide unobserved.

There are two areas at the LAC, one in the north and one in the south, where the Chinese roads and positions come right up to the Indian controlled side. These two areas are separated by a 100 km gap of high mountains where the Chinese do not appear to have any infrastructure up to the LAC.

In the north, very close to Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) where the recent standoff between Indian and Chinese forces took place, the Chinese have build roads running parallel to the LAC for a few km. The approach road here has been built along the banks of a river called the Kizil Jilga which extends from the LAC right into Chinese held Aksai Chin. There are multiple Chinese military establishments along this road and on side roads, including some large buildings that could house hundreds of men. It is known that the Chinese have built oxygen enriched accommodation for the comfort of their men working in high altitude regions. However this feature, if true, can only delay the acclimatization that is required for living in this area. This area also has at least one side road which leads to a mountainside tunnel entrance (Image 3). The Chinese are known to house missiles and military equipment in mountain tunnels, but the purpose of this tunnel is unclear. There are several bridges across the river in the Chinese positions leading to DBO – all of which would be valid targets in war, either to hinder supplies to the Chinese forces, or to hinder movement of an invading Indian force.

Mountainside tunnel entrance in north-east Aksai Chin

As mentioned earlier, to the south of these Chinese positions near DBO, the LAC has no sign of any Chinese roads or infrastructure for a distance of about 100 km. This is a mountainous region with 6000 meter high mountains and on the Indian side is a deep valley – the Shyok river valley. These features make a formal invasion unlikely from either side, although infiltration of small groups could always be a possibility. There appears no easy way of bringing in heavy war fighting equipment in this 100 km mountainous wall south of DBO.

Further south of the wall of mountains, the heights become less formidable and once again Chinese and Indian positions come into contact. Over a distance of 60 km of the LAC in this southern part of Aksai Chin the Chinese have built roads extending like spidery fingers up to the LAC in no less than 6 points. Each of these roads is separated from the next by a distance of 5 to 30 km. In the northern half of this area are four roads like prongs of a fork ending at the LAC. These roads connect up with each other and the G 219, although the condition of the roads is far from being “all weather” roads. These roads have many Chinese military installations, with numerous patrolling vehicles, accommodation, and what appears to be an underground complex along with a structure that could be a reinforced concrete bomb-proof shelter. At one point the Chinese positions overlook Indian positions on the northern tip of the Pangong lake. Overall, the connectivity of this area with other areas and the G 219 highway does not appear very good, with streams crossing over the roads in many areas (Image 4) and the actual road distance from the all weather G 219 being over 150 km.

One of the roads leading to the LAC obliterated by river water flow

Going southwards, near the Indian position of Chushul, where great battles were fought in 1962, the Chinese have roads up to the LAC on the north and south side of two lakes – the Pangong and Spangur lakes. These roads appear to have many Chinese military installations – including what appear to be barracks for residential accommodation. Very close to Chushul, on the south bank of Spangur lake is a Chinese base with a huge model Chinese flag created on the ground to be visible to satellites – signaling Chinese presence here (Image 5). Similarly in another base situated on the north bank of the Pangong lake about 35 km to the north there is a huge sign showing a map of China and some Chinese lettering and an image of a face and people reminiscent of Mao era propaganda images, all visible to aerial or satellite photography. The Chinese seem particularly keen to publicly display their presence in this area. The area also has a visible communication center with communication tower and satellite antennae.

Giant Chinese flag visible from the air in base south of Spangur lake near Chushul

The four nearest airfields from which the Chinese can expect air support in case of conflict are in Xinjiang. Only one, in Khotan is about 270 km away. The others are 500, 700 or 1000 km away (Image 6). Given air to air refueling these distances are not insurmountable. Aircraft could fly in low using the mountains to give them radar cover before appearing over Aksai Chin, but the airfields themselves would be prime Indian targets in a conflict and taking out the two closer ones would severely hamper Chinese air operations. Two high altitude Tibet airfields near Lhasa and Xigaze (known to have Sukhoi Su 27 aircraft) are over 1000 km away. However any fixed wing aircraft or either side will have to stay at fairly high altitudes above Aksai Chin to avoid ground based air defences. That would expose them to the radar coverage of AWACS aircraft. In addition the rarefied atmosphere would change the ballistics of free fall bombs, rockets and even cannon fire. Apart from that, diving attack profiles requiring pulling up of aircraft from from an altitude close to the ground would require extra care as the ability to pull up and maneuver would be impaired at the altitudes above Aksai Chin.

Given the geographical realities described above and the visible Chinese infrastructure in Aksai Chin it is possible to speculate on what the Chinese might be able to do and what India could do in the region.

Could the Chinese mount an offensive against Indian positions in the region? This question can be answered by asking “What sort of offensive?” Most Indian positions are in the valleys a thousand meters or more below the Chinese positions and in order to enter these areas the Chinese will have to descend down steep mountain slopes over roads that will not allow heavy armour. So a heavy armour invasion coming down from the mountains is unlikely. In any case the Chinese do not appear to have housed heavy armour in Aksai Chin. In the absence of a heavy mechanized offensive the Chinese will have to send masses of troops downhill. For this they would have to build up more troops and supplies in Aksai Chin for they do not currently appear to have a ready invasion force sitting in Aksai Chin. Such a build up would take time and provide some advance notice to India because the movement of supplies into Aksai Chin can be monitored via satellite imagery, Humint and Elint.

Airfields in Xinjiang, marked with names, elevation above sea level and yellow lines indicating distance from LAC

Having said that, there are a few areas where Chinese and Indian positions exist at the same high altitude, virtually face to face. Instead of an offensive that goes down into the valleys, the Chinese could simply opt to evict all Indian positions from the heights and occupy the heights for themselves. India would have to resist this by any means. Air power would play a big role. The flat terrain in Aksai Chin does allow the use of light armoured vehicles and artillery and an Indian capability to transport such equipment by air to those areas would be desirable. Armed and transport helicopters with an ability to function usefully at heights up to 5,500 meters would be useful. Air dominance and robust logistics via air transport is likely to play a key role for India, given that all supplies have to be carried up to the heights to supply Indian positions there.

As regards a possible Indian invasion into Aksai Chin, it would not be right to view Aksai Chin in isolation. Aksai Chin is a harsh plateau and while it would be technically possible for India to recapture territory there, holding it in the long term would have to pay for itself in the advantages gained, given that all supplies and men would have to be transported uphill and then scores or hundreds of kilometers on the plateau itself.

However if China were to start a misadventure in Arunachal Pradesh, it would be prudent to grab chunks of Aksai Chin and cut off the G 219 Tibet-Xinjiang highway as well as the supply lines to Chinese forces near the LAC. A brief review of the satellite images of the G 219 highway in Aksai Chin reveals 40 to 50 heavy vehicles on the highway at the time of taking of the images. The highway itself is around 200 km long in Aksai Chin and assuming a 4 hour journey and a 20 ton load per truck, peacetime transport via the highway between Tibet and Xinjiang appears to be at least 5000 tons per day. This could be increased greatly in times of crisis and this highway would need to be cut off. The terrain of Aksai Chin seems to offer many ways of cutting or disrupting the highway, either by air attack or special forces that are airdropped into the region. Local air dominance over Aksai Chin would be critical in this regard. One curious feature is the absence of evidence of boating activity on the numerous lakes in Aksai Chin. Of interest here is the Pangong lake whose western end is in Indian controlled territory but its eastern end is close to the G 219. This water body may be a candidate for naval special forces action.

No matter which way the Chinese positions and infrastructure is viewed, it is an unavoidable fact that powerful airlift capability backed by air dominance and an ability to conduct precision air strikes at high altitude are vitally necessary for India should conflict recur in the region.

The MMRCA deal, the induction of light and heavy lift helicopters, combat helicopters, transport aircraft and artillery would require far more priority and urgency than is being shown by the somnolent sloth of Indian bureaucracy and delays caused by political bickering and backstabbing, It is to be hoped that the civilian Indian leadership are able to display some evidence of being aware of the realities of threats that exist at the border and the responses required. A laudable desire for peace needs to be backed up by the ability to win wars and this requires the Indian government to display far more urgent peacetime preparation than is visible to the Indian public.