Gessler

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 10, 2016

- Messages

- 2,308

- Likes

- 11,206

As a continuation/Part-2 of "A Brief History of Indian Orbital Rockets" (https://defenceforumindia.com/threads/a-brief-history-of-indian-orbital-rockets.82897/), this part covers those programs that are still to come.

NOTE: As with the preceding article, I will only be mentioning those programs that aim to develop a full-fledged orbital launch capability as their primary goal; as such programs like the Nano Satellite Launch Vehicle (NSLV) which in the opinion of this author are primarily aimed at a Sub-orbital launch capability, have been excluded.

Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV)

2021-2022

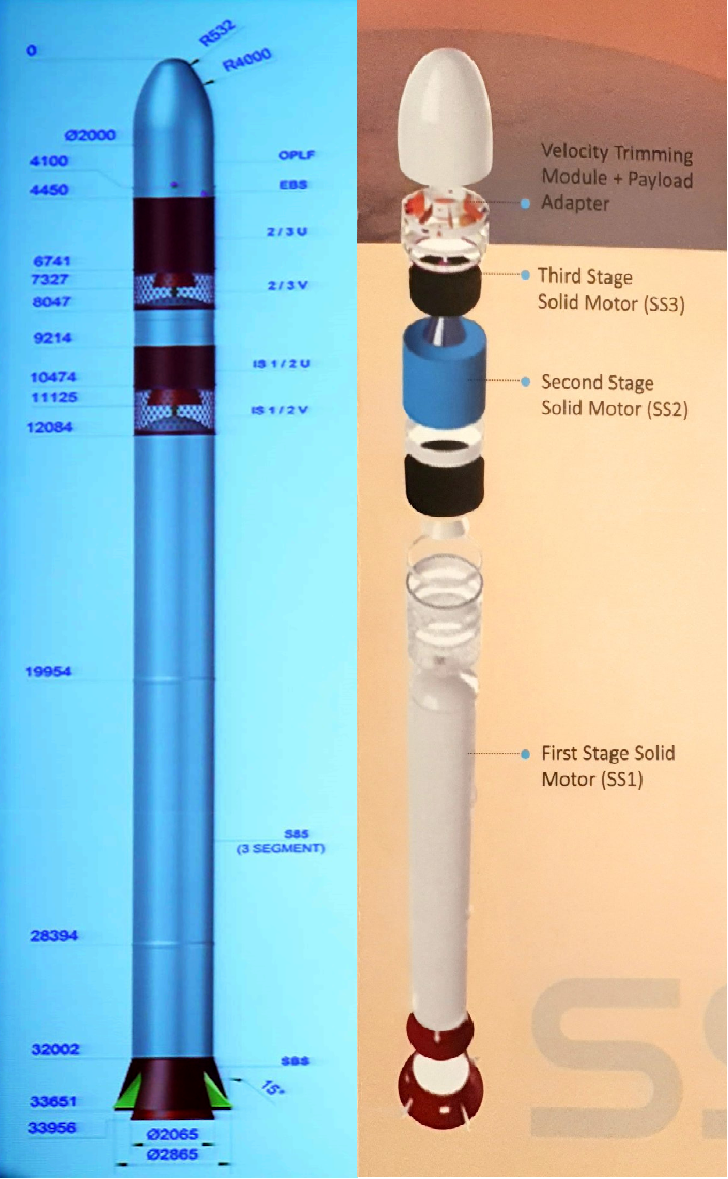

Diagrams from official SSLV Brochures

While ISRO’s focus has rightfully been on increasing the size & payload capacity of its rockets, it hasn’t forgotten the commercial & strategic implications of a small, launch-on-demand rocket system that can greatly reduce both the cost & lead team it generally takes to put a satellite into orbit – and neither has the Government of India forgotten the strategic implications of the same technology. In 2018 the agency completed preliminary design on its SSLV platform that aimed to fulfill this emerging requirement.

In the opinion of this author, the SSLV was formulated to support two sectors, an explicitly stated civilian use centered around the rocket’s reduced cost, and a so-far ambiguous military/strategic role centered around the rocket’s record quick assembly time & use of solid-fuel motors for all 3 of its stages (unlike similar sized small vehicles like RocketLab’s Electron which still use liquid engines).

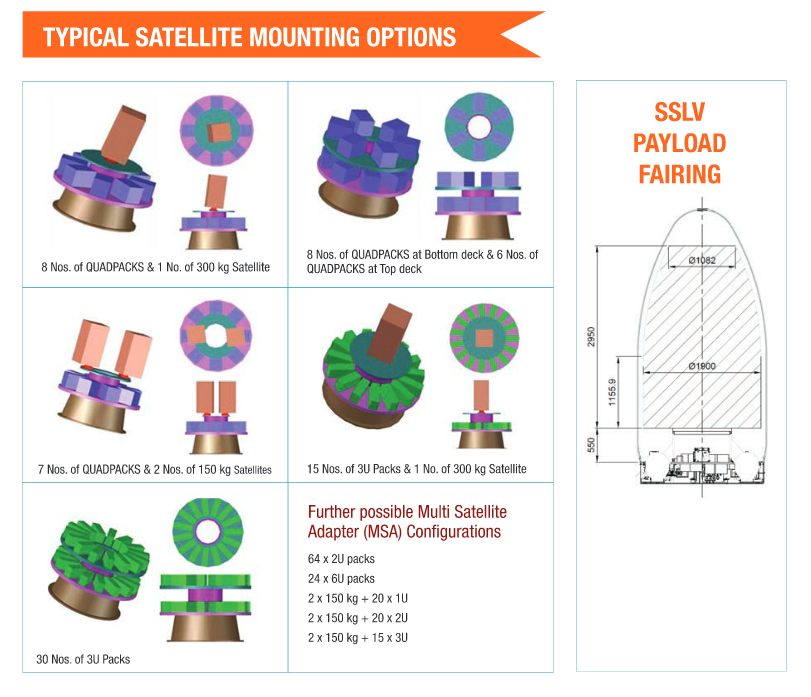

Various Satellite mounting options that the SSLV’s onboard Payload Adaptor can be configured for

Starting off with the civilian use-case; As the primary driving force behind the civilian launch market continues to be the cost factor, ISRO sought to reduce cost by maximizing technology commonality with the already proven PSLV & GSLV systems, considerably reducing the R&D cost for the new LV and allowing for a smaller margin to achieve profitability. Fine-tuning & streamlining the Private-sector production of components also enables the construction of affordable expendable stages. Adding to that, the reduction in infrastructure & human resources cost thanks to the strategic imperatives of this design (which we’ll go over in the next paragraph) also contributed to a planned sticker price per rocket of $4.2 million compared to $7.5 million for RocketLab’s Electron.

The largely ambiguous strategic use-case, rarely if ever talked about by either ISRO or Department of Space but inferred by this author to be the most pivotal role & effect of this launch vehicle, is one of supposition – a result of studying its design & configuration. The SSLV is designed to be highly modular, allowing for a full rocket to be assembled & readied for launch on just a 72-hour notice – down from the usual 60 days of notice it requires to assemble a large rocket like the PSLV (or the 16 days notice it takes to get a liquid-fueled small vehicle like the Electron ready for launch) – additionally, the Command & Control of the launch is designed to be managed by lightweight software from a single PC workstation. Whereas the PSLV took a workforce of 600 staff in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to put the rocket together, the small modular SSLV is designed to require only 6 people to complete its assembly, plus as per statements of the Chairman of ISRO, development of mobile launch solutions for the SSLV is also underway (offshore platform development confirmed, eventual use of land-mobile Transporter Erector Launcher (TEL) type vehicle for SSLV or some future version of it again inferred by the author). Similar in scope to the Chinese Long March-11 (offshore) & Kuaizhou-11 (road-mobile) rockets.

Assembly by a skeleton crew on short notice using modular components thanks to exclusion of liquid-fueled stages, C&C designed to accommodate field use without necessarily having access to extensive control facilities, or the ability to launch from austere conditions away from established launch pads all point toward a military-strategic nature of the system, very likely a requirement meant to be fulfilled by the newly formed Defence Space Agency (DSA), geared toward quickly re-establishing a limited satellite-based capability set on a short notice (to include navigation, earth observation, radar & infra-red reconnaissance, ELINT/SIGINT among other tactical uses) – in the event of existing long-term space assets being knocked out by an adversary’s ASAT weapons in a first-strike scenario.

The SSLV is currently undergoing static tests on its various stages & solid rocket motors, the first launch is expected sometime this year – it will be carrying the Microsat-2A payload (renamed to EOS-02 under the new broad-based ISRO naming scheme for satellites) on its first Demo flight.

NOTE: As with the preceding article, I will only be mentioning those programs that aim to develop a full-fledged orbital launch capability as their primary goal; as such programs like the Nano Satellite Launch Vehicle (NSLV) which in the opinion of this author are primarily aimed at a Sub-orbital launch capability, have been excluded.

Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV)

2021-2022

Diagrams from official SSLV Brochures

While ISRO’s focus has rightfully been on increasing the size & payload capacity of its rockets, it hasn’t forgotten the commercial & strategic implications of a small, launch-on-demand rocket system that can greatly reduce both the cost & lead team it generally takes to put a satellite into orbit – and neither has the Government of India forgotten the strategic implications of the same technology. In 2018 the agency completed preliminary design on its SSLV platform that aimed to fulfill this emerging requirement.

In the opinion of this author, the SSLV was formulated to support two sectors, an explicitly stated civilian use centered around the rocket’s reduced cost, and a so-far ambiguous military/strategic role centered around the rocket’s record quick assembly time & use of solid-fuel motors for all 3 of its stages (unlike similar sized small vehicles like RocketLab’s Electron which still use liquid engines).

Various Satellite mounting options that the SSLV’s onboard Payload Adaptor can be configured for

Starting off with the civilian use-case; As the primary driving force behind the civilian launch market continues to be the cost factor, ISRO sought to reduce cost by maximizing technology commonality with the already proven PSLV & GSLV systems, considerably reducing the R&D cost for the new LV and allowing for a smaller margin to achieve profitability. Fine-tuning & streamlining the Private-sector production of components also enables the construction of affordable expendable stages. Adding to that, the reduction in infrastructure & human resources cost thanks to the strategic imperatives of this design (which we’ll go over in the next paragraph) also contributed to a planned sticker price per rocket of $4.2 million compared to $7.5 million for RocketLab’s Electron.

The largely ambiguous strategic use-case, rarely if ever talked about by either ISRO or Department of Space but inferred by this author to be the most pivotal role & effect of this launch vehicle, is one of supposition – a result of studying its design & configuration. The SSLV is designed to be highly modular, allowing for a full rocket to be assembled & readied for launch on just a 72-hour notice – down from the usual 60 days of notice it requires to assemble a large rocket like the PSLV (or the 16 days notice it takes to get a liquid-fueled small vehicle like the Electron ready for launch) – additionally, the Command & Control of the launch is designed to be managed by lightweight software from a single PC workstation. Whereas the PSLV took a workforce of 600 staff in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to put the rocket together, the small modular SSLV is designed to require only 6 people to complete its assembly, plus as per statements of the Chairman of ISRO, development of mobile launch solutions for the SSLV is also underway (offshore platform development confirmed, eventual use of land-mobile Transporter Erector Launcher (TEL) type vehicle for SSLV or some future version of it again inferred by the author). Similar in scope to the Chinese Long March-11 (offshore) & Kuaizhou-11 (road-mobile) rockets.

Assembly by a skeleton crew on short notice using modular components thanks to exclusion of liquid-fueled stages, C&C designed to accommodate field use without necessarily having access to extensive control facilities, or the ability to launch from austere conditions away from established launch pads all point toward a military-strategic nature of the system, very likely a requirement meant to be fulfilled by the newly formed Defence Space Agency (DSA), geared toward quickly re-establishing a limited satellite-based capability set on a short notice (to include navigation, earth observation, radar & infra-red reconnaissance, ELINT/SIGINT among other tactical uses) – in the event of existing long-term space assets being knocked out by an adversary’s ASAT weapons in a first-strike scenario.

The SSLV is currently undergoing static tests on its various stages & solid rocket motors, the first launch is expected sometime this year – it will be carrying the Microsat-2A payload (renamed to EOS-02 under the new broad-based ISRO naming scheme for satellites) on its first Demo flight.

Status: Static Stage Testing

Liftoff mass: 120 tons | Height: 34m | Payload to LEO: 500kg | Payload to SSO: 300kg

Intended Objectives

Affordable access to space for smaller & lighter payloads, supported by more frequent launches | Possible strategic use as a means of re-establishing critical space-based services in the event of hostile Anti-Satellite action

===================

Advanced Mission & Recovery Experiments (ADMIRE)

2021-2025

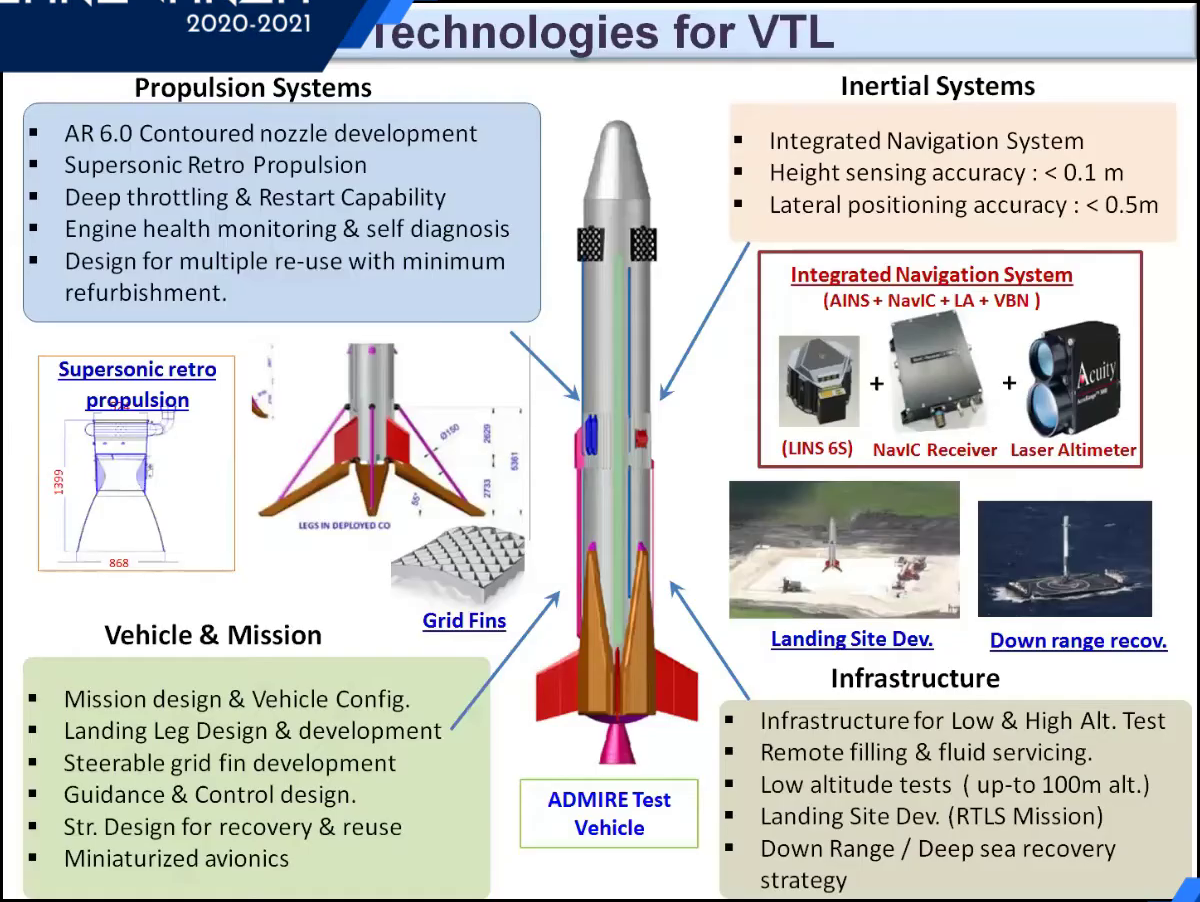

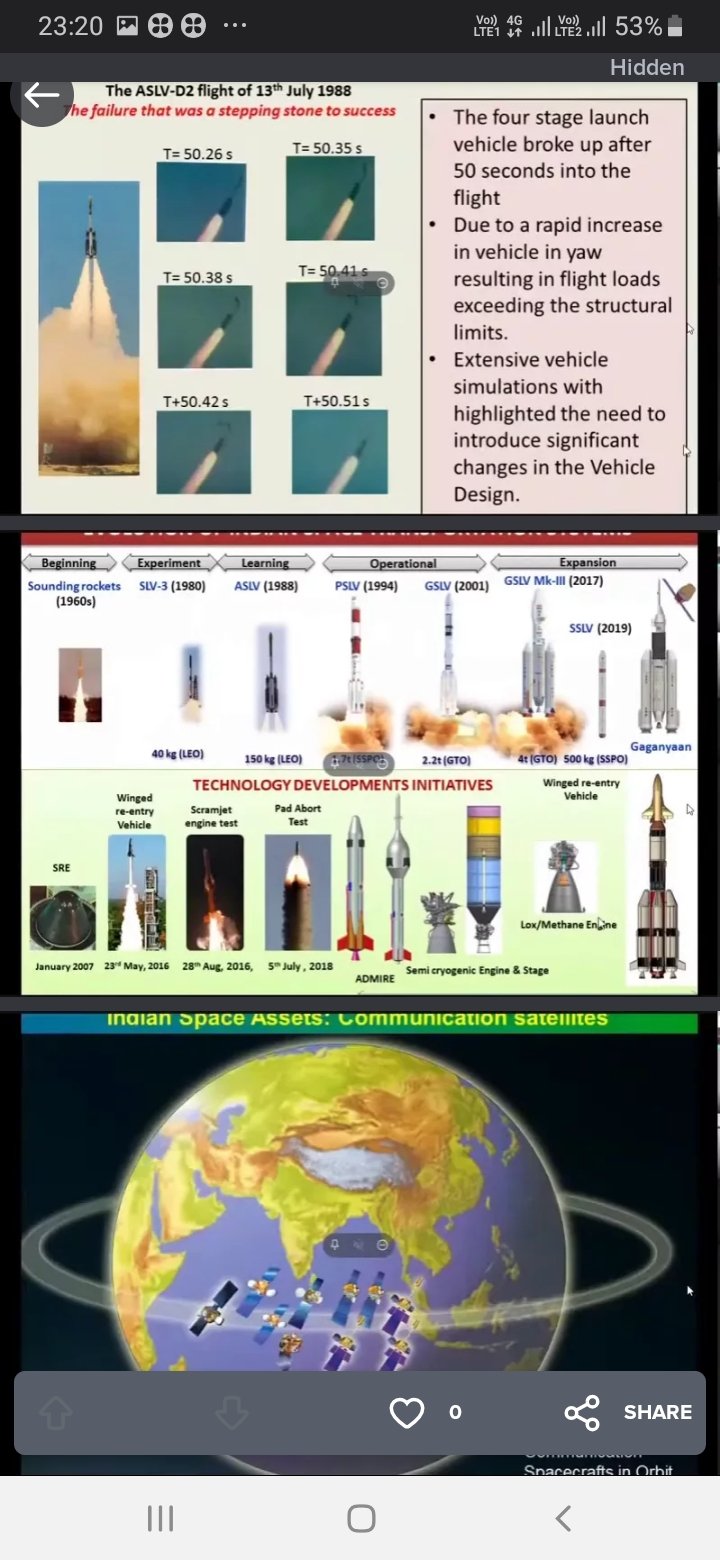

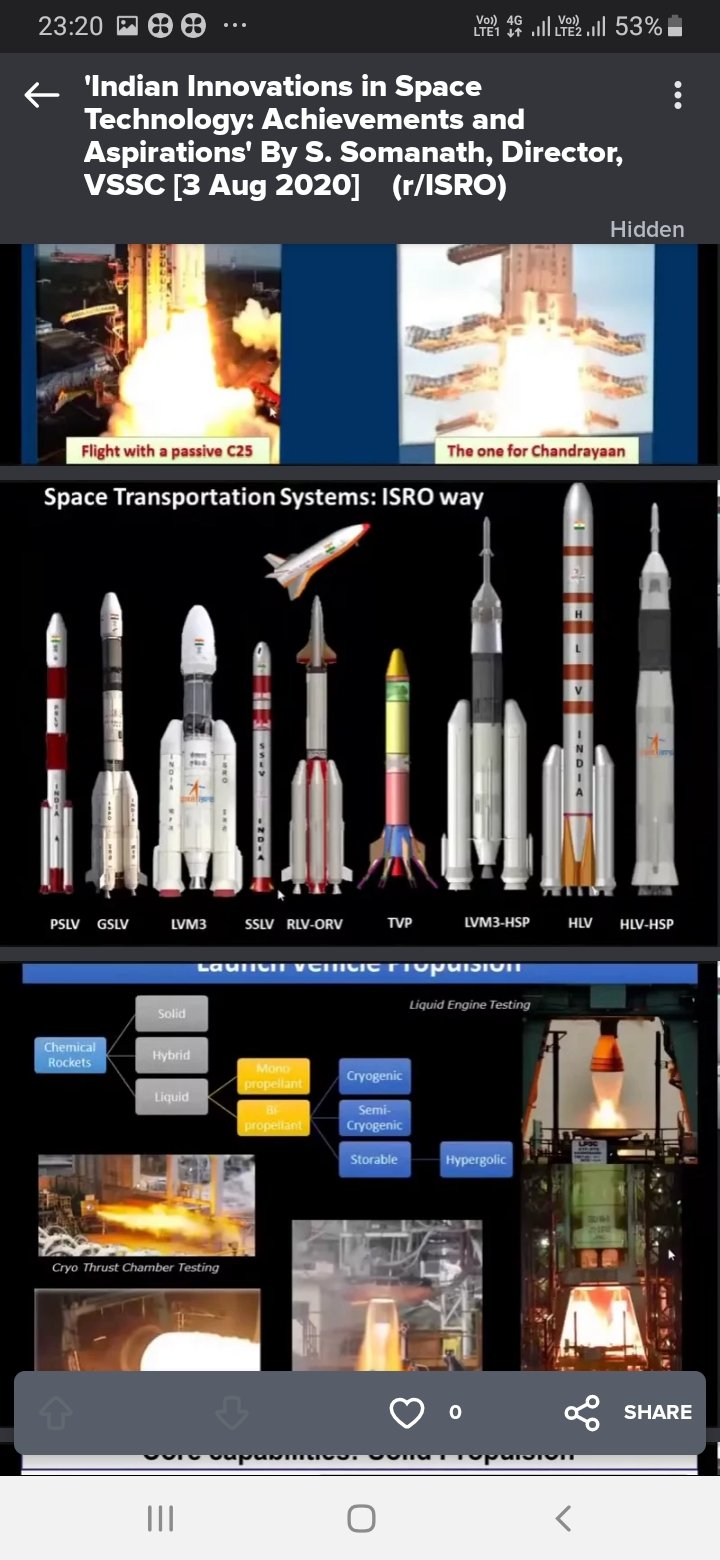

From a presentation by Dr. S. Somanath of Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC), detailing various technologies being developed to support the reusable stage program

While its chief R&D activities continue to be on the front of next-gen propulsion systems for both rockets & hypersonic spaceplanes, as it should considering the fact it remains a state-run enterprise, ISRO isn’t blind to the advantages of re-usable vertical takeoff & vertical landing (VTVL) rockets à la SpaceX Falcon 9 and the value they bring to the commercial launch market – and the need to develop similar technologies for Indian launchers. The ADMIRE program aims to do just that: Development, demonstration & eventual commercialization of a liquid-fueled booster stage that can take off vertically like a normal rocket, and after separation, autonomously guide itself back to a designated LZ and land under its own power.

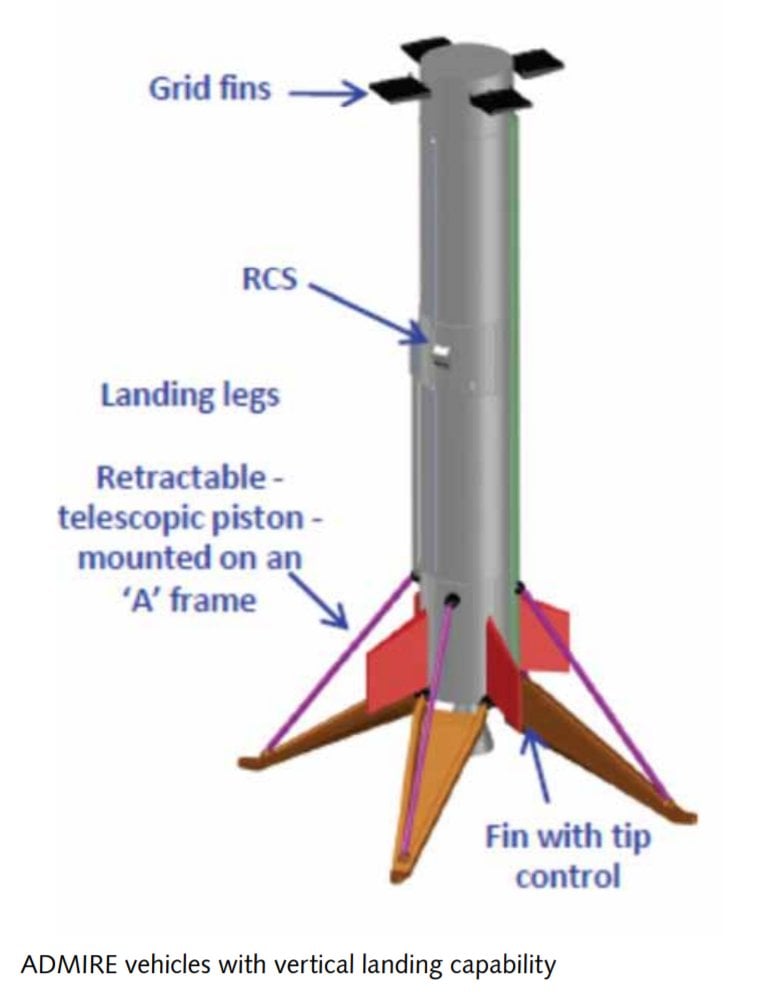

ADMIRE booster with its landing legs deployed

While the initial ADMIRE boosters themselves will be small, the focus will be on the software end, on developing the guidance & sensor package that will allow creation of a VTVL booster. The technology will then be scaled up and potentially applied to all liquid-fueled ISRO rockets performing commercial launch operations – incurring further cost reductions that way.

Advanced Mission & Recovery Experiments (ADMIRE)

2021-2025

From a presentation by Dr. S. Somanath of Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC), detailing various technologies being developed to support the reusable stage program

While its chief R&D activities continue to be on the front of next-gen propulsion systems for both rockets & hypersonic spaceplanes, as it should considering the fact it remains a state-run enterprise, ISRO isn’t blind to the advantages of re-usable vertical takeoff & vertical landing (VTVL) rockets à la SpaceX Falcon 9 and the value they bring to the commercial launch market – and the need to develop similar technologies for Indian launchers. The ADMIRE program aims to do just that: Development, demonstration & eventual commercialization of a liquid-fueled booster stage that can take off vertically like a normal rocket, and after separation, autonomously guide itself back to a designated LZ and land under its own power.

ADMIRE booster with its landing legs deployed

While the initial ADMIRE boosters themselves will be small, the focus will be on the software end, on developing the guidance & sensor package that will allow creation of a VTVL booster. The technology will then be scaled up and potentially applied to all liquid-fueled ISRO rockets performing commercial launch operations – incurring further cost reductions that way.

Status: Advanced Design & Back-end Development Stage

Intended Objectives

Developing technologies to support increased affordability of repeated space launches by recovering & re-using the boost stages

===================

Private-sector Launchers

2022

Artist render of Skyroot Aerospace’s Vikram-I Launch Vehicle

Since around 2015, several private-sector start-ups have sought a piece of the multi-billion space industry pie by focusing on various niche technology fields such as in-space satellite propulsion, satellite-based services, and more recently following liberalization of the laws & regulations surrounding the space sector in 2019, privately-developed launch vehicles.

For the purposes of this article, I’m going to be focusing on three of the more prominent private companies currently engaged in some form of launch vehicle or related technology development. Namely Skyroot Aerospace, Agnikul Cosmos & Bellatrix Aerospace.

Skyroot, founded by a group of ex-ISRO scientists & funded to the tune of $15 million by several Indian & foreign investors and with the support of several top ISRO personnel in advisory positions is currently the best-placed organization to develop a private-sector launch capability in the form of their Vikram-series of small satellite launchers.

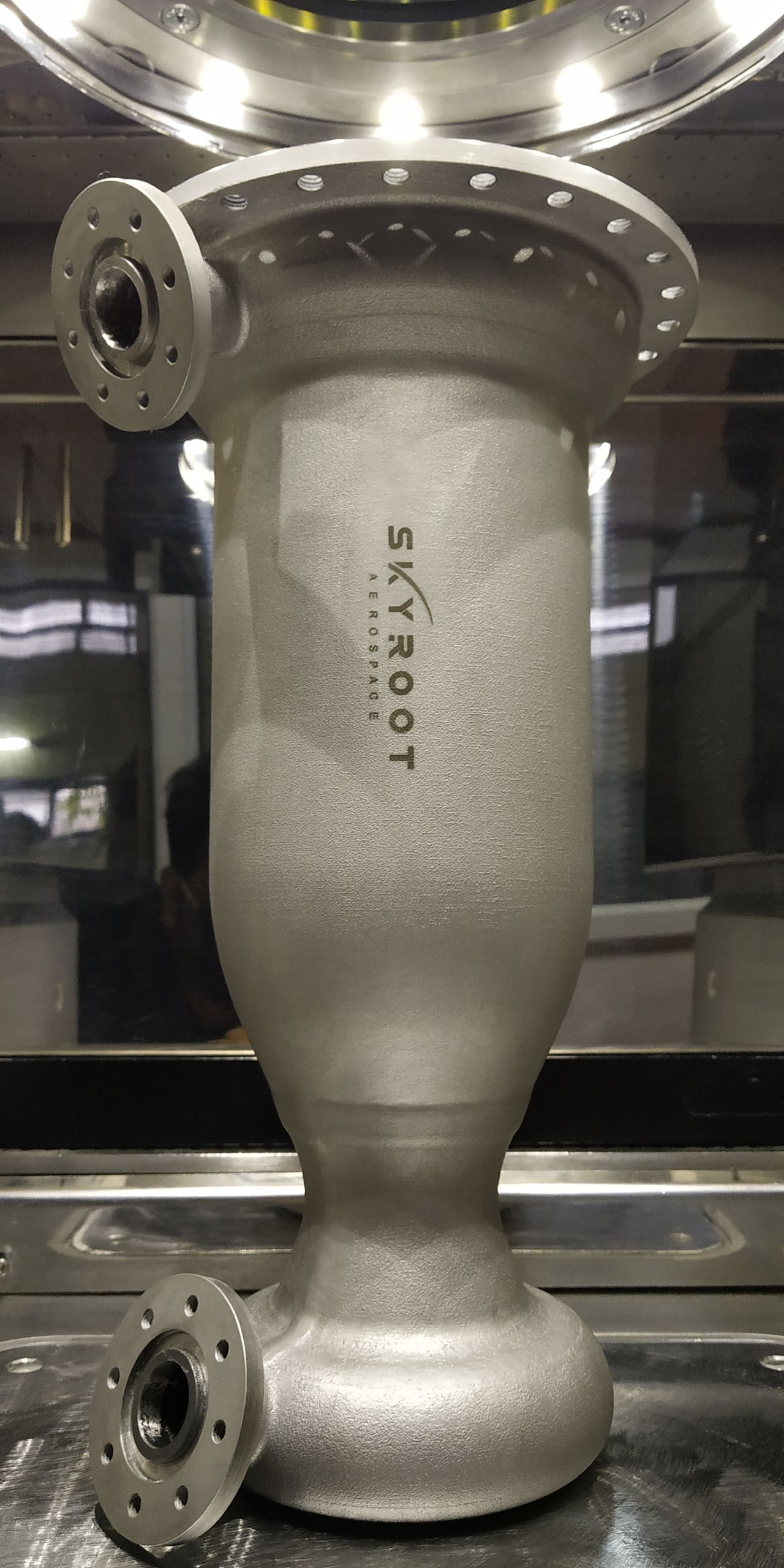

Skyroot Aerospace 3D-printed Dhawan-1 cryogenic engine

Vikram-I, the first in line to be developed is intended to have a payload capacity of 315kg to LEO & 225kg to SSPO – in the same overall payload class as the RocketLab Electron. But with all-solid propulsion, 3D-printed components & modular design, Skyroot is aiming for a 24-hour assembly period (making it a potential pitch for the DSA as well). This will be followed by the Vikram-II with a Cryogenic Methalox upper stage boosting the payload capacity to 520kg LEO/410kg SSPO, and finally the Vikram-III with the same Cryo engine supported by additional solid rocket boosters in the first stage, taking payloads to 720kg LEO/580kg SSPO.

Agnikul’s Agnilet 3D-printed liquid engine

Skyroot test-fired their Raman liquid-fueled Orbital Adjustment Module (for velocity-trimming of the payload section) in August 2020, followed by the Kalam-5 solid rocket motor in December 2020, and the LNG/LoX-fueled Dhawan-1 cryogenic engine was also unveiled that same year. The cryo stage intended for Vikram-II & III will allow for multi-orbit placement of satellite payloads. Skyroot expects the first launch of Vikram-I sometime in 2022.

Agnibaan by Agnikul Cosmos

Agnikul Cosmos, a startup incubated at the IIT-Madras university’s NCCRD (National Centre for Combustion Research & Development) and backed by $11 million in Series-A funding is focusing on smaller liquid-fueled rockets. Their 2/3-stage (depending on configuration) Agnibaan rocket is designed to have a LEO payload capacity of 100kg. In February 2021, their Kerolox-fueled Agnilet semi-cryogenic 2nd stage motor was test fired. This will be followed by tests of the Agnite first-stage motor sometime this year. The Agnibaan’s first stage will comprise of 7 clustered Agnite engines each producing 25kN of thrust. Angikul is also aiming for full road-mobility of the rocket’s carrier vehicle. First launch of this system is also expected in 2022.

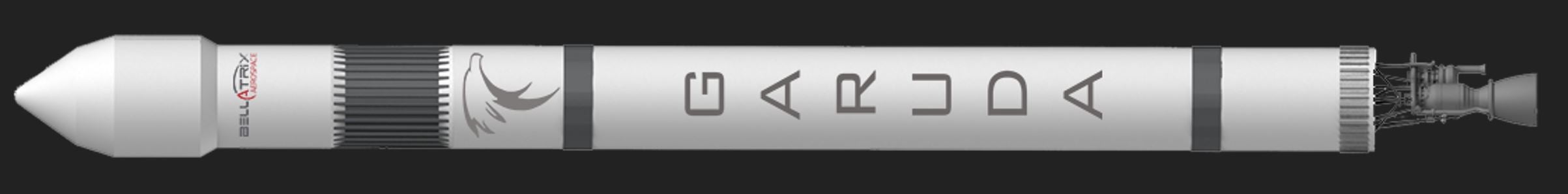

Bellatrix Garuda

Which brings us to Bellatrix – a startup primarily focused on in-space satellite propulsion with their May 2021 test of India’s first privately-developed Hall-effect thruster, and which also deserves a mention in this list. Although they do have plans for launch vehicles of their own – namely the 12-ton 150kg SSO Chetak and 43-ton 1,000kg SSO Garuda, their focus for the immediate future remains development of the Bellatrix Aerospace Orbital Transportation Vehicle (OTV) – now named Pushpak, a ‘space taxi’ similar in profile to the American Momentus Vigoride. The OTV is powered by 4 x 200W Hall thrusters and allows for even smaller launch vehicles to send payloads into Geostationary orbits by providing continuous propulsion in space long after the rocket itself is spent. The OTV has been contracted by Skyroot Aerospace to be used on their Vikram-series launchers.

CGI of Bellatrix Aerospace OTV (Orbital Transportation Vehicle) made by Youtuber Gareeb Scientist

Both Skyroot & Agnikul are currently targeting the small launch vehicle sector as that’s the area with the most clear-cut way to profitability at this stage and with their current levels of investment.

Private-sector Launchers

2022

Artist render of Skyroot Aerospace’s Vikram-I Launch Vehicle

Since around 2015, several private-sector start-ups have sought a piece of the multi-billion space industry pie by focusing on various niche technology fields such as in-space satellite propulsion, satellite-based services, and more recently following liberalization of the laws & regulations surrounding the space sector in 2019, privately-developed launch vehicles.

For the purposes of this article, I’m going to be focusing on three of the more prominent private companies currently engaged in some form of launch vehicle or related technology development. Namely Skyroot Aerospace, Agnikul Cosmos & Bellatrix Aerospace.

Skyroot, founded by a group of ex-ISRO scientists & funded to the tune of $15 million by several Indian & foreign investors and with the support of several top ISRO personnel in advisory positions is currently the best-placed organization to develop a private-sector launch capability in the form of their Vikram-series of small satellite launchers.

Skyroot Aerospace 3D-printed Dhawan-1 cryogenic engine

Vikram-I, the first in line to be developed is intended to have a payload capacity of 315kg to LEO & 225kg to SSPO – in the same overall payload class as the RocketLab Electron. But with all-solid propulsion, 3D-printed components & modular design, Skyroot is aiming for a 24-hour assembly period (making it a potential pitch for the DSA as well). This will be followed by the Vikram-II with a Cryogenic Methalox upper stage boosting the payload capacity to 520kg LEO/410kg SSPO, and finally the Vikram-III with the same Cryo engine supported by additional solid rocket boosters in the first stage, taking payloads to 720kg LEO/580kg SSPO.

Agnikul’s Agnilet 3D-printed liquid engine

Skyroot test-fired their Raman liquid-fueled Orbital Adjustment Module (for velocity-trimming of the payload section) in August 2020, followed by the Kalam-5 solid rocket motor in December 2020, and the LNG/LoX-fueled Dhawan-1 cryogenic engine was also unveiled that same year. The cryo stage intended for Vikram-II & III will allow for multi-orbit placement of satellite payloads. Skyroot expects the first launch of Vikram-I sometime in 2022.

Agnibaan by Agnikul Cosmos

Agnikul Cosmos, a startup incubated at the IIT-Madras university’s NCCRD (National Centre for Combustion Research & Development) and backed by $11 million in Series-A funding is focusing on smaller liquid-fueled rockets. Their 2/3-stage (depending on configuration) Agnibaan rocket is designed to have a LEO payload capacity of 100kg. In February 2021, their Kerolox-fueled Agnilet semi-cryogenic 2nd stage motor was test fired. This will be followed by tests of the Agnite first-stage motor sometime this year. The Agnibaan’s first stage will comprise of 7 clustered Agnite engines each producing 25kN of thrust. Angikul is also aiming for full road-mobility of the rocket’s carrier vehicle. First launch of this system is also expected in 2022.

Bellatrix Garuda

Which brings us to Bellatrix – a startup primarily focused on in-space satellite propulsion with their May 2021 test of India’s first privately-developed Hall-effect thruster, and which also deserves a mention in this list. Although they do have plans for launch vehicles of their own – namely the 12-ton 150kg SSO Chetak and 43-ton 1,000kg SSO Garuda, their focus for the immediate future remains development of the Bellatrix Aerospace Orbital Transportation Vehicle (OTV) – now named Pushpak, a ‘space taxi’ similar in profile to the American Momentus Vigoride. The OTV is powered by 4 x 200W Hall thrusters and allows for even smaller launch vehicles to send payloads into Geostationary orbits by providing continuous propulsion in space long after the rocket itself is spent. The OTV has been contracted by Skyroot Aerospace to be used on their Vikram-series launchers.

CGI of Bellatrix Aerospace OTV (Orbital Transportation Vehicle) made by Youtuber Gareeb Scientist

Both Skyroot & Agnikul are currently targeting the small launch vehicle sector as that’s the area with the most clear-cut way to profitability at this stage and with their current levels of investment.

Vikram-series

Liftoff mass & Height unknown | Payload to LEO: 315-720kg | Payload to SSO/SSPO: 225-580kg

Angibaan

Liftoff mass: 14 tons | Height: 18m | Payload to LEO: 100kg

Status of both: Stages Under Development

Intended Objectives

Low-cost access to space for micro & small satellite payloads | Development of end-to-end Private sector aerospace ecosystem

===================

Continued...

Continued...

only question is when this will be built

only question is when this will be built